CDC confirms one worker in Texas recovered with mild symptoms; Cow-to-cow transmission ‘cannot be ruled out’, biosecurity paramount

By Sherry Bunting, for Farmshine’s April 5, 2024 edition

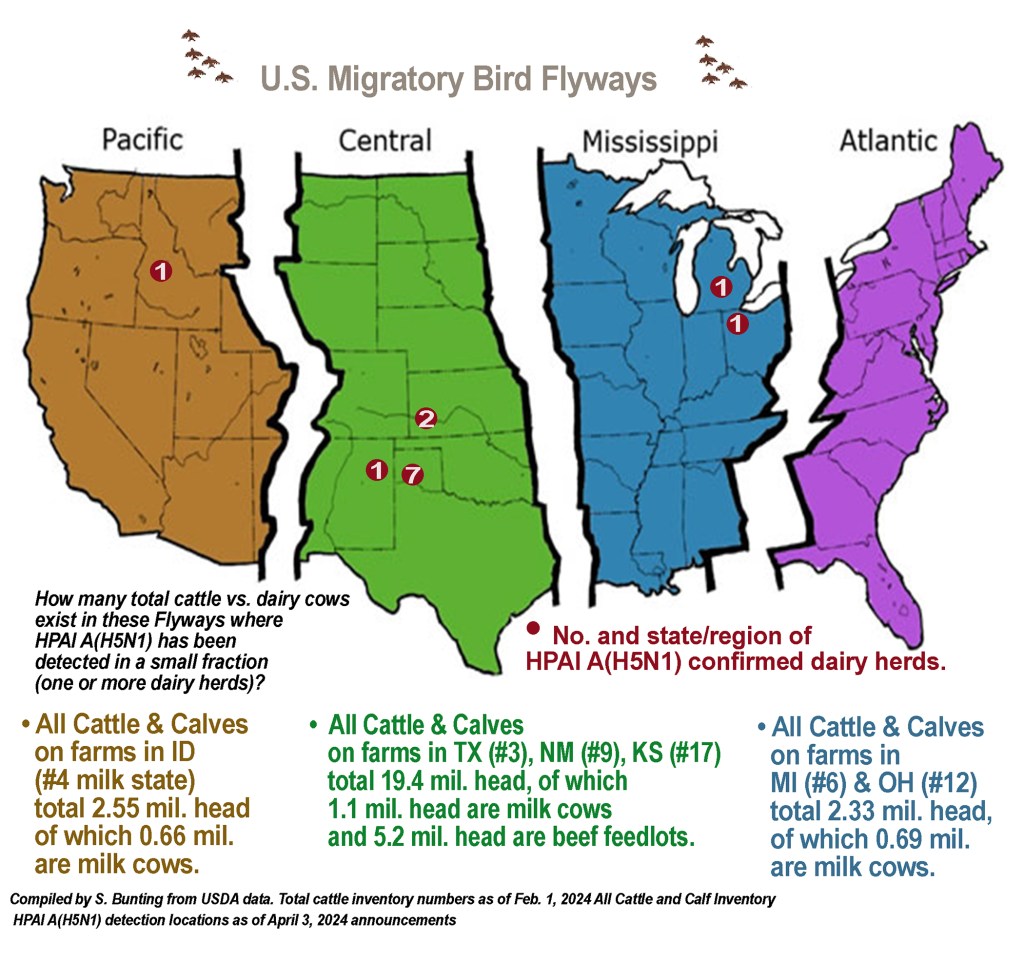

WASHINGTON — Detections of highly pathogenic avian influenza in dairy cows — HPAI A(H5N1) — have expanded to 13 herds in 6 states as of Wednesday, April 3: Texas (7), Kansas (2), Michigan (1), New Mexico (1), Idaho (1), and Ohio (1).

Some states, including but not limited to Nebraska, Idaho and Utah have begun issuing import permit requirements for cattle and/or restrictions on non-terminal and/or breeding cattle coming from specific areas. These instructions are available from state authorities, not USDA APHIS.

