By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, July 12, 2024

HARRISBURG, Pa. – Pennsylvania State Veterinarian Alex Hamberg stressed the importance of early detection and wants to step up voluntary milk sample surveillance for the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI H5N1) in dairy cows, according to comments on the July 10 Center for Dairy Excellence monthly HPAI industry call.

There have been no detections in Pennsylvania dairy herds and no active poultry detections at the present time. Hamberg wants to keep it that way, and he wants to make sure that if the virus surfaces here, it is his office — working in collaboration with dairy farmers — that are the ones who detect it, by being proactive.

A scenario playing out right now in Colorado gives clues about why.

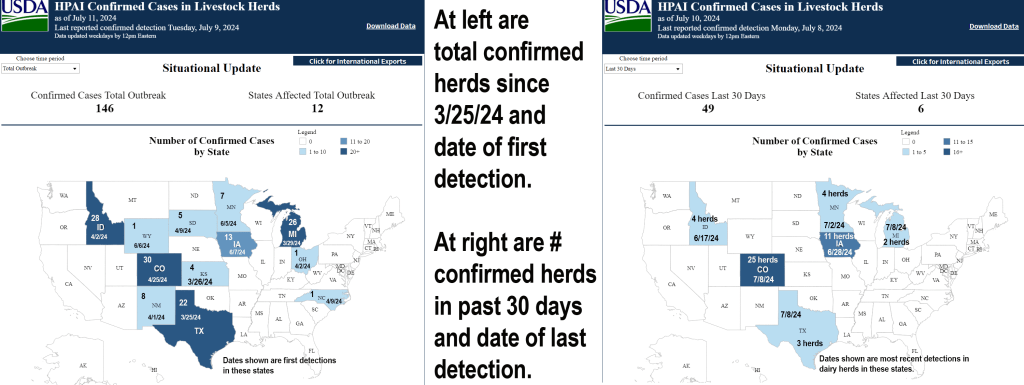

Colorado has had 30 dairy herds affected since April, the most of any state, representing more than one-fourth of the 110 dairy farms in the 13th ranked milk state, where the average herd size is 1827 cows. Of the 30 total herds affected since April, 25 were in the past 30 days, and three in the past week.

Colorado also has the most poultry flock infections in the past 30 days — one layer operation and three meat growers (two turkey). Two workers in Colorado, one in 2022 on a poultry farm and one recently on an affected dairy, were confirmed with the virus, but recovered quickly. Public risk is extremely low do to food safety protocols, testing, and pasteurization. Precautions are in place for those working closely with infected animals, including PPE states are making available through USDA, such as eye and face protection, gloves and disposable overalls.

Even though Colorado has had bird flu in poultry locations (and wildlife) across the state since the worldwide outbreak began in 2022, the recent detections in dairy cows and poultry appear to be occurring in the northeast part of the state, especially in Colorado’s number one dairy and poultry county.

In fact, on July 9, the Colorado Governor declared a disaster for Weld County, which was necessary to receive federal support to take mitigation steps and depopulate 1.8 million layer hens on an infected poultry farm neighboring an infected dairy operation.

Michigan and Texas are not out of the woods. On July 8, the APHIS 30-day ‘situation’ status showed 48 herds in six states had H5N1 in the prior 30 days. Michigan was down to one and less than a week away from being dropped off the status map. Texas was down to two and 10 days away. But on July 9, the APHIS update showed both states had a new case, and Colorado had three new ones.

This put the 30-day status at 53 herds in six states, which dropped to 49 herds in six states on July 10. The U.S. total since March 25 is 146 dairy herds in 12 states.

“The positive thing is that once a herd tests positive, it is then tested on a regular basis. In Ohio, for example, there are no more cases. This shows the possibility of getting rid of this in dairy,” said Dr. Ernest Hovingh, PADLS director.

For poultry, however, the risk is ever-present with no reprieve since this particular HPAI outbreak began in 2022. It continues to be found on poultry farms and in wild birds, worldwide, according to USDA veterinarian Dr. Michael Kornreich. He reported eight commercial flocks and four backyard flocks have been detected in the past 30 days, nationwide.

Unlike dairy cows that mostly recover, HPAI is lethal to poultry. A positive test means the whole flock is promptly depopulated, and quarantine zones are established. This is a big concern for the Ag Department in Pennsylvania, where the 2022 Ag Census showed poultry surpassed dairy as the number one ag product.

Hamberg described a scenario that has occurred in at least one state where both dairy and poultry are currently affected: “Dairies waited to report sick cows for testing. By the time they did, other dairies were infected, and poultry had become infected.”

He observed that the virus appears to be shedding in milk up to two weeks prior to clinical signs in cows. Anecdotal evidence suggests that workers had conjunctivitis (pinkeye) before cows showed clinical signs in herds at the beginning of the outbreak, Hamberg noted.

“Early detection is important not just to protect our own dairy farms but also our neighboring poultry operations. If you suspect HPAI, report it, work with us, and we will work alongside you to address it and protect you,” he said. “This is why we need the surveillance data.”

To-date, one Pennsylvania dairy farm has enrolled in the voluntary PA Lactating Dairy Cow Health Monitoring Program to achieve ‘monitored herd’ status.

In a separate program, one Pennsylvania processor has enrolled in testing at the milk hauling level.

Dairy farms can enroll online. They will receive a box with everything needed to collect and ship bulk tank samples at no cost. As a ‘monitored herd,’ they avoid pre-movement testing for interstate cattle transport.

Three consecutive weekly bulk tank samples are collected, followed by testing of a few animals from the sick pen to achieve ‘monitored herd’ status. Continuing the weekly bulk tank testing will continue the ‘monitored’ status. If a positive is detected, the farm keeps its ‘monitored’ status, and any movement or biosecurity concerns are addressed between the Dept. of Agriculture and the farm management.

What researchers know at this point is “transmission from farm to farm is heavily driven by ‘fomites.’ That means people, equipment, and animal movements,” said Hamberg.

“Robust testing helps us figure out where it is, to eliminate it by counter measures. We can do that while it is still definitely controllable, and not in a wildlife reservoir. But if it spills back into wild birds and circulates in them again, we may have a bigger problem,” he explained. “We need surveillance data to figure out where it is. If that is all negative, that’s great news. If we get a positive or two, we know we are doing something and have a chance to contain it.”

Could early detection have changed the course for the dairy/poultry interplay unfolding in Colorado? “Maybe,” said Hamberg. “There was no sharing of workers between affected farms, but there was cohabitation — poultry workers living with dairy workers — and this is a known transfer mechanism. Early reporting might have made a difference in that.”

-30-