Texas detections point to wild migratory birds as source; Public risk remains low; Cows exhibit low appetite, reduced rumination, sharply reduced milk production

By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, March 29, 2024 (updated since print edition went to press)

WASHINGTON – Federal and state officials confirmed this week that highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), otherwise known as bird flu, has been detected and deemed the culprit in the mystery illness “among primarily older (mid-lactation) dairy cows in Texas, Kansas, and New Mexico that is causing decreased lactation, low appetite, and other symptoms.”

USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) believes “wild migratory birds to be the source of infection as viral testing and epidemiological efforts continue.”

In an email exchange with the APHIS press office on Wed., March 27, Farmshine asked if cow-to-cow transmission has been ruled out at this juncture.

They could not answer directly, but on background, gave this response that mirrored a portion of the March 25 APHIS press release:

“The testing from Texas shows consistency with the strain seen in wild birds. As the release shared, based on the findings, the detections in Texas appear to have been introduced by wild birds. Federal and state agencies are moving quickly to conduct additional testing for HPAI, as well as viral genome sequencing, so that we can better understand the situation, including characterization of the HPAI strain or strains associated with these detections.”

The answer appears to be that cow-to-cow transmission is not suspected as birds are the vector in what APHIS describes as a “rapidly evolving situation” and one in which they are continuing to investigate, working closely with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as well as state veterinary and public health officials.

Furthermore, if migratory wild birds are the source, then this could be a seasonal anomaly that may shift or dissipate soon.

Word spread quickly on Monday, March 25 as public announcements from federal and state agencies and industry organizations were released in rapid, near simultaneous succession within minutes of the USDA APHIS press release announcing that, “Unpasteurized, clinical samples of milk from sick cattle collected from two dairy farms in Kansas and one in Texas, as well as an oropharyngeal swab from another dairy in Texas have all tested positive for HPAI. Additional testing was initiated on Friday, March 22, and over the weekend, because farms have also reported finding deceased wild birds on their properties.”

Preliminary testing by the National Veterinary Services Laboratories further confirmed that, “No changes to the virus have been found that would make it more transmissible to humans, which would indicate that the current risk to the public remains low.”

Announcements from all corners of health and industry conveyed this main message: “At this stage, there is no concern about the safety of the commercial milk supply or that this circumstance poses a risk to consumer health. The commercial milk supply remains safe due to both federal animal health requirements and pasteurization.”

Bird flu (avian influenza) is a disease caused by a family of flu viruses primarily transmitted among birds.

According to USDA, there are two classifications, and the ‘high’ or ‘low’ pathogenic acronyms are based on the genetic sequence and the severity of disease caused in poultry: HPAI (high pathogenic, meaning it causes severe disease in poultry), which is found mostly in domestic poultry and LPAI (low pathogenic, meaning it causes no signs or few signs of disease in poultry), which is often seen in wild birds.

“It is too soon to predict if all of the recent reports of unexplained illnesses in dairy cattle in the U.S. are due to HPAI. Veterinarians and the dairy industry are working collaboratively with state and federal officials during the ongoing investigation,” noted the American Association of Bovine Practitioners in a March 25 press release

AABP reports that HPAI (H5N1) is most commonly found in birds and poultry with wild waterfowl as known carriers. According to the USDA, 48 states have had cases of HPAI in poultry and wild birds since the outbreak began in 2022. Over 82 million birds have been affected. There have also been reports of over 200 mammals diagnosed with the virus.

The samples from Texas and Kansas are the first confirmed detections of HPAI (H5N1) in cattle anywhere in the U.S. and only the second mammalian detection in Texas, the first being a skunk.

This marks the second detection in a ruminant animal in the U.S. The first was just a week prior, when HPAI was detected in a goat on a Minnesota farm where chickens and ducks had been quarantined for previous HPAI detection.

In a March 26 American Veterinary Medical Association newsletter, Dr. Brian Hoefs, Minnesota state veterinarian, noted that, “Thankfully, research to-date has shown mammals appear to be dead-end hosts, which means they’re unlikely to spread HPAI further.”

“Mammals, including cows, do not spread avian influenza — it requires birds as the vector of transmission, and it’s extremely rare for the virus to affect humans because most people will never have direct and prolonged contact with an infected bird, especially on a dairy farm,” a joint dairy industry statement by National Milk Producers Federation (NMPF), International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA), Dairy Management Inc (DMI), and U.S. Dairy Export Council (USDEC) reported on March 25.

Since early 2022, when HPAI was first confirmed in wild waterfowl in the Atlantic flyways and the first domestic poultry flocks were affected, APHIS has been tracking wild mammal detections in the U.S. The list includes skunks, racoon, red and gray fox, coyote, several types of bears, mountain lions, bobcats, fishers, opossums, martens, and harbor seals – all having in common their known contact with wild waterfowl and/or domestic poultry and/or their eggs.

The APHIS webpage devoted to avian influenza notes that, “Wild birds can be infected with HPAI and still show no signs of illness. They can carry the disease to new areas when migrating, potentially exposing domestic poultry to the virus.”

