NMPF, NAJ say higher solids worth more nutritionally, Seek FMMO updates to avoid misalignments and disorderly marketing

By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, Sept. 8, 2023

CARMEL, Ind. – The national Federal Milk Marketing Order hearing completed two weeks of proceedings, so far, in Carmel, Indiana. The entire hearing is expected to last six to eight weeks, covering 21 proposals in five categories.

Picking up the livestream online, when possible, gives valuable insight into a changing dairy industry and how federal pricing proposals could update key pricing factors.

The first week dug into several proposals to update standard skim milk components to reflect today’s national averages in the skim portion of the Class I price.

Here is a bite-sized piece of that multi-day tackle.

National Milk Producers Federation (NMPF) put forward several witnesses to show what the outdated component levels mean in terms of underpaying farmers, and how paying for the skim portion based on outdated component levels has eroded producer price differentials (PPD), leading to disorderly marketing.

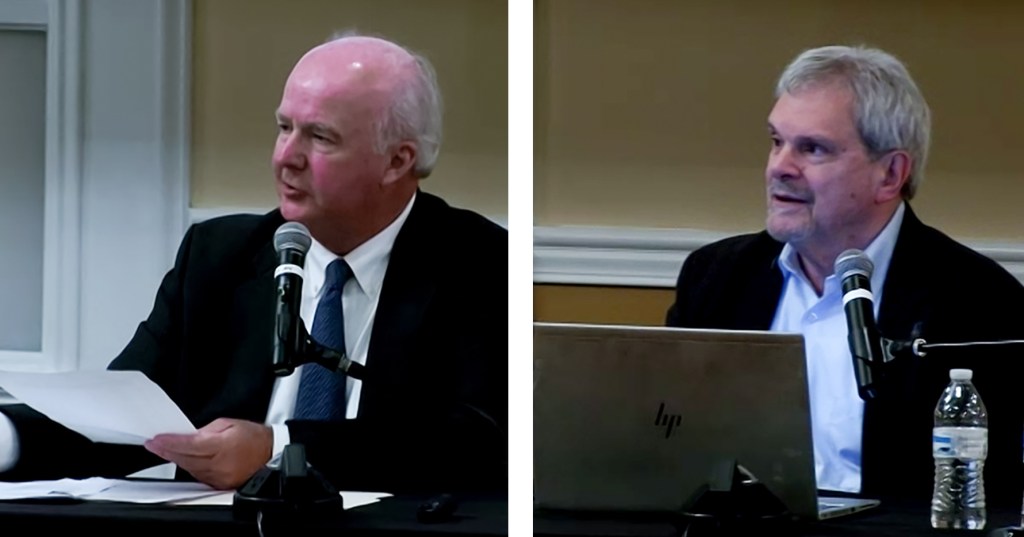

IDFA’s attorney Steven Rosenbaum grilled NMPF economist Peter Vitaliano on this. He tried on seven attempts to establish that the fat/skim orders in the Southeast don’t have component levels as high as the national average, suggesting this change would “overpay” producers in some markets.

In his questioning, Rosenbaum stressed that fluid milk processors can’t recoup the updated skim component values if those components do not “fill more jugs.”

Vitaliano responded to say that protein beverages are a big deal to consumers, and some milk marketing is being done on a protein basis. Rosenbaum asked for a study showing how many fluid processors are actually doing this.

Attorneys for opposing parties kept going back to this theme that the skim solids should not be updated because the FMMOs are based on “minimum” pricing. They contend that processors can pay “premiums” for the extra value if they have a way of recouping the extra value by making more product or marketing what they make as more valuable.

Vitaliano disagreed, saying that even though many processors do not choose to market protein on the fluid milk label, “more protein makes fluid milk more valuable to consumers.”

Attorney Chip English went so far as to ask Calvin Covington on the stand: Why should my clients (Milk Innovation Group) have to pay more for the additional solids in the milk when they are removing some of those solids by removing the lactose?

“Consumers don’t want lactose,” English declared.

Covington, representing Southeast Milk and NMPF, responded to say: “I don’t know that to be true. It is unfair to suggest all.”

Bottomline, said Covington, raising standard skim solids to reflect the composition of milk today vs. 25 years ago adds money to the pool to assist with the PPD erosion so that Federal Orders can function as they were intended and so producers are paid for the value.