USDA’s APHIS has a new landing page for daily updates and other resources at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections/livestock

In addition, the CDC reported April 1 that a worker on a Texas Panhandle dairy, where HPAI was detected, has tested positive with mild flu symptoms, mainly conjunctivitis (pinkeye), and has recovered. The only other human case in the U.S. was a poultry farm worker in Colorado in 2022.

According to the CDC, their “human health risk assessment for the general public remains low. There continues to be no concern that this circumstance poses a risk to consumer health, or that it affects the safety of the commercial milk supply because products are pasteurized before entering the market,” and milk from infected animals is to be discarded.

New detections of the virus have not changed the primary belief that HPAI A(H5N1) is ‘seeded’ by migratory wild birds (emphasis on waterfowl and by association, vultures).

Cow-to-cow transmission questioned

Complicating the question of potential cow-to-cow transmission, it was reported that the two confirmed herds in Idaho and Michigan had recently received cattle from other states where HPAI A(H5N1) was detected.

APHIS officials stated on March 29 that, “Spread of symptoms among the Michigan herd also indicates that HPAI transmission between cattle cannot be ruled out; USDA and partners continue to monitor this closely and have advised veterinarians and producers to practice good biosecurity.”

During the April 3 Center for Dairy Excellence (CDE) industry call attended virtually by 189 people – the first such call to occur weekly on Wednesdays at Noon – the Pennsylvania State Veterinarian Dr. Alex Hamberg was asked: How is it being transferred?

Just minutes before the call, Dr. Hamberg had received word that a western Ohio dairy herd had tested positive, which he said “is a little too close for comfort.”

Still, his overall calm and practical demeanor comes from having dealt with Pennsylvania’s poultry industry that is well-acquainted with avian influenza at times through history since the early 1990s, and most recently in 2022-23.

“We’re operating under the bird-to-cow, largely waterfowl, migrating ducks and geese, and focusing on using biosecurity measures to keep them away from cattle,” said Dr. Hamberg. “They excrete virus in large amounts.”

He talked about the poultry farm pattern in Pennsylvania in 2022-23, which also suggests wild bird to farm transmission vs. farm-to-farm spread.

“There is some evidence that could suggest this could be cattle-to-cattle, but this would be novel and relatively new to the world,” said Hamberg, airing his doubts. “As we build a better picture of what it looks like and how it moves through a population, we can do more to protect our cattle. Either way, brush up your biosecurity plans.”

On transfer to people, Hamberg said: “What we know with this virus – as seen in birds – it can infect people, but rarely. Several dozen have been infected worldwide (over time), but what we don’t see is person-to-person transmission or concern for consumers.”

He noted that the Texas dairy employee confirmed positive this week makes two farm workers in history: “one from cattle and one from poultry.”

Wild waterfowl still the focus

The investigation so far has looked at a wide variety of data and didn’t find any common links, other than wild migratory waterfowl, said Dr. Hamberg, and it’s the same strain of the virus in these waterfowl in the Pacific and Central Flyways.

He also noted that the poultry industry’s experience has been that songbirds and starlings “are not effective transmitters. We’re focused on waterfowl.”

Dr. Hamberg advised:

1) Keep a close eye on your cattle,

2) Ramp up your biosecurity,

3) Keep wild waterfowl away from ponds and standing water,

4) Keep cattle fenced off from water where wild waterfowl congregate,

5) Keep outdoor waterers clean and free of wild waterfowl,

6) Clean up roadkill and manage mortalities.

Penn State extension veterinarian Dr. Hayley Springer also mentioned roping off areas where wild bird feces proliferate to keep tractors from running through it between feed commodities and barn entry.

“There is no definitive evidence that this can move from cow to farm birds or vice versa, but still work on biosecurity to keep those populations separate on the farm,” said Hamberg. “If we get a case in cattle in Pennsylvania, we would quarantine that farm, with a minimum set of standards to ensure movement on and off farm does not cause increased risk to other farms in the community.”

