PREVIEW – By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, June 30, 2023

WATTSBURG, Pa. — Kevin and Amanda Bush are fourth generation dairy farmers with their children Ava, 17, Clara, 6, Jarrett, 5, Georgia, 1, and 110 milk cows. On an early June day, unseasonably cold even for Erie County, Pennsylvania, a visit to the Bush Family Farm shed light on farmers’ concerns about a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposal to designate 798,000 acres of French Creek watershed as a National Wildlife Refuge. Potential land acquisitions could begin a year from now if approved by the USFWS Director later this summer. Mark Muir from Erie County Farm Bureau, who raises hay and livestock, and Brian Young, whose extended family operates a nearby seventh generation farm were part of the discussion of the proposed protection area that would stretch 117 miles from Chautauqua County, New York south through Erie, Crawford, Mercer and Venango counties, Pennsylvania. The region is home to farms and other businesses that are the lifeblood of rural towns and counties. They use conservation practices and a lot of grazing and haying, with a vested interest and pride in their stewardship and relationships with existing conservation efforts.

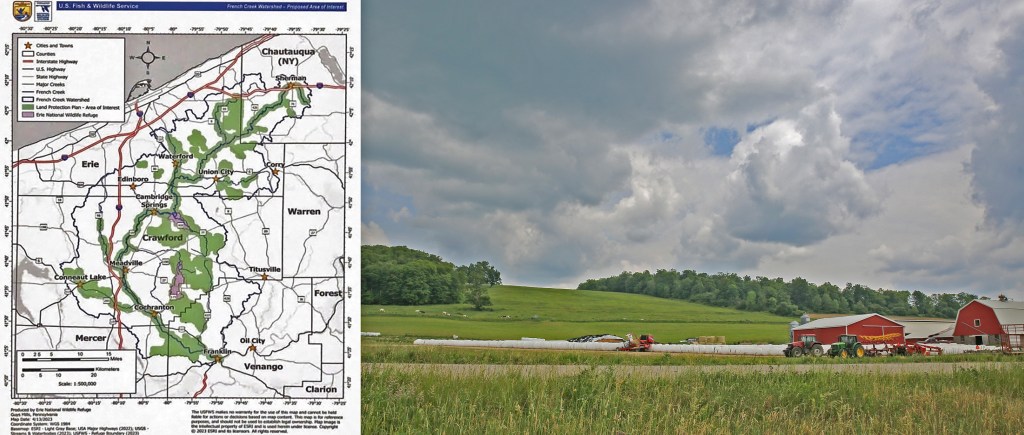

On a map showing land protection ‘areas of interest,’ whole farms are included, not just setbacks (see map in main story below). This includes many dairy farms ranging from small herds managed by young next-generation farm families, like the Bushes, to larger farms with multiple generations of families involved. USFWS wants to purchase land or use permanent easements for whole farms. ‘You can still farm it,’ they say. But when specific questions were brought to an April meeting, the locals came away with very few answers. They anticipate another meeting in July.

Why are farmers concerned? They fear future use of eminent domain and farming restrictions as dominos start to fall. A National Refuge designation with Land Protection Plan, is perpetual. They fear the loss of rented ground to feed their cows. They worry about their towns and counties. They want to know the minimum goals of the project so they can have an intelligent conversation with USFWS. They have asked for scientific studies to be shared that show how the freshwater mussel population and other aquatic life are actually doing today vs. 10, 20, 30 years ago.

It feels like the start of what could become a gradual 30 x 30 land grab. Surely, if this was happening in agricultural communities of southeastern Pennsylvania along the Susquehanna River in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, instead of northwestern Pennsylvania in the French Creek watershed, there would be much more attention paid. See main story below as published in July 7, 2023 Farmshine, and stay tuned as we follow this developing story.

They say National Refuge for mussels will move at snail’s pace, but farmers see muddied water ahead

MAIN STORY – By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, July 7, 2023

WATTSBURG, Pa. — The rural French Creek watershed is in the sights of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for a proposed National Wildlife Refuge that could span nearly 800,000 acres, stretching 117 miles from the headwaters in Chautauqua County, New York across the Pennsylvania border through Erie, Crawford, Venango and Mercer counties.

