By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, August 2, 2024

No ‘snubber’ on USDA’s higher whey make allowance proposal

The whey market is the one to watch right now as the daily CME spot market sped higher again this week, and the dry whey spot price is now above the 60-cents-per-poind mark!

No ‘snubber’ on new whey make allowance means farmers would have PAID processors to take the ‘other solids’ in their milk last summer.

One thing for the industry and USDA to keep in mind regarding the proposed rule announced July 1 is that the higher make allowances, if implemented, include a nearly 7-cents-per-pound raise in the dry whey processor credit. That can be a real bully when markets go south — considering there is no ‘snubber’ to keep farmers from having to give away these ‘other solids’ or to PAY processors to take them as though worthless.

USDA is proposing to increase the dry whey make allowance from $0.1991/lb to $0.2653/lb — a nearly 7 cents per pound jump.

Farmers would have PAID processors to take other solids last summer

Guess what? If we were having this conversation a year ago, looking at July 2023 Class and Component price announcements, we would be writing in this column that your ‘other solids’ price would be essentially zero, meaning processors would get the lactose and whey free, and last August, if the proposed new whey make allowance was in effect, farmers would have paid processors $0.003 to take these components as if they are worthless.

If the proposed 7-cents-per-pound increase in the dry whey make allowance were in effect in July and August 2023, the new $0.2653/lb make allowance would have been at or slightly higher than the dry whey price for those two months.

When the make allowances were raised in 2008, we saw months in 2009 when farmers literally paid their milk buyers to take the other solids in their milk because the dry whey price had fallen below the then-new make allowance, and there was no snubber to stop the bleeding at zero.

July Butterfat up at $3.57, Protein slips to $1.95

USDA announced mixed trends on July 31 for the Class and Component prices used in Federal Milk Marketing Orders for July milk. Class II and IV at $21.82 and $21.31, respectively, were around 20 cents per cwt higher than a month ago and 20 to 70 cents higher than the July Class I base price ‘mover.’

Class III milk, at $19.79, slipped 8 cents from June and continues to be the lowest of the four classes as it has been for most of the past two and a half years.

All components were higher, except for protein, which slipped 10 cents per pound back under the $2 mark at $1.95/lb. Butterfat gained 3 cents at $3.57 for July. Solids nonfat also gained, valued at just over $1.00 per pound for July.

Other solids also gained, at 26 cents/lb. This is derived from the dry whey price vs. make allowance.

June All-Milk price up 80 cents at $22.80, fully $5/cwt above year ago

USDA announced the All-Milk price for June at $22.80, up 80 cents from May and fully $5 higher than a year ago. The national average butterfat test moved down 0.07 at 4.10, but was still 0.09 above year ago. The Pennsylvania All-Milk price for June, at $23.30, was also 80 cents higher than the previous month, and fat test fell by 0.06, reported at 4.01, just 0.01 above year ago. The June DMC margin was not published or available by press-time, but with a higher All-Milk price for June announced at 3 p.m. July 31st, and moderating feed costs, the June DMC margin is likely to be well above the $9.50 trigger margin at around $11.50/cwt. (Update, June DMC margin was announced Aug. 2 at $11.66).

Milk futures mostly higher, especially Class IV

Class III milk futures were mostly higher this week, except near-term September and October were down a few cents per hundredweight. Class IV futures were steady to higher across the board. On Wed., July 31, Class III milk futures for the next 12 months (Aug24-Jul25) averaged $19.44, down 2 cents from the Jul24-Jun25 average on the previous Wednesday. The 12-month Class IV average at $20.92 for the 12 months Aug24-Jul25, also 2 cents below the Jul24-Jun25 average a week ago.

Whey and powder skyrocket, but formula price survey lags

Trade was active with high volume movement on Class IV products, butter and nonfat dry milk powder. Trade was light for Class III products cheese and whey.

The whey market is again the big story as the daily CME spot market continues trading at price levels well above the weekly National Dairy Product Sales Report (NDPSR). The NDPSR prices are the ones that USDA collects in mandatory processor pricing surveys to use in the Federal Milk Marketing Order end-product pricing formulas. The NDPSR whey price is the one USDA AMS plugs into the FMMO pricing formula for Class III and ‘other solids.’

While spot bids for dry whey rallied to a whopping 62 cents per pound Wednesday, July 31, with 3 loads trading the first three days this week, and the weekly average price at 60 cents… the NDPSR for week ending July 27 is still back at 46 cents/lb — a 14-cent per pound deficit vs. the spot market, and 9 cents lower than the previous week’s spot market.

