By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, November 15, 2024

HARRISBURG, Pa. – Innovation on the dairy farm isn’t just the big investments that come to mind, but a mix of changes and a mindset to improve. Three distinctly different Pennsylvania dairy farms were showcased in a producer panel during the 2024 Dairy Financial and Risk Management Conference hosted by the Center for Dairy Excellence recently.

The audience of mainly ag lenders and industry representatives along with some fellow dairy farmers, had the opportunity to see how producers think through the challenges, progress, and investments, and how they manage their risk in areas such as herd health, feed and nutrition, as well as adversities they can’t control like weather, markets, and labor.

Automation at Oakleigh

For Matt Brake of Oakleigh Farm, Mercersburg, the five-year plan was accelerated in a different direction after a barn fire in December of 2019 forced the family to ask the question whether they would even continue in dairy. No animals were lost, and the 1950s parlor was saved, but they had big decisions to make about the future without a facility.

“We did a lot of praying and had a lot of difficult conversations,” he recalls.

By July 2020, they were milking 120 registered Holsteins with two Lely robots, automated feeding, automated bedding, and retained their preference for a bedded pack barn rebuilt within the existing footprint.

“We really appreciate the cow comfort we get from a bedded pack, and the longevity, which is something we are really seeing now, more than ever,” Brake explains.

They didn’t know — at first – that they would go robotic, but they did know the Lely Vector feeding system would be used for feeding in place of buying a new tractor and mixer and firing it up twice a day.

“It’s amazing to see how all these different pieces of technology play together,” says Brake.

The curtains and fans are all automated and integrated. All data points for the herd are displayed on every single milking. The system ranks cows from zero to 100 on percentage chance of illness, and the automatic sorting for individual attention is based on things like activity, rumination, production, and intakes.

“Everything just plays together in real time, without guessing. We’re still involved as managers, but the data and automation are the tools we didn’t have before. We saw an increase in production, but farming is still farming,” Brake relates, giving examples of ration changes that had to be made with a forage quality issue, and how data systems helped with early detection.

Overall, the animals are doing better in this system, and they are treating fewer cows because they are getting to them earlier.

“It’s really true that an ounce of protection is better than a pound of cure. The quicker we can give those cows the attention, the less likely they are to really nosedive on us,” he says.

Brake sees how automation saves labor in some respects, but it’s more accurate to say that, “With automation, we are better utilizing our skills. We’re able to spend our time better with the cows or focusing on priorities – like chopping corn or getting the alfalfa harvested at the right time.

“We don’t have to stop those activities two times a day or worry about if we have enough help in the parlor, and do we trust that person to stand in the parlor. The robot might ‘call in sick’ temporarily here and there, but in general, compared with some of the employees we’ve had, it’s reliable.”

Moving from just the paper DHIA to incorporating this into the electronic records, changes how they manage culling to be more voluntary than involuntary.

“We can look at space and overcrowding and begin to evaluate cows not just on milk but how efficient they are in the robots looking at deviation from the average with rankings on everything from performance in the robot to reproductive performance and past treatments and other metrics,” he explains.

Better management of the culling decisions also gives them the ability to plan how many heifers to raise. “One of the things we are doing is using more beef semen and using the system to decide who to use it on,” he says.

Renovation at Mount Rock

For Alan Waybright, innovation was the focus when he purchased Mount Rock Dairy from the Mains five years ago near Newville.

A building project was in order to update the over 30-year-old milking systems. About a year ago, they began milking in a 50-stall rotary, which changed the milking time on 2.5 times a day with each milking in a double-12 taking 9 hours, to now milking 4 times a day with each milking taking 3 hours and 45 minutes.

Waybright has been expanding from the 650 cows and 150 bred heifers he brought to Mount Rock from his prior home farm involvement at Mason Dixon, to milking 940 cows today with a 92-pound average, 4.2F and 3.3P.

Automation features were part of the rotary to reduce labor, and the calf barns include the wet barn to get them started before grouping for automatic feeders where they receive four to five feedings a day, resulting in healthier, better growing calves.

With the automated pre- and post-dipper, Waybright says the milking procedure in the DeLaval 50-stall rotary is very consistent, requiring just two employees, the first to wipe and forestrip and the second to dry and attach.

“This is a labor savings, yes, but there have been other benefits for udder health too,” Waybright reports. “When we went from the double-12 where we were hand dipping to the sprayer, a 50-gallon drum used to last seven days, now it’s three days.”

One of the innovative things he has worked on is the use of manure solids for bedding while keeping somatic cell counts low. His system uses two screw-presses dropping manure into the drum, leaving about two days’ worth of bedding at the other end with moisture levels around 50%.