For example, a quarantine may mean milk off farm might be permitted to go to a specific plant following specific biosecurity restrictions such as last stop on a run for the milk truck or feed truck – things of that nature. A quarantine would permit milk off the farm only for pasteurization. Such permits would be case by case IF a dairy herd in Pennsylvania would have detected HPAI A(H5N1).

Bottomline, said Hamberg, this virus deemed to be affecting cows is “remarkably unremarkable, and there is no evidence that it has become mammalian-adaptive,” he said. “Usually when we see spillover events, the transmission between animals tends to be very poor. There is no specific mutation identified in this strain to be mammalian adapted, and it is still unclear what that looks like going forward.”

Hamberg said department guidelines for cattle movement and biosecurity would be forthcoming for Pennsylvania and to find them at www.centerfordairyexcellence.com along with other resources, including advice from Dr. Hayley Springer, who gave practical tips for minimizing waterfowl risk on dairy farms.

Two days earlier, in the April 1 webinar put on by NMPF and attended virtually by around 1000 people, veterinarians noted that while HPAI is believed to be introduced by migratory wild birds, veterinarians do not yet understand the mode by which it entered dairy cattle systems for the first time in history, nor do they know how it may or may not be transferred between cows. (Listen to NMPF’s Jamie Jonkers who moderated the webinar discuss it on a podcast March 28.)

Investigations look for multiple ‘pathways’

It’s important to note that veterinarians are operating off the premise that they want to understand the entirety of the situation to be sure other pathways are not involved in the underlying illness in dairy cows causing decreased lactation, low appetite, and other clinical signs.

Toward that end, federal and state agencies continue to conduct additional testing in swabs from sick animals and in unpasteurized clinical milk samples from sick animals, as well as viral genome sequencing, to assess whether HPAI or another unrelated disease may be underlying any symptoms.

Dr. Mark Lyons, National Incident Health Coordination Director at USDA’s Ruminant Health Center, noted on the NMPF webinar that while HPAI A(H5N1) has been detected through the sampling, he suggested that it might not be the only disease or factor at play.

“I don’t think we have a clear picture to say that HPAI is causing the illness we’re seeing displayed in these cattle. I think there’s still a chance that we might be seeing multiple different pathways playing out,” said Lyons, adding that additional sampling needs to be done with the expertise of producers, industry persons, and veterinarians.

Because lateral transmission has been recognized, but the mode of transmission is unknown, biosecurity measures are the most proactive approach producers and industry personnel should be focusing on to protect herds, said Lyons.

When asked if the disease is being found in non-lactating animals, Lyons said that he was unsure of how much testing, if any, had been done on non-lactating cattle because it has been lactating animals that have exhibited clinical signs.

On movement and biosecurity

While Dr. Lyons said USDA has no plans to ban or restrict cattle movement at this time, it is recommended to limit movements as much as possible and to test any animals destined for movement to be sure they are clear of HPAI at the time of movement. Animals moved should be quarantined.

USDA and its partners are now advising veterinarians and producers to:

1) Practice good biosecurity,

2) Test animals before necessary movements,

3) Minimize animal movements, and

4) Isolate sick (and new) cattle from the herd.

In the NMPF webinar, veterinarians said the focus of biosecurity should be protecting the dairy, preventing exposure to cattle and calves, and precautions for caretakers and veterinarians, including:

1) Manage birds and wildlife on the dairy,

2) Delay or stop movement of animals,

3) Quarantine animals for 21 days because the incubation period is unknown,

4) Clean and disinfect trailers and equipment,

5) Delay or stop non-essential visitors,

6) Those who do come into the operation should wash hands, change clothes, clean boots, or use disposable boots,

7) Any equipment coming onto the farm should be disinfected before entering,

8) In “abundance of caution”, on farms where HPAI A(H5N1) has been confirmed or is suspected, milk intended to be fed to calves or other livestock (including pets) should be pasteurized or otherwise heat-treated,

9) The recommendation for caretakers and veterinarians working with confirmed or suspected animals is to wear gloves, N95 masks, eye protection and monitor themselves for respiratory or flu-like symptoms.