As English further questioned whether consumers even care about the higher skim solids and protein levels of milk today, Covington replied: “Skim milk solids have a value in Class I, or fluid milk. People don’t buy milk for colored water. The solids give it the nutritional value. That’s the reason they buy milk. That’s why FDA set minimum standards in some states. Why would you drink milk if not for the nutritional value?”

He also pointed out that the increase in solids nonfat over the past 20-plus years has improved the consistency of lower fat milk options. As noted previously, the milkfat is a separate discussion and is not included in this proposal because farmers are already paid per pound for their actual production of butterfat in all classes, including Class I.

Under cross examination, Covington explained that the Class I price in all Federal Orders pays for skim on a standardized per hundredweight basis and pays for fat on actual per pound basis. Meanwhile, the manufacturing classes pay for both skim and fat on a per pound of actual components basis.

As skim component levels have risen in the milk, the alignment of Class I to the manufacturing classes narrows because of the differences in how the skim is paid for. When this happens, it becomes more difficult to attract milk to Class I markets. That’s one example of disorderly marketing. PPD erosion and depooling of more valuable manufacturing class milk is another example.

Covington explained the impact of this misalignment on moving milk from surplus markets to deficit Class I markets, that the lower skim value becomes a disincentive.

Vitaliano explained the depooling issue as “creating disorderly marketing conditions also, and great unhappiness when one farm is paid a certain price and another handler pays a different price (in the same marketing area). That’s disorderly unhappiness for the Federal Order program,” he said.

He noted that the fundamental reason for pooling is to take the uses in a given area with different values to achieve marketwide pooling where producers in that Federal Milk Marketing Area are paid similarly, regardless of what class of product their milk goes into.

“This removes the incentive for any one group to undercut the marketwide price to get that higher price (for themselves),” he said. “The Orders create orderly marketing with a uniform price. Depooling undermines that fundamental purpose that is designed to create orderly marketing.”

Either way, whether indirectly paying to bring supplemental milk into Class I markets from markets with higher manufacturing use, or in the case of depooling, the dairy farmers end up paying for the fallout from this erosion of the PPD.

Since the beginning, even before 2000 Order Reform, figuring the Class I base milk price had to begin somewhere, according to Covington. Federal pricing has always used the manufacturing class values in determining that base fluid milk price.

The trouble today is that Class III and IV handlers pay farmers per pound of actual skim components in the milk they receive, while the Class I handlers pay per hundredweight based on an arbitrary outdated national average skim component standard. Thus, the “opportunity cost” of moving this now higher component milk to manufacturing classes that pay by the actual pound of protein, for example, instead of by the old standard average protein levels is not accounted for in the Class I price that still uses the old standard average levels.

Pressed again on how it makes sense to raise Class I prices by raising the component level of the skim to more adequately reflect the national average today, Covington said: “It adds to the nutrition, and I stand by that. In proposal one, the price will go up (estimated 63 cents per cwt or a nickel per gallon). I am comfortable charging that extra price to Class I processors.”

Attorney English, representing MIG, retorted that, “The handlers who buy milk and then by adding a neutralizing agent remove the lactose, they’re going to pay more for the milk that they then have to process to subtract the lactose.”

Covington responded that, “There are consumers who think about lactose. There are consumers who buy lactose-free products, yes, because it is on the shelf, but it’s not all consumers.”

On the higher protein, English asked Covington how Class I processors are supposed to monetize that protein in a label-less commodity, a commodity that is declining in its share of total milk utilization?

“We are still selling 45 billion pounds of packaged fluid milk (annually) in this country,” said Covington. “Consumers wouldn’t buy that 45 billion pounds if it wouldn’t have some nutrition.”

English argued that milk is sold as whole, 2%, 1% and non-fat. It is not sold by its protein, so isn’t it “so highly regulated in ways that alternatives are not that any increase in price hinders sales of fluid milk?”

Covington acknowledged that, “yes, it is regulated, but I’m not convinced that this proposal will hinder fluid milk sales. Again, (higher components) add to the nutrition and I stand by that.”

Opponents kept coming back to these value questions, while proponents focused on the price alignment issue and orderly marketing.

To link up with the hearing livestream 8 to 5 weekdays, to read testimony and exhibits, and to respond to the virtual farmer testimony invitations made every Monday for the following Friday, visit the Hearing Website at https://www.ams.usda.gov/rules-regulations/moa/dairy/hearings/national-fmmo-pricing-hearing

-30-