USDA’s cross examination reveals possible flaw in simulator model result

By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, Jan. 19, 2024

CARMEL, Ind. — Shadow pricing, demand elasticity, commoditized loss of prior incentives, balancing cost, give-up cost, base differential, uniform differential, market-clearing price…

These terms ruled the day when the USDA National Hearing on Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) proposals resumed in Carmel, Indiana this week after a more than four-week recess.

The hearing began in late August. It did not conclude by Fri., Jan. 19, so it will again recess until Jan. 29.

American Farm Bureau estimates that another 270 days of post-hearing processes must follow before a USDA decision could be implemented, and even this is subject to proposals that seek a 15-month delay between decision and implementation due to potential impacts on CME futures-based risk management tools, such as Dairy Revenue Protection (DRP).

This is far from over, and hanging in the balance is the Class I price calculation, now based on an averaging method, under which farmers have lost more than $1.02 billion since May 2019 vs. the previous ‘higher of’.

Testimony Tues., Jan. 16 included Dr. Mark Stephenson, retired UW-Madison dairy economist on behalf of Milk Innovation Group (MIG), made up of ‘innovative’ and branded fluid milk processors, including fairlife, HP Hood, Anderson-Erickson, Danone North America, Shamrock, Organic Valley, Aurora Organic, and Pennsylvania’s own Turner Dairy Farms.

Dr. Stephenson delivered his bombshell for MIG that was based on analysis he did using 2016 data in a simulator model, from which he made “certain discoveries.”

First, Stephenson suggested that fluid milk is shifting to become price-elastic vs. the long-held belief that fluid milk sales are price-inelastic. This was followed up by fluid milk processor representatives showing post-Covid fluid milk sales volumes declined as prices rose.

Stephenson cautioned USDA to refrain from setting regulated prices too high, saying this would reduce returns to producers by reducing total fluid milk sales.

This suggestion was challenged in cross examination. In fact, AFBF chief economist Dr. Roger Cryan noted the FMMO focus on fluid milk was originally partly predicated on its “public good” as a food staple, almost akin to a “public utility.”

In cross examination on Jan. 17, Stephenson also revealed he was paid by MIG to analyze the $1.60 base differential, and his work began before MIG finalized its proposal to remove the $1.60 per cwt. base differential all the way down to zero for all Class I milk, nationwide.

Currently, the $1.60 base differential is built uniformly into the Class I price for every regulated county across all FMMOs. The varied location differentials are added to the base differential and spread across the revenue-sharing pools.