When asked about the safety of infected cows destined to be culled, Dr. Lyons said cows exhibiting signs should not be sent to slaughter. He noted that, “in an abundance of caution,” milk samples should be used to screen animals from affected herds before moving a cow to slaughter, whether or not signs are being shown.

With the strength of the federal meat inspection process, “we have no reason to believe the meat would be unsafe, and we have not found any virus presence in meat tissue. But, out of extreme caution, we want to do testing or limits. There are already parameters and buffers in place not to send sick animals into the slaughter system,” said Lyons.

Experiences on affected dairies

APHIS reports that affected animals have recovered after isolation with little to no associated mortality reported.

Dr. Brandon Treichler, quality control veterinarian for Select Milk Producers has witnessed infected herds and has been in contact with others dealing with the disease firsthand. During the NMPF webinar, he shared the signs and symptoms of what they have experienced.

Initial signs are consistent among all the herds. Farms that have the monitoring capability to test conductivity in overall milk will see a spike because of the immune response occurring, he said.

Initially cows rapidly go off feed, stop ruminating or stop showing signs of chewing their cud, and their milk production is suddenly gone, he explained, noting that what milk they do have is thick and resembles colostrum. Not all four quarters are always affected this way, which is a curious finding in how the disease presents.

Other symptoms vary. Some cows have firm, “tacky” manure, which could be a secondary issue from dehydration or cows not being able to regulate fluid. Other cows exhibit systems of diarrhea. Various respiratory symptoms have been reported with the most common being clear nasal discharge and increased respiratory rate. Fevers have been reported in some herds while others have not.

Secondary infections are also coming in behind the original HPAI A(H5N1), perhaps accounting for variability in reported symptoms.

Most severe cases are shown in older and mid-lactation cows, with some severe cases happening in first lactation or in fresh cows. There has been very little evidence of it impacting dry cows or young stock.

“That’s not to say they aren’t being affected, but the most obvious signs are decreased rumination and loss of milk production, so the signs might not be observed in non-lactating animals,” said Treichler.

This could also be why it doesn’t seem to be affecting beef animals whether cow/calf or feedlot. “It’s not to say they aren’t being affected at all, but it’s hard to see these severe cases in these (non-lactating) groups,” he said.

“When people are talking about the 10-20% of the herd involved they’re talking about these severe cases. My personal clinical impression is that much of the lactating herd is impacted by this because when you look at things like rumination and milk production, they’re down overall on a herd level,” said Treichler. “At some point most of the cows in the herd are being impacted by this, so you’ll have mostly subclinical cows.”

The reported production loss estimates range from 4 to 20 pounds/cow/day to 10 to 30 pounds/cow/day.

The worst of the cases appear to be within the first week of the outbreak. Affected cows begin to go back on feed within a few days, and herds go back to pre-infection milk production and SCC levels within a month of the initial outbreak. Some cows will recover, but there are some that will not recover, especially if secondary infections follow.

While cows might show clinical signs of mastitis or abnormal milk, it is not a mastitis pathogen that can be treated traditionally. It does not respond to antibiotics.

Additionally, abortions are being observed in herds that have been through the process, probably not due to the virus, but most likely from high fever in the immune response or metabolic stress that the cows went through. Future fertility or cyclicity problems could be expected.

“Please don’t hesitate to report to your veterinarian. I know it’s scary, but it will help the whole industry if we can find out about it and learn from each case,” said Treichler.

Responding to a question about what treatment plans are working for sick cows, Dr. Treichler said supportive care includes keeping them hydrated and treating any obvious symptoms from secondary issues, and treating for fever if there is fever.

There is much yet to learn in this rapidly evolving situation. Biosecurity efforts are the best course to follow as more testing and epidemiological study is underway to understand all that is a part of it.

This story follows Farmshine’s coverage in the March 29 edition

-30-

Pingback: Pa. orders dairy cattle movement restrictions, testing to protect against HPAI spread; detections now in 8 states | Ag Moos