This is why APHIS conducts a wild bird surveillance program to provide early warning system for the introduction and distribution of avian influenza viruses of concern in the U.S., allowing APHIS and the poultry industry to take timely and rapid action to reduce the risk of spread to the poultry industry and other populations of concern.

For the U.S. poultry industry, HPAI detection in domestic flocks means implementing response programs for flock depopulation and geographic quarantine to prevent the spread because of the high mortality rate in domestic poultry and bird-to-bird transmission within a production setting. According to USDA, approximately 58 million birds were killed in such depopulations in the U.S. last year.

The current detection in cattle is different because there is no confirmation of cow-to-cow transmission, and according to AABP, “there have been no confirmed deaths in cattle due to this disease. Cattle appear to recover in two to three weeks with supportive care.”

“Unlike affected poultry, I foresee there will be no need to depopulate dairy herds. Cattle are expected to fully recover,” said Texas Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller in a press statement March 25, noting that the Texas dairy industry contributes roughly $50 billion in state economic activity, ranking 4th in milk production nationwide in 2023, moving up to 3rd since the start of 2024.

Assuring consumers of rigorous safety measures already in place and soothing concerns about potential milk supply shortages, Commissioner Miller highlighted pasteurization and milk diversion protocols and the “limited number of affected herds.”

The required dumping of abnormal-appearing milk or milk from sick cows, as well as pasteurization as a fail-safe inactivation of bacterial and viral agents were stressed in the variety of press releases as normal public health safeguards already in place.

“There is no threat to the public, and there will be no supply shortages,” assured Commissioner Miller. “No contaminated milk is known to have entered the food chain; it has all been dumped. In the rare event that some affected milk enters the food chain, the pasteurization process will kill the virus.”

He also noted that, “Cattle impacted by HPAI exhibit flu-like symptoms including fever and a sharp reduction in milk production averaging between 10-30 pounds per cow throughout the herd.”

“On average about 10% of each affected herd appears to be impacted, with little to no associated mortality reported among the animals,” the USDA APHIS report stated, with declines in milk production described as “too limited to impact the supply and price of milk and dairy products.”

Yet in an AABP webinar March 22, before the HPAI strain was confirmed in the Texas and Kansas samples, the findings of veterinarians involved early-on over the past four to six weeks were described, and presenters were asked about the numbers of affected dairy cattle.

An effort is underway “to count them up, but the number is significant, and I’ll leave it at that,” said Dr. Brandon Treichler, DVM, who was joined by Dr. Alexis Thompson with Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory (TVMDL) in presenting AABP webinar information.

Treichler hails from a family dairy farm in eastern Pennsylvania and serves as a quality control veterinarian, primarily working with large dairies in West Texas and eastern New Mexico. He is active with AABP and National Mastitis Council.

Previously mentioned are the higher rates of culling in herds where an economic decision is made about affected cattle in mid-lactation, when their production is not regained after recovering to health.

Dr. Treichler talked about practitioner findings as “inclusion criteria,” and mentioned some herd to herd variations as well.

“The most consistent factors seen across herds include a decreased feed intake in the herd and at the same time less rumination… These cows are being sorted for us for changes in the milk, and (the facilities that have) conductivity available will see conductivity spike on a large number of cows, and then decreasing milk production across the herd, with individual cows seemingly more severely affected, going from a high production cow to dry or very nearly dry, very quickly. Some of those cows appear to have colostrum-like milk that is either thickened, or thickened with some discoloration,” he said.

According to Treichler, manure among the more severely affected cows is reported to range from dry or tacky to some diarrhea. Other signs that vary include fever, which is potentially attributable to the impact on the immune system from the metabolic disruption of being off-feed with reduced rumination.

In his March 25 press statement, Texas Ag Commissioner Miller cited “ongoing economic impacts to facilities as herds that are greatly impacted may lose up to 40% of their milk production for 7 to 10 days until symptoms subside. It is vital that dairy facilities nationwide practice heightened biosecurity measures to mitigate further spread.”

He advised dairies in the region “to use all standard biosecurity measures, including restricting access to essential personnel only, disinfecting all vehicles entering and leaving premises, isolating affected cattle, and destroying all contaminated milk. Additionally, it is important to clean and disinfect all livestock watering devices and isolate drinking water where it might be contaminated by waterfowl.”