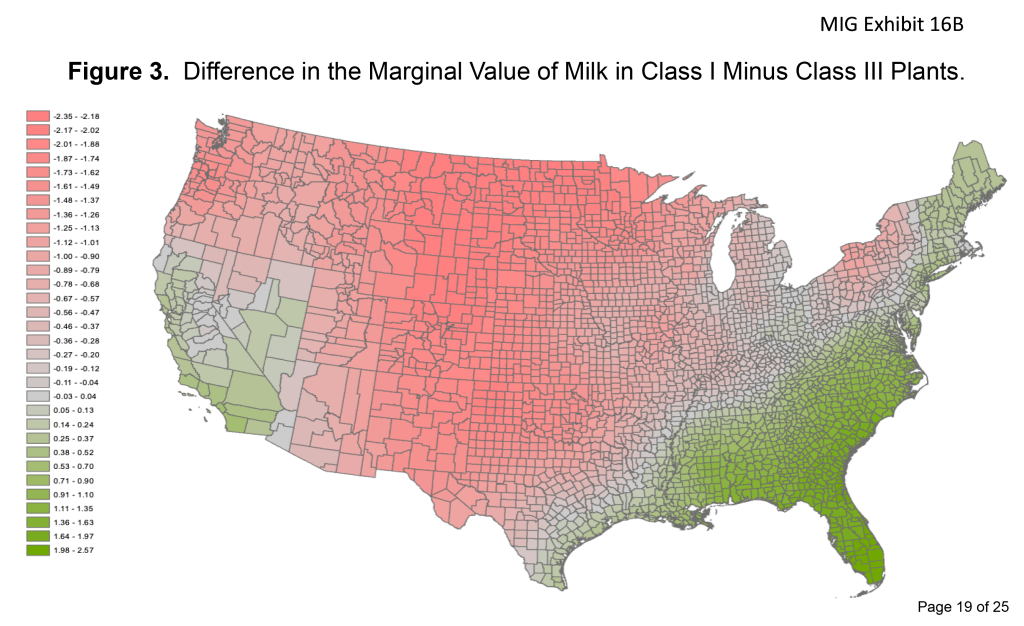

Stephenson used the U.S. Dairy Sector Simulator Model (USDSS) to develop a map as though a “milk-dictator” could efficiently “move milk to its highest global use” through various constraints.

The map showed the incremental differences in ‘Class I minus Class III “shadow pricing,” across the country.

These marginal value differences, said Stephenson, reflect the opportunity costs of getting manufacturing plants to give up milk to fluid plants in the Central U.S., where milk production exceeds population vs. the cost to balance fluid milk markets in the East, particularly the Southeast, as well as in California and southern Nevada, where population exceeds milk production.

It was the questioning from USDA AMS administrator Erin Taylor on the ‘shadow pricing’ figures in various anchor cities that prompted Stephenson to concede: “You may have caught a major flaw in what I have done here, so I would want to look at this more carefully.”

Yes, he will be back to address such questions when the ever-lengthening hearing resumes on January 29.

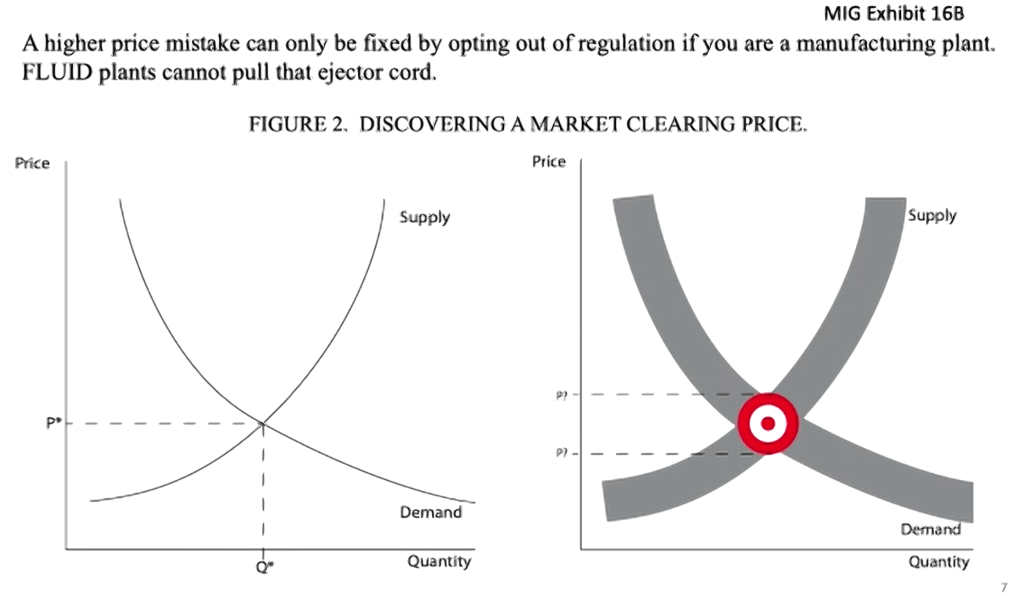

Notwithstanding exposure of a possible flaw in the simulator analysis, Stephenson said the ‘market-clearing’ price is the target to aim at, and the system of setting regulated minimum prices “should err on the side of being too-low instead of too-high.”

He said processors will pay premiums in the breach of a ‘too-low’ minimum price, but there are few options for processors to deal with a ‘too-high’ minimum price — other than to opt out of regulation for manufacturing plants (de-pool), but that fluid milk plants have no ability to opt out. They are required to remain regulated by FMMOs.