They bed stalls every day during the week to use the solids as they come right out of the separator drum, adding acidifying ag lime to control mastitis.

Diversity key at Slate Ridge

“For us the secret weapon is diversity,” says Ben Peckman of Slate Ridge Dairy, Thomasville. He and his wife and high-school aged children milk 150 cows and raise 100 heifers, also feeding out all bull calves as steers.

He says there’s not one multi-million-dollar investment here, just the things that altogether add up to make a large impact.

At the dairy, he looks for ways to streamline, like ovsynch for repro. “It’s the little pieces here and there, he says, mentioning the machine with a smart phone app he purchased to do daily dry matter analysis on feedstuffs before mixing.

“Instead of always looking at the past for those adjustments, I can go out and see what the DM is right now,” says Peckman.

He fills the small sampler with three samples to get an average. “I have feed charts on my phone, pop in that number, and it changes out what I put in the mixer to get the same DM pounds,” he explains.

With feed stored in drive over piles, this is even more important to get the accurate measures each day, according to Peckman, who sees how it changes daily, firsthand.

“On a rainy day, it goes up, and on a dry, hot day, it goes down,” he says. “When changes happen day to day, testing every two weeks is not enough. My spreadsheet smooths out the changes by using the average of the past three days. When we started doing this we saw better production and components.”

A robotic feed pusher is another feed technology that’s made a difference. “We see higher intakes, fresher feed, labor savings and the ability to do this when I’m not there,” Peckman relates.

Bankers asked what ‘calculus’ goes into making such investments. For Peckman, the answer was blunt. “It’s something that improves how my herd performs but the robotic pusher does something I’m not willing to do. I’m not getting out of bed at 2:30 a.m. to push up feed.”

Other barn updates include ventilation controls and ceiling fans above bed pack areas. It’s better for cow comfort but there’s also a cost savings. “We use half as much straw and bedding with the new fans drying the air.”

His wife’s mobile milk pasteurizer is another innovation. They always fed whole milk and had a few problems when they fed it unpasteurized.

With the mobile pasteurizer, it’s two-fold: “the milk is better, but also the temperature is much better. It keeps the milk warmer, and we have healthier, better growing calves.”

Peckman really enjoys the cropping side, farming 1100 acres of diversified crops to feed the cowherd and take advantage of other markets.

“Diversity is how I mitigate risk. It’s my key technology. Diversity can’t be bought, but it pays. It helps me combat weather, combat markets, and combat other adversities in general,” he says, adding that it’s “not rocket science,” just looking at things other farmers are doing and adapting.

He does use GPS guidance for his tractors for planting and spraying, which saves seed and inputs and work off field monitoring with yield maps.

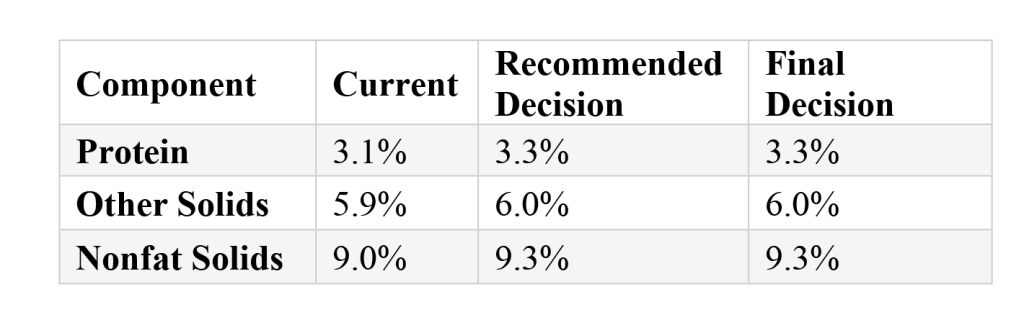

In addition to traditional corn for grain and silage and alfalfa haylage, they grows high oleic soybeans at Slate Ridge Dairy. “We saw a drastic increase in butterfat percentage,” Peckman reports.

On his silage ground, small grains are grown — triticale, wheat, and barley. The barley he harvests after it gets the head, two weeks before it would be a grain harvest, as silage for feeding heifers.

One “big new innovation” he’s excited about is male sterile forage sorghum.

“It puts a head on without developing grain in the head,” Peckman explains. “This allows the plant to concentrate on putting energy into a plant that is a high sugar crop not a high starch crop. It’s very comparable to corn silage. I take a pound of corn silage out of the ration and put a pound of this stuff right in.”

He has replaced up to 40% of his corn silage with this particular sorghum silage