Meetings this spring in Meadville and Edinboro were part of the ‘public scoping’ phase. They were packed with citizens and fraught with questions, deep concern and objections.

An initial public comment period ended May 19.

Vicki Muller, the proposed Refuge’s project manager, told local television station FOX-66 that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) is “looking to protect and preserve more wildlife habitat within the French Creek watershed, so this plan is just the beginning stages of that.”

Mentioned were freshwater mussel species, said to be the only populations east of the Mississippi, along with several species of fish, wetlands, and migratory waterfowl.

Land acquisitions are about a year away, Muller confirmed.

Farmers and other community members, along with managers of existing conservation efforts, say federal land acquisition is not necessary to meet environmental goals because those who are living, working, farming in the region already work with local conservationists to manage the land in ways that have been recognized for success.

French Creek was named Pennsylvania’s “River of the Year” in 2022.

Opponents of the Refuge argue that its designation could place federal regulation on private landowners for perpetuity. They say an accompanying Land Protection Plan (LPP) could take properties and money off local tax rolls, move land ownership away from local residents, and take products generated on the farmland away from local communities, weakening the region’s economy and food security.

To top it off, USFWS could offer no evidence that this would improve — at all — the status of French Creek and its aquatic life, nor any evidence that either are in trouble.

USFWS is currently in the process of reviewing public comments and stakeholder feedback and is developing a final plan for approval by the USFWS Director later this summer, according to a Q&A document at the webpage devoted specifically to the French Creek proposal at https://www.fws.gov/project/evaluating-new-refuge-lands-french-creek-watershed.

A June 4 ‘Public Scoping Recap’ is also provided at this webpage, stating the proposal is not yet an official proposal because it is still in the ‘public scope and biological environmental assessment’ phase.

The webpage indicates that the framework would be built after they get the buy-in, after they get the National Refuge designation and LPP approved, and after they complete the biological environmental assessment. That’s when officials say they can answer the probing questions of locals about environmental and land acquisition goals.

Isn’t that putting the cart before the horse?

One of the strategies being used here is to protract the conversation and soothe public concern with assurances that the Refuge to save mussels will move at a snail’s pace.

Essentially USWFS is looking to designate land now for decades of acquisition and that it will answer specific questions as the process moves forward working collaboratively to refine the plan after the designation and plan are approved.

Such circular talk makes farmers and landowners skeptical, uneasy.

Within the “land protection areas of interest” on the ambitious map, there are both small and larger farms, many of them dairy farms as well as beef cattle, crop and produce growers.

“I started looking at the map, and I see I am an area of interest. Everything I own is an area of interest,” said Mark Troyer, a potato, corn and wheat grower, in an on-camera interview during the Edinboro meeting. “I think we can work and live hand-in-hand (with wildlife) and have been doing a great effort. We’ve already been doing a great job.”

Concerns about eminent domain were specifically raised. Muller stated this will not happen.

Landowners are not convinced. They want to know the endgame.

They want to know what happens once there is an approved LPP with specified land acquisition timelines. What happens to their farms if they are eventually surrounded by acquired land? What happens to the farms outside of the areas of interest that will find themselves next to a National Refuge? What is the ultimate land acquisition goal?

What are the actual environmental goals, and why does the federal government need to acquire the land to meet those undisclosed goals, instead of supporting existing local conservation efforts that show measurable success?

They share the concern that once the designation and LPP are approved, this could take on a life of its own… forever.

According to the USFWS Q&A, the land protection plan will take decades to complete as the number of willing sellers and the availability of funding will determine the timeline.

With that in mind, U.S. Congressmen Mike Kelly (R-Pa.) and Nick Langworthy (R-N.Y.), whose congressional districts cover the “areas of interest” in the draft proposal, along with U.S. House Ag Committee Chairman Glenn ‘G.T.’ Thompson (R-Pa.), led a letter calling on the USFWS to reconsider federal designations on private land.

In the letter, the members of Congress recognize that a healthy, vibrant ecosystem along French Creek must continue to be protected, but also that local farmers and residents are better suited than Washington bureaucrats hundreds of miles away to dictate how this land is best protected.