The CME spot market for cheese was mixed with the barrel premium over blocks widening to 7 cents per pound this week as barrels traded firm while blocks moved lower. In the weekly NDPSR, barrels are a scant half-penny higher than blocks.

The CME daily spot market for 40-lb block Cheddar was pegged at $1.9150/lb Wed., July 31 ($1.93/lb average for the week). This is 2 1/2 cents lower than the prior Wednesday with 3 loads trading the first three days this week. The 500-lb barrel cheese price, pegged at $1.9750/lb was unchanged compared with a week ago; 3 loads traded Monday through Wednesday.

The NDPSR for week ending July 27 pegs block cheese at $1.9482/lb and barrels at $1.9533/lb.

In the Class IV product complex, butter firmed up to move higher this week, shrugging off the Cold Storage Report indicating inventories were running 7% above year ago at the end of June. A whopping 26 loads of butter were traded on the CME cash market Monday through Wednesday this week. On Wed., July 31, the spot price was $3.1275/lb — up nearly 4 cents from the previous Wednesday with the weighted average for the week just over $3.10/lb — right where the NDPSR butter price landed for the week ending July 27.

Grade A nonfat dry milk trade was active again this week on the CME spot market, advancing to $1.2450/lb by Wed., July 31, up another penny from a week ago with a whopping 20 loads changing hands the first three days.

Contrary to historical patterns, the NDPSR moved the opposite direction. Again, this is the price used in FMMO pricing formulas. Nonfat dry milk for the week ending July 27 hung back at the $1.18 mark, declining a penny from the prior week despite the 7-cent spot market advance last week. CME spot prices are now at a 6-cents-per-pound premium over the NDPSR.

Total packaged fluid milk sales in May continue outpacing year ago

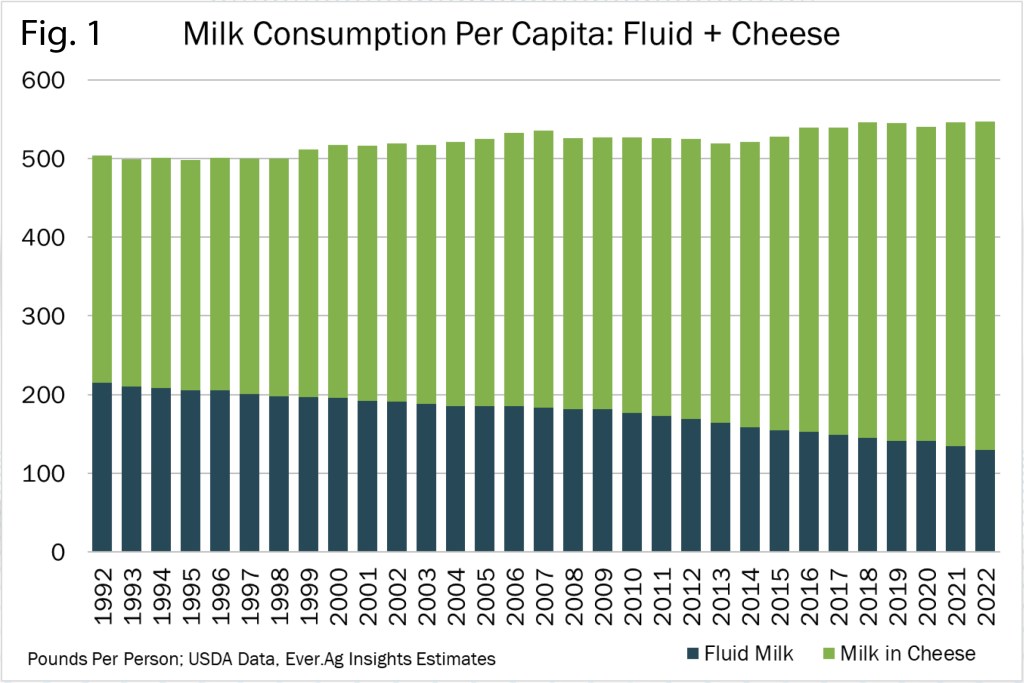

U.S. fluid milk sales continued outpacing year ago in May, according to the USDA’s Estimated Total Packaged Fluid Milk Sales Report released last Friday, July 19.

The report showed May sales were up 0.3% compared with a year ago, following the big 5.9% jump in April. In fact, fluid milk sales have been higher year-over-year (YOY) for six of the past eight months.

Year-to-date (YTD) sales continue to beat year ago, up 1.3% for the Jan-May period, and when adjusted for Leap Year, YTD 2024 sales are up 0.6% vs. 2023.