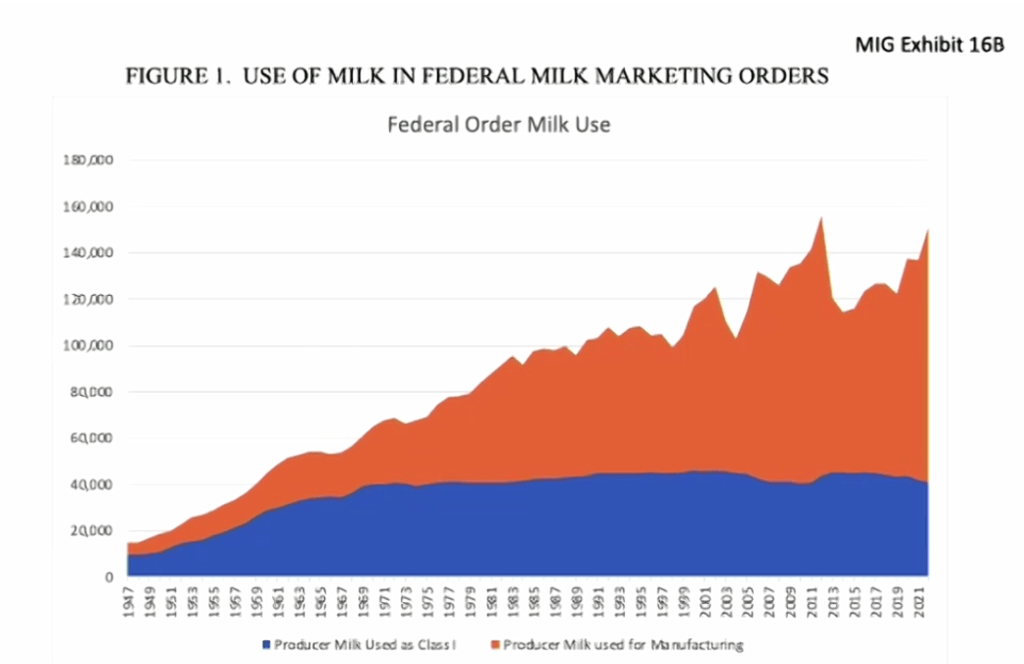

“Manufacturing is by far the largest use of milk in our dairy industry,” he said, noting that Class I fluid use at 18% of total U.S. milk production (regulated and unregulated). Therefore, he said, manufacturing use should no longer be treated in the FMMO system as “the trailing spouse in the marriage.”

On MIG’s behalf, he introduced a new way of looking at the marginal value between Class III and Class I, and a mechanical change that could be made in how the $1.60 base differential is paid as needed directly to producers, cooperatives and plants that actually supply milk to Class I plants, instead of being paid to the FMMO pools.

