By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, April 12, 2024

HARRISBURG, Pa. – Add North Carolina to the list of states with confirmed detections of bird flu in dairy cattle.

While the USDA APHIS website had not yet updated its daily listing at 4 p.m. on April 10, the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services issued a press release at noon stating: “The National Veterinary Services Laboratory has detected Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) in a dairy herd in North Carolina.”

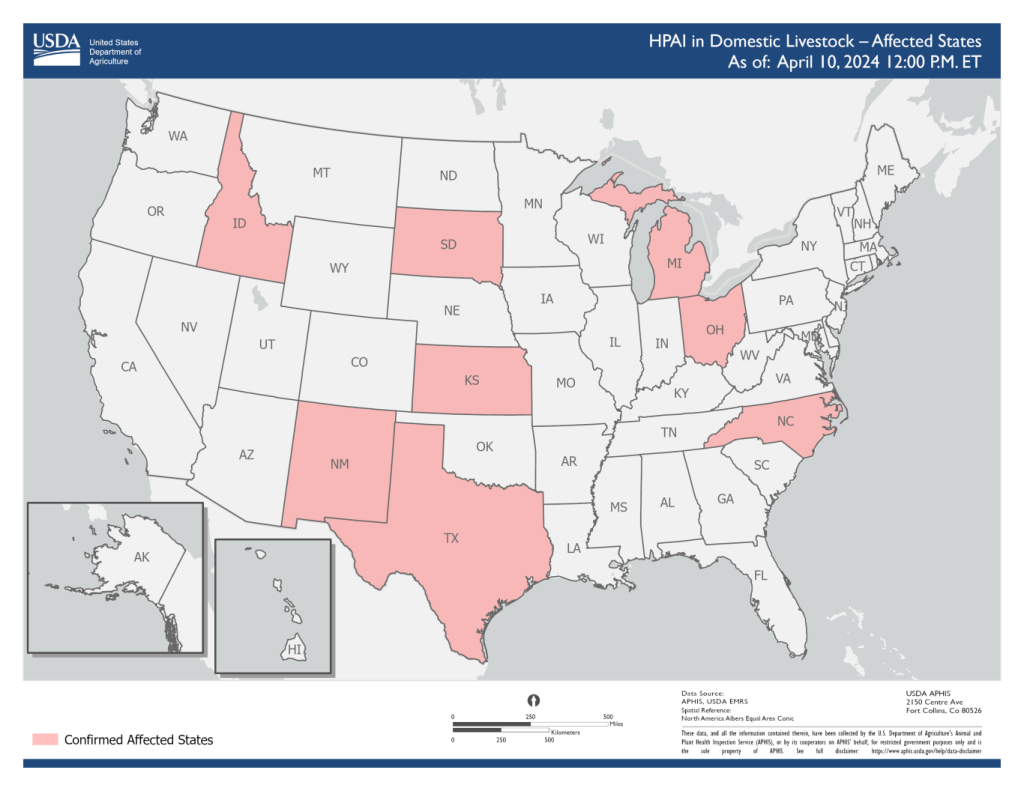

This would bring the total to 19 dairy herds in 8 states: Texas (9), Kansas (3), New Mexico (2), Michigan (1), Idaho (1), Ohio (1), North Carolina (1), and South Dakota (1). (South Dakota was added to the list after Farmshine went to press)

“This is an evolving situation, and we are waiting for more diagnostics from NVSL and will work collaboratively with our federal partners and dairy farmers in North Carolina,” said Agriculture Commissioner Steve Troxler. “It is important to note the FDA has no concern about the safety or availability of pasteurized milk products nationwide.”

Introduction of HPAI A(H5N1) to dairy cattle has been shown to be by migratory birds, and USDA epidemiological studies show it may also be spreading between cows.

“Both are sources of introduction,” said Pennsylvania’s Assistant State Veterinarian Dr. Erin Luley, answering questions during the second Center for Dairy Excellence (CDE) weekly HPAI update conference call April 10.

USDA, in fact, reported on April 5 during a UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) virtual meeting of scientists that they “have not seen any true indication that cows are actively shedding the virus and exposing it to other animals, or that it is replicating within the body of the cow — other than within the udder.”

This is why lactating dairy cattle are the focus of multiple state orders in recent days regarding restrictions, testing, and quarantine of interstate dairy cattle movement.

“The virus might be transmitted from cow to cow in milk droplets on dairy workers’ clothing or gloves, or in the suction cups attached to the udders for milking,” Dr. Mark Lyons, USDA Director of Ruminant Health, shared during the international meeting, according to a University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) report.

The UNMC report also noted that dairy cattle are frequently transported from the southern parts of the country to the Midwest and north in the Spring. They are floating the possibility — without naming specific herds or locations — that all affected cows may trace back to a single farm. In fact, the confirmed positives in Idaho, Michigan, Ohio and now North Carolina are on premises where cattle had previously been brought in from Texas.

“The virus appears to replicate in mammary tissue, so those cattle that are not lactating do not have a high viral load for transmitting the virus,” noted Dr. Luley in the CDE call.

According to the epidemiologic data released by USDA, she said, the early cases, especially in Texas, New Mexico, and Kansas, show that HPAI was predominantly introduced by wild birds.

“For a few other detections, including in Michigan and Ohio, the main source seems to be the movement of animals from other states,” said Luley.