Leading the charge again is the largest volume category: conventional whole milk sales, up 1.8% YOY in May, plus organic whole milk sales, up 28% YOY in May.

Conventional whole flavored milk sales were down 13% from a year ago in May — a function of what fat percentage is offered, not necessarily what consumers may have selected — as the reduced fat (2%) flavored milk sales rose 3.5% in May. By contrast, organic whole flavored milk sales were up 31% YOY in May.

Total Organic fluid milk sales of all fat levels were up 6.3% in May YOY and up 7.8% (Leap Year Adjusted) for the first five months of 2024 vs. year ago. They represent 7% of the YTD total of all fluid milk sales.

The ‘other fluid milk products’ category continues to make double-digit percentage gains, up 45% YOY in May and up 37% (Leap Year Adjusted) YTD vs. year ago. This category represents 2.2% of total fluid milk sales. The report does not separate out the ESL products in each fat percentage; however, lactose-free milk brands are included in the ‘other products’ category.

Year-to-date milk production down 1%

U.S. milk production fell 0.8% in June compared with a year ago, despite the national herd reportedly having 2000 more milk cows than a year ago, according to USDA’s monthly milk report this week. The report also revised the May total lower by another 0.2% or 30 million pounds.

Year-to-date milk production for the first half of 2024 is down 0.3% compared with the first half of 2023 even with an extra day of production in 2024! When adjusted for Leap Year, first half 2024 milk production trailed year ago by 1%. It would not be surprising to see USDA come back and trim the June tally lower, later.

In the Northeast and Midatlantic Milkshed, Pennsylvania’s production fell 2.2%, Vermont down 2.8%, and New York down 1.2%.

In the Southeast, Florida gained 4.9% with 4000 more cows while Georgia dropped 8.1%, losing 8,000 cows, and Virginia saw a 4.3% drop in production vs. year ago.

The Mideast Milkshed declined with Michigan down 0.9%, Ohio 0.6%, and Indiana 1.6%, with just a 1000-head loss in cow numbers across the three states.

In the Upper Midwest and Central Plains, Iowa grew production by 1.2%, despite being hit with bird flu in June, Minnesota was down 1%, South Dakota up 8.3%, and Wisconsin up 0.9%.

Western States saw production declines, except for Texas up 3.1% with 13,000 more milk cows than a year ago.

DMI / NMPF talk supply and demand

Fluid milk, yogurt, butter and other than American-type cheese all posted positive annual growth in domestic commercial use during the March-May 2024 period, according to the July edition of the joint DMI and NMPF market report released July 23rd. The report cites significant export growth for all types of cheese and whey protein concentrate and isolate. However, when looking at domestic and export sales of all products combined, the usage is described as “relatively flat to lower” in the March through May period.

The DMI / NMPF report observes that U.S. milk production has nearly had a year’s worth of volumes charting below prior year levels, but “continued increases in average component composition of producer milk has enabled U.S. dairy farmers to supply available demand for dairy products while keeping inventories of key products relatively stable,” the report stated.

Overall supply-and-demand balance in the industry has been good enough to move dairy product and dairy farm prices and margins higher in recent months, without significantly reversing the gradual reduction trend in retail dairy product prices that has occurred over the past year, according to the report.

While dry skim milk usage is down 48% in the March-May period, this is a function of the lower production of skim milk powder (down 24.5%) and nonfat dry milk (down 12.5%). Inventories at the end of May trailed year ago by 4%. Domestic and export markets can only ‘use’ what is ‘produced’ and available in a commodity category in the first place.

But the DMI / NMPF market report did not even mention imports… So here’s the deal:

The U.S. imported 41% more Whole Milk Powder in first-half 2024 vs. 2023,

up 150% vs. 2022!

While U.S. milk production has trailed year-ago levels for the past 10 consecutive months, U.S. food manufacturers have been quietly ramping up imports of whole milk powder (WMP), which is essentially whole milk, dried.

WMP imports were running 170% above year ago, cumulatively, for the first four months of 2024. May and June totals have slowed down from the huge front-loaded volumes January through April. Still, the cumulative year-to-date WMP import volume at 5.5 million pounds for the first six months of 2024 is 41% greater on a volume basis compared with a year ago.

This is a stunning increase because the Jan-June 2023 WMP import volume was already 77% greater than the first six months of 2022. This means Jan-June Whole Milk Powder (WMP) imports have grown 150% in two years. That’s a volume increase of 1.49 million kgs or 3.29 million pounds. WMP is basically farm milk from another country, in bulk dried form, not a specialized product. It can be used in processing virtually any dairy product, containing all of the milk components — both fat and skim solids.