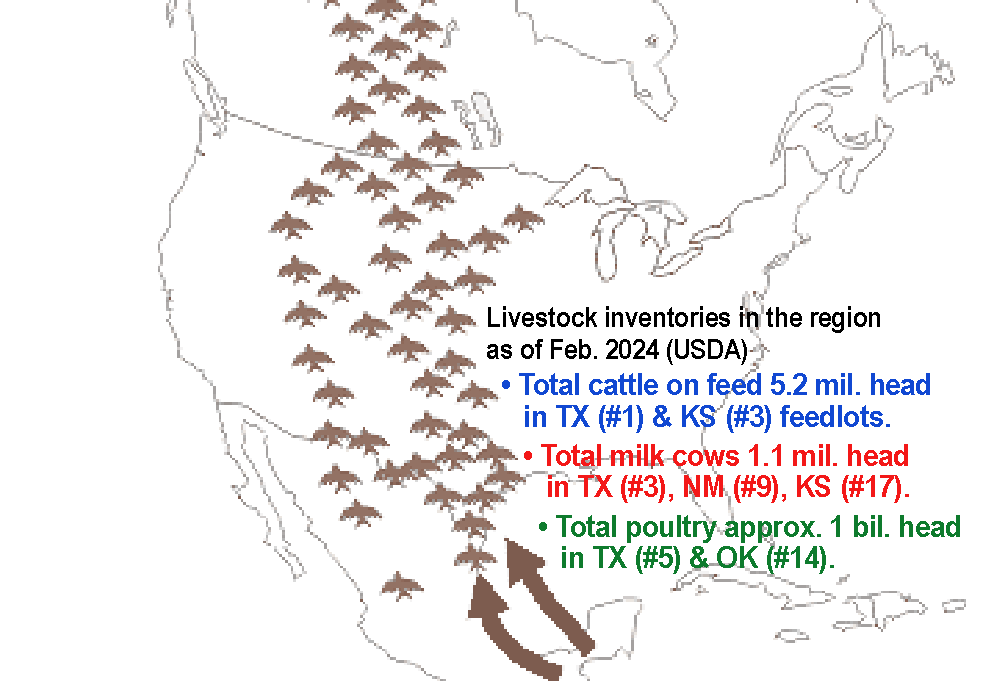

No affected beef cattle have been reported, only older primarily mid-lactation dairy cows. This is interesting, considering the fact that the number of cattle on feed — mostly in open lots similar to drylot dairies that are prevalent in the Panhandle region of the No. 1 cattle feeding state of Texas and No. 3 Kansas – far outweigh milk cow numbers by 5 to 1.

The region’s milk cows are most concentrated in and around the Panhandle of the No. 3 dairy state of Texas, No. 9 New Mexico and No. 17 Kansas portions of the Central Flyway for ‘migratory wild birds.’

Also within this zone are the country’s 5th and 14th largest poultry states of Texas and Oklahoma, respectively, totaling a combined nearly 1 billion head of poultry.

Farmshine asked APHIS and the Texas Animal Health Commission (TAHC) about the status of beef cattle monitoring, to which a TAHC spokesperson responded by email noting: “TAHC and Texas A&M TVMDL have, and continue to ask for, samples from affected and unaffected dairies to gather the full scope of the situation. The feedlot and beef cattle industry are monitoring and doing similar surveillance among their producers that many dairy operations have been conducting — not specifically screening, necessarily, but many are watching for clinical signs of illness that they can identify in the operation and keeping a close eye for abnormal health events among their herds.”

On other questions about whether there are any differences or commonalities in terms of external contributing factors among affected herds, the TAHC spokesperson stated “No dairy specific information could be provided related to type of facilities or other factors where HPAI was detected.”

Dairy industry organization statements point to the National Dairy Producer FARM Program (NDPFP) as the go-to for specific biosecurity, reporting, and recordkeeping measures that are urged on all U.S. dairy farms, including much emphasis being given to the safeguard of milk pasteurization.

“Dairy farmers have begun implementing enhanced biosecurity protocols on their farms, limiting the amount of traffic into and out of their properties and restricting visits to employees and essential personnel,” the NMPF-IDFA-DMI-USDEC joint statement noted.

They cite biosecurity resources, including reference manuals, prep guides, herd health plan protocol templates, animal movement logs, and people entry logs that dairies can use “to keep their cattle and dairy businesses safe.”

USDA APHIS encourages farmers and veterinarians, nationwide, to report cattle illnesses quickly so they can “monitor potential additional cases and minimize the impact to farmers, consumers and other animals.”

Industry announcements urge dairy farmers to immediately contact their veterinarians if they observe clinical signs in their herds that are consistent with this outbreak, such as a significant loss of animal appetite and rumination or an acute drop in milk production.

In turn, veterinarians who observe these clinical signs and have ruled out other diagnoses on a client’s farm should contact the state veterinarian and plan to submit a complete set of samples to be tested at a diagnostic laboratory.

Animals may also be reported to the APHIS toll-free number at 1-866-536-7593.

In Pennsylvania, where HPAI depopulations and quarantines have occurred over the past two years in the poultry industry, there have been no reported cattle affected. However, the state is monitoring the situation, and the Center for Dairy Excellence is conducting a conference call by zoom and telephone at Noon EDT on Wed., April 3 for dairy producers and dairy industry service providers, featuring state veterinarian Dr. Alex Hamberg and Penn State extension vet Dr. Hayley Springer.

-30-

Pingback: ‘Bird flu’ expands to 13 dairy herds in 6 states | Ag Moos

Pingback: Pa. orders dairy cattle movement restrictions, testing to protect against HPAI spread; detections now in 8 states | Ag Moos