To prevent spread to dairy cattle in the Keystone State, the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture issued an Interstate and International Quarantine Order on April 6 for the restriction of movement and pre-movement influenza testing of dairy cattle from states where HPAI has been detected in dairy cattle.

When asked how the Pennsylvania Order compares to what other states are doing, Dr. Luley said “ours is the most stringent. The goal is preventing the spread of this condition into our state — to proactively protect the animals in our state to the best of our ability.”

In short, the Pennsylvania Order applies to dairy cattle, not beef cattle. It restricts all movement of dairy cattle into the state for any reason from farms where HPAI has been detected.

Furthermore, dairy cattle coming into Pennsylvania for sale or show, must do pre-movement testing if they come from a non-affected farm in a state where HPAI has been detected. Those states to-date are Texas, Kansas, New Mexico, Idaho, Michigan, Ohio, and now North Carolina and South Dakota (updated by APHIS April 11).

The USDA APHIS website is updated daily and includes a map showing the states of HPAI detection in dairy herds at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections/livestock

This should be consulted before movement of cattle from other states into Pennsylvania, to be sure the appropriate restrictions and pre-movement testing are applied.

Dairy cull cows from any state with a positive case, even if coming from a non-affected farm, that are destined for Pennsylvania slaughter facilities, are not subject to pre-movement testing if the animals are slaughtered within 72 hours of entry. However, they must go directly to a slaughter plant and cannot be commingled with other cattle at an auction center.

Calves under one year of age are considered low risk and are exempt from pre-movement testing at this time.

Pre-movement testing must be done through a laboratory in the national network, and the results must accompany the shipment. Acceptable test samples for non-lactating dairy cattle, such as bred heifers, are nasal swabs; however, the only acceptable test sample for a lactating animal is a milk sample. Again, this is because the mammary system is where HPAI viral replication is being seen.

“At present, the disease has not been shown to affect beef animals,” said Luley about why the Order is written only for dairy cattle.

She gave examples of how the Order is being implemented:

If a producer wants to import a group of bred heifers from Texas, and they come from a farm that had a confirmed positive, those heifers would not be allowed to come to Pennsylvania. If they come from a non-infected herd in Texas, they would need pre-movement testing with the farm’s veterinarian overseeing the sampling and the analysis done by a national network lab.

If a producer in Ohio wanted to move cull dairy cows directly to a slaughter facility in Pennsylvania, if they are coming from a currently unaffected farm in that state, no testing would be required. But, if they are from an affected farm in that state, those cull cows would not be permitted to come to a Pennsylvania slaughter facility.

If a producer from Virginia, where there have been no detections of HPAI, wanted to ship fresh heifers to Pennsylvania, there would be no requirement to test because no infection has been detected to-date in that state, so there is no movement restriction and no pre-movement testing requirement.

There are no quarantine orders on milk movement at this time; however, this would change if HPAI were detected anywhere in Pennsylvania. If that occurs, the state would enact its “Temporary Order Designating Dangerous Transmissible Diseases” provision, now amended to include “Influenza A Viruses in Ruminants.”

In such a scenario, a quarantine would be set up for an affected farm to work with animal health officials and their veterinarian to show appropriate biosecurity measures to qualify for a 30-day milk movement permit. With that permit, their milk could go only to a processing plant.

“The viral sequencing matches the circulating strains in the (migratory bird) flyways,” said Luley. “We can impose a quarantine, but we can’t apply it to migratory waterfowl, so that risk remains, and it is the reason why biosecurity is our best tool.”

USDA Wildlife Service biologists Tom Roland and Kyle Van Why said their winter surveillance of migratory waterfowl and raptors in the Susquehanna watershed, for example, shows the virus is here in these populations, but at lower numbers than last year.

Even though starlings and pigeons are not good transmitters of the disease, they do carry it, and the numbers of these birds are high, so they bear watching.

Roland said that with restrictions on how to handle migratory birds, including resident Canadian geese and vultures, farmers should contact the national hotline at 1.866.487.3297 to work with the Wildlife Service for case-by-case strategies to manage and mitigate bird use of the farm. They have tools that are not generally accessible.

Dr. Hayley Springer, Penn State extension veterinarian, said opportunities are available to help dairy farms build their own biosecurity plans. In-person open houses are being held across the state at county extension offices, check with yours.

“Everyday biosecurity is the first line of defense, and effective for Influenza A,” said Springer. Biosecurity Kits to assist are available from CDE.

According to Dr. Luley, one dairy farm in Pennsylvania reported signs that met the case definition closely enough to undergo the HPAI testing protocol, which thankfully turned out to be negative.

Dairy farmers seeing signs in their herd should contact their veterinarian. Clinical signs of HPAI in cattle, which the American Association of Bovine Practitioners this week announced it will rename as Bovine Influenza A, include:

1) a sudden drop in feed intake with concurrent decreased rumination and rumen motility;

2) a subsequent marked drop in herd level milk production with more severely affected cows having thickened milk that almost appears like colostrum or may have essentially no milk at all; and

3) changes in manure, especially tacky to dry manure.

Visit https://www.centerfordairyexcellence.org/hpai-industry-call/ for recordings and other valuable information.

Read Farmshine at farmshine.net for continuing coverage and previous articles April 5 and March 29