Total non cheese imports at 10.4 million kgs (21 million pounds) for the first half of 2024 are up 5.9% vs. 2023 and up 41.4% vs. 2022.

Cheese imports, on the other hand are up slightly from a year ago (1.4%) and down 6.27% from 2022.

On the export side of the ledger, the U.S. sold 2% less total milk solids volume overseas in May, which is mainly because skim milk powder, whole milk powder, and other milk protein powder exports were down 8 to 12% from a year ago. Butterfat exports were down 16%.

Cheese exports, on the other hand, were up 27% in May and dry whey product exporter were up 6%. Fluid milk and cream exports were up 2%.

This makes sense because the U.S. dairy processing paradigm has shifted. The U.S. is making less butter and powder (Class IV) and more cheese and dry whey (Class III).

The U.S. is consequently exporting less milk powder and butterfat (Class IV) and exporting more cheese and dry whey products (Class III); while at the same time importing more whole milk powder and non cheese products, while cheese import volumes remain stable.

30-day H5N1 detections drop to 33 in 6 states, hot spot Colo. requires milk testing

As of July 31, 2024, the current confirmed cases of H5N1 in dairy cows within the past 30 days decreased to 33 herds in 6 states. Of these, 24 are in Colorado, the hot spot by a long shot. The state issued an order July 22nd to require mandatory bulk tank milk testing, except raw milk dairies, which are encouraged to do so voluntarily.

Other states with confirmed cases within the past 30 days are: Minnesota (3), Idaho (2), Texas (1), Iowa (1), and Michigan (1). Cumulatively, since the beginning of the outbreak on March 25, 2024, there have been 173 detections in 13 states.

Enrollments in the national voluntary dairy herd status bulk tank testing include 21 herds: Michigan (7), New Mexico (4), Pennsylvania (3), and 1 herd each in Kansas, Nebraska, North Carolina, Ohio, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas.

Will we see PA milk bills moove?

The Pennsylvania State Assembly has a few dairy bills waiting to moove on through both chambers again towards the end of a two-year legislative session. We’ve seen this movie before, where the House votes to allow Pennsylvania whole milk produced on Pennsylvania dairy farms to be served in Pennsylvania schools, and where the House votes to allow the state-mandated Pa. Over Order Premium (OOP) to be collected and distributed to farms by the state instead of leaving it open to loopholes that strand the dollars through creative cross-border deals.

In prior years, such milk bills would move through Committee and even get passed by the House, only to be stuck in a chairman’s desk drawer in the Senate. If we look back far enough in the history of milk bills in the Pennsylvania legislature, we see on other occasions a long awaited milk bill passed the Senate only to be stalled out in the House. Will this year be any different? Who knows? Election years are funny-seasons.

Earlier this month, Senators Elder Vogel and Judy Schwank, the chair and ranking member, respectively, of the Senate Ag Committee introduced legislation to allow the state to collect the state-mandated OOP and distribute it to farmers. A similar bill had been introduced in the past two legislative sessions on the House side by Rep. John Lawrence, but Vogel and Schwank were unconvinced to move it in the Senate.

This time, Vogel and Schwank are introducing the measure after many years of multiple hearings, task forces, and other such discussions of what on earth to do about the state-mandated OOP to make sure all of it — 100% — gets into the pockets of Pennsylvania dairy farmers, as intended.

The Vogel-Schwank rendition would “empower” the Pennsylvania Milk Board (formerly known as the Pennsylvania Milk Marketing Board) to administrate the process of collecting and distributing the premium with involvement of the Pa. Dept. of Revenue. The state would distribute the funds to farmers, milk handlers and dealers using a formula that includes cost of production, price received, and other measures.

The current method of distribution only follows the $1 premium for milk that is produced, processed, and sold in Pennsylvania, but consumers pay this $1.00/cwt premium within the minimum retail price set by the Pa. Milk Board for ALL milk sold at retail in Pennsylvania — no matter where it comes from.

For decades the debate over the Pa. OOP has had its moments where farmers thought a change would come to prevent significant gamesmanship stranding millions of dollars in premiums intended for the dairy farmers.

Yes, I am cynical. We are five months away from the end of a 2-year legislative session and four months away from an election / re-election. Forgive my gut reaction: Ho-hum…. here we go again… time and money spent on spinning this wheel of fortune. Not buying it. Stay tuned.

In June, the Senate Ag Committee passed SB 1229, which would allow the Pa. Dept. of Agriculture to provide financial assistance to dairy farmers who enroll in the federal dairy margin coverage (DMC) program.