Mark Muir with the Erie County Farm Bureau grows hay and raises livestock in the area. He has been involved in the meetings, asking questions at the front end of this proposal.

Farmshine met in June with Muir at the Bush Family Farm outside of Wattsburg in Erie County. He was joined by Kevin and Amanda Bush as well as Brian Young, whose extended family operates a nearby 7th generation farm.

The Bush farm has been in the family since 1939. French Creek borders it, surrounded by grasses across the road from the dairy barn and hillside grazing paddocks. The Bushes also rent crop ground in the watershed.

They and others are concerned that once a final plan is developed and approved later this summer, land acquisitions from willing sellers could eventually morph into a land-grab that won’t stop until all of the “areas of interest” are federally owned or controlled by the USFWS.

The designation of the land as a National Wildlife Refuge and the approval of an LPP would be the first concrete steps.

“We are told there is nothing set in concrete yet,” says Muir, “But we had many questions they couldn’t answer at the meetings. We tried to talk to them about farm BMPs (best management practices), but they didn’t understand the concept.”

Because the USFWS is still in the ‘public scoping, comment review and final development’ phase,’ officials won’t engage in land use questions or what-if scenarios. They don’t answer questions that help farmers understand the ultimate impact because they say that completion of the Refuge would be “decades away.”

“Decades away” is really tomorrow for most farmers who continually look ahead at their operations and land use, making plans for future generations.

“At the end of the day,” says Young, “Fish and Wildlife can target any wildlife and the ecosystem areas that an environmental assessment deems necessary. They are not like the BLM or NRCS. The USFWS is comparatively small and does not have the cross-correlation to agriculture.”

Furthermore, land acquisitions are funded by duck stamp sales, land access fees, and other sources of revenue that make USFWS less reliant on tax dollars to use their authority. In other words, Congressional oversight — from an appropriations standpoint — is lacking.

If a final plan and Refuge designation are approved, the gradual creep of land acquisitions would begin, giving USFWS oversight of current working lands that could affect the fate of farming in the region, in particular dairy and beef cattle.

Without data and without answers, this becomes “a slippery slope with no guard rails,” says Muir. “We want to be objective about it, and to have those conversations at a July meeting. We need certain information to have a meaningful conversation so we can see if and where we might be able to work together.”

Meanwhile, Kevin and Amanda and their four children milk 110 cows and raise their youngstock. They are a small family dairy on land that the Bush family has been farming for 85 years.

There is not only a legacy here, but also progress as they have implemented many BMPs, just as other farms have throughout the region.

Muir notes that NRCS funding, and other cost-shares, don’t seem to flow as much in the Northwest direction of the state.

He says BMPs on farms could improve even more with cost-sharing and a productive dialog, which is preferable to a multi-decade federal plan to acquire the land.

“If this is supposed to be to save the freshwater mussels, and they have these dollars to spend, why not try other approaches first?” Amanda wonders, adding that they could promote BMPs that farms can do even better than what they are already doing, and cost-share some of that. “It would go a lot farther instead of designating a Refuge, buying up land, and disrupting family farms, local towns and their economies.”

“We do no-till and minimum tillage here. We do cover crops wherever we can, and we are working now already with the County Conservation District,” Kevin adds.

Bottom line, these and other young farmers want to continue farming and producing food for their communities. They are part of these rural communities where cows and crops, grazing and haymaking, youth programs and showing at the county fair are part of the fabric.

Maybe it’s more important to identify the rural community fabric that is at stake — the younger generations who want to continue. As farm families of all sizes, they are accustomed to working with USDA, NRCS, county conservation districts, local conservation efforts that all have connections to agriculture, so they speak the same language.

But when Fish and Wildlife makes its entrance with a draft proposal for a National Refuge of immense proportions across so many miles, acres and counties — having no crossties to agriculture — that’s a scary place for any farm family to be, and it can lay threadbare the fabric of the communities beyond the farms.

To be continued

Pingback: Does a watched pot boil? National Refuge proposal ‘paused’ in NW PA and SW NY; Fish and Wildlife says new draft coming | Ag Moos