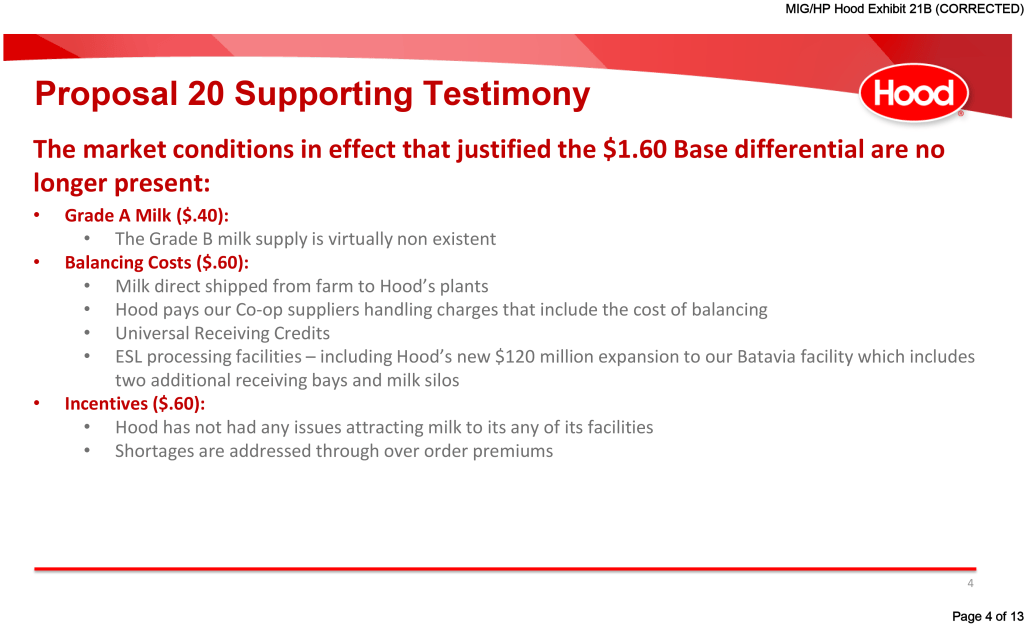

The $1.60 became a uniform part of the Class I price in the 1999 Order Reform. About 40 cents of this $1.60 was included to represent the cost of farmers transitioning from Grade B to Grade A. The rest represents ‘give up’ costs from manufacturing to Class I and balancing costs to serve the fluid market.

Stephenson backed up MIG’s assertion that farmers don’t need any of this $1.60 base differential because virtually all milk produced today is now Grade A. During cross examination, NMPF attorneys brought up the cost farmers have to maintain Grade A status. Don’t their costs count here?

Undeterred, Stephenson suggested that these costs are accounted for in the classified pricing since all milk for all uses is Grade A, today. He said that USDA uses ‘minimum pricing’ as a tool so that the regulated price leaves space for voluntary premiums that processors can pay to “incentivize something else.”

“Being chronically above the market-clearing price creates a surplus product, which the market can’t clear,” said Stephenson. “Our dairy markets have always walked on a knife’s edge. Being plus or minus 1% on milk supplies can cause some pretty big swings in prices as the markets do attempt to clear that.”

As for removing the $1.60 uniform price differential either from the price or the pool, Stephenson said it is like “other premiums” that have become “commoditized.”

He likened it to the rbST premium and milk quality premiums, saying those premiums have also become “commoditized.”

For example, when farmers were first asked to give up rbST and sign pledges, a premium was offered. Now, that premium is not paid, he said, because the practice of abandoning rbST is now “commoditized.”

Likewise, said Stephenson: “Milk quality (low SCC) has improved so much that those premiums are not there anymore. They have also become commoditized.”

So, the better dairy farmers get, the more their incentive premiums — and even big chunks of their regulated minimum price — are at risk to be cannibalized by milk buyers because the farmers have now done what they’ve been incentivized to do, so they don’t need to be paid to do it.

MIG also seeks to stop NMPF’s proposal to tweak and raise location differentials across the Class I surface map, putting on the stand some of their members to show how unfair competition arises between independent bottlers and cooperatively owned fluid milk plants in the same region.

For his part, Stephenson noted the concept of pulling the $1.60 base differential out of the pool may discourage non-productive distant pooling.

This week was certainly eye-opening as MIG is all about the processor costs with zero regard for producer costs. They even put an HP Hood representative on the stand who included the $120 million recently announced for expanding the Extended Shelf Life (ESL) plant in Batavia, NY as a “balancing cost,” that somehow justifies giving back the base differential to processors even though processors can pass their costs on to consumers, whereas farmers cannot.

Under cross examination, Hood’s representative admitted that plant-based beverages are also bottled in those so-called ESL ‘milk balancing’ facilities, along with premium products like Lactaid.

Meanwhile farmers continue to incur costs associated with a whole host of improvements that were at one time incentivized. It appears the processors expect farmers to forgo being paid for those costs simply “because everyone’s doing it” and incentives are no longer needed.

The idea here is to deflate regulated minimum prices as much as possible in search of the elusive and not-well-defined Holy Grail: the market-clearing price.

Processors want cheaper milk, and they’ve got multiple proposals to accomplish that. They want to deflate the regulated minimum milk price to free up their ability to pay premiums for “something else.”

In fact, in his testimony, Stephenson admitted that as these costs and premiums are “commoditized,” space is freed up to “pay premiums for something else.”

What is the “something else” that processors will pay to incentivize after they potentially succeed in reducing the regulated minimum price in multiple ways through multiple proposals?

Are climate premiums the next thing coming once the milk price is deflated far enough? Will USDA buy what MIG and IDFA are selling?

Stay tuned.

-30-