By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, October 11, 2024

MADISON, Wis. – “I’m in Wisconsin, and on the graph (below) it looks like producers in Order 30 are having to decide between less money with an Order or even less money without an Order. Am I wrong and is there a silver lining?”

That was the crux of the question one dairywoman asked during the American Dairy Coalition’s (ADC) ‘Winners and Losers’ seminar and press conference Oct. 3 at World Dairy Expo. Over 35 farmers, industry representatives, and media professionals gathered to hear insights about USDA’s recommended decision on changes to Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) price formulas.

American Farm Bureau economist Danny Munch was the invited presenter, followed by time for questions, moderated by Kim Bremmer of Ag Inspirations, and opportunities for networking and farmer-to-media connections during the remainder of the two hours.

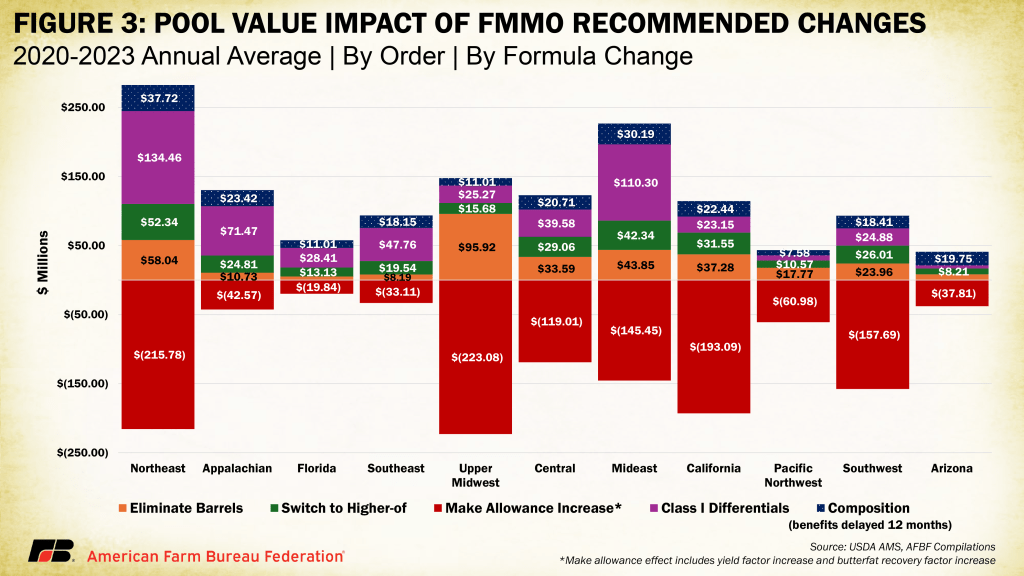

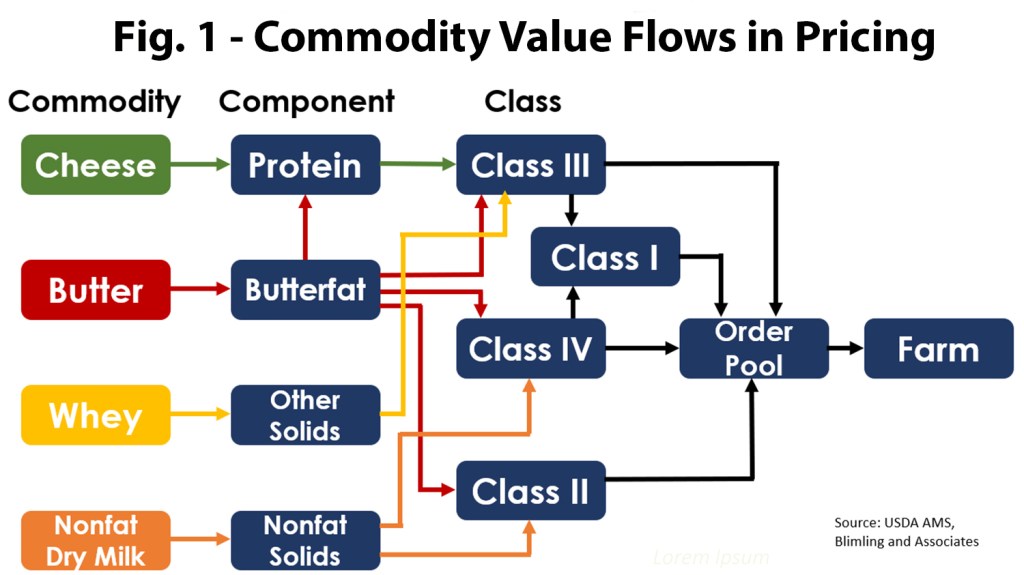

At issue was the impact on FMMOs with more cheese and less fluid milk, that would experience the negative impacts of a proposed hike in processor make allowances without the positive buffer of higher Class I location differentials.

Bremmer said over 126 individuals and organizations provided comments to USDA. The comment period ended Sept. 13.

During his visit to Expo on Oct. 4, Ag Secretary Tom Vilsack said USDA would issue a final decision in mid-November. Also on Oct. 4, USDA held a webinar explaining the producer referendum expected in January. (Look for more specifics in a future Farmshine, and check out the Farm Bureau recap here)

The short answers to the above question appear to be yes, yes, and yes. With an Order, producers in some regions will see lower FMMO blend prices. Without an Order, they would lose minimum prices altogether and other important FMMO functions.

The silver lining? Munch pointed to better competition currently for milk, and he sees opportunity for milk in the future as consumers focus on protein.

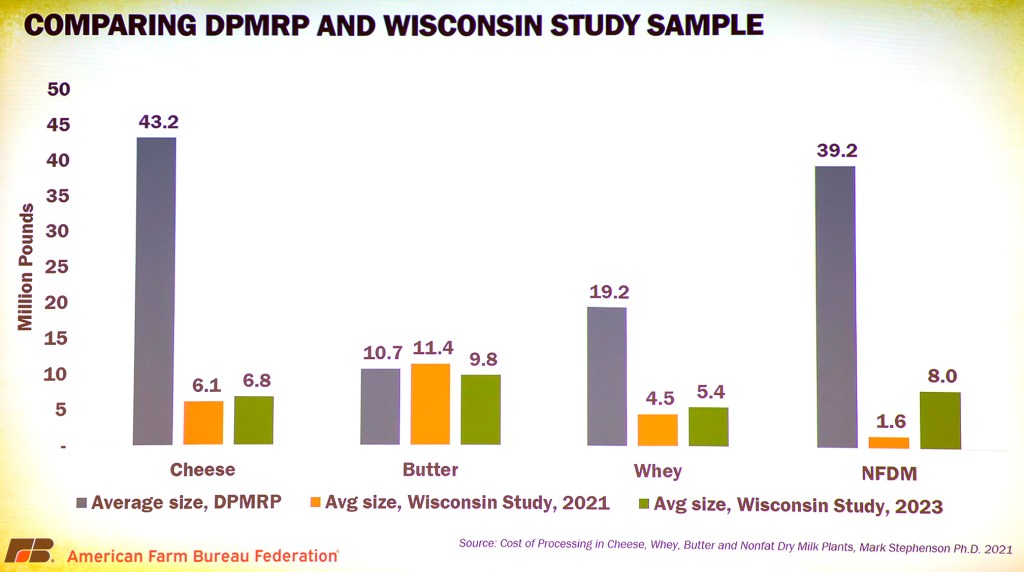

New to the discussion was make allowance data compiled by AFBF for its official comment at the Federal Register showing the average plant size of processors participating voluntarily in the Stephenson Survey relative to the average plant size of processors reporting to the NASS Dairy Product Manufacturing Survey (below)

The average size and volume of the plants in the voluntary cost of processing survey is 5 to 20 times smaller than the size and volume of plants reporting to USDA on price and production. This is further evidence that mandatory surveys are the only fair way to examine and set make allowance levels.

ADC reports that farmers have called with questions and concerns about the FMMO changes they will vote on. Part of ADC’s mission is to inform dairy farmers and help them understand factors like this that affect their businesses, said Bremmer.

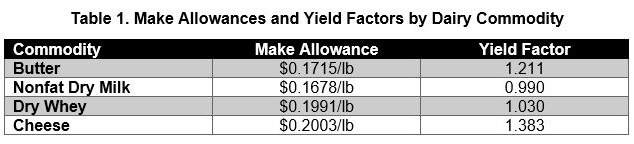

For example, it’s helpful for farmers to realize that current make allowances equate to $2.17 to $3.17 per hundredweight in deductions already in the pricing formulas to cover the cost of converting milk to butter, cheddar cheese, nonfat dry milk, and dry whey.

The proposed new make allowances add 70 cents to $1.00, depending on class utilization, bringing the total deduction to about $2.89 to $4.07 per hundredweight, maybe more.

The splitting of Class I into a two-mover pricing system is also causing discontent and concern. On the one hand, USDA would restore the ‘higher-of’ method for conventionally pasteurized fluid milk but use an ‘average-of’ method with a rolling and delayed adjuster for the extended shelf life (ESL) fluid milk products. This new milk class was not vetted nor defined during the hearing.

Also of concern is the delay in implementing positive updates to milk composition standards that have not been updated since Order Reform in 2000.

USDA’s recommended decision applies to all 11 FMMOs nationally but will be voted on by eligible (pooled) producers in each Order, individually.

A two-thirds ‘yes’ vote within each individual Order continues that Order with the changes. If the two-thirds threshold is not met by either producer numbers or volume in an Order, then the result is termination of that Order.

Producers do not have the option of voting separately on the five pieces of the USDA decision, nor do they have the option of voting to keep the FMMO pricing formulas as they are currently.

Economists with National Milk Producers Federation have stated previously that 65 to 70% of the U.S. milk supply is marketed through cooperatives that tend to bloc vote for their producers, but this percentage can vary on an individual Order basis.

USDA determines voting eligibility, based on whether milk was pooled in the reference period selected by each Market Administrator.

“When we get down the road to the vote, and if we vote ‘no,’ that will dissolve the Order, right?” asked one dairy farmer. “What opportunity does any geography have to reorganize a new Order to fit what works for them?”

Munch said producers could start a process to create a new Order, but it would still be required to use the same price formula rules because these will apply to ALL Orders uniformly. In contrast, he noted that USDA leaves pooling and depooling rules to be decided individually by each Order.

One member of the media pressed Munch to speculate on what happens if a western Order votes no, but an eastern Order votes yes?

“People always want me to speculate on what happens if California or the Upper Midwest vote out their Order(s). What we’ve seen in the past in unregulated areas, or areas with state orders — they still base a lot of their pricing on the nearby Federal Order system,” he responded.

“If we remove more milk out of the Federal Order system, does that system then play less of a role in pricing milk, and does that unregulated market start to dictate and suck milk out of the regulated areas, if you’ve taken out some of the large milk production states? That’s just some speculation, something to think about in the long term,” he said.

On a more immediate basis, Munch said that if an Order is terminated by this vote, “farmers lose protections like timely payments and component verifications, and the minimum prices. You could end up with a patchwork.”

He pointed out that USDA did not raise make allowances by the full amount requested by processors, but also did not go with the more modest increases requested by the cooperatives.

In their post-hearing comments, processors voiced great unhappiness with the decision, he said, because they didn’t get the multi-year increases to even higher levels.

“We don’t blame USDA for trying to come up with a middle ground… we just don’t have the data. The way hearing processes work is they collect this data brought by stakeholders and try to come up with a compromise that works for everybody,” Munch explained. “Our argument is that the data may not reflect market conditions, and we want to make sure that it does. We can’t get that assurance until there’s an audited, mandatory survey.”

As a standalone piece, AFBF estimates that USDA’s proposed increase in make allowances would remove an additional $1.25 billion annually from producer pool revenue, nationwide, based on past pooling data. However, USDA proposes a one-year delay in implementing the milk composition updates that would contribute $200 million annually in producer pool revenue nationwide.

Munch sees the 12-month delay in implementing the milk composition standards and the splitting of the Class I mover with an ESL adjuster as two things that appear to be “thrown in there,” with a lot of groups voicing discontent and confusion.

When asked by a reporter if the add-ons to Class I will create consumer resistance to what could be a 25-cents-per-gallon increase in retail fluid milk prices, Munch cited the hearing record where economists testified to the relative inelasticity of fluid milk demand.

He also sees great opportunity for milk: “When I go to the gym, I used to see no one drinking milk. Now I see tons of people drinking milk, protein shakes, and other things, and it’s not plant-based products. I think milk can take advantage of marketing the protein benefits that people in my generation are looking for and are willing to pay for.”

Munch was asked if AFBF will recommend how its dairy members should vote.

“We will not make that recommendation. We take positions based on our policy, which includes opposing any make allowance updates until we have mandatory cost of processing surveys, and other aspects related to our policy book,” he replied. “It’s up to our members to make those voting decisions, and there is a regionality to this, so we don’t get involved at that level.”

Florida producers, for example, “will be okay with the new rules” because the over 80% Class I utilization brings with it higher location differentials. The Upper Midwest, on the other hand, has been at roughly 5% Class I and 93% Class III, so there is very little benefit from the Class I changes, but those producers are subjected to the highest make allowance deductions for Class III products, which is 95% of their blend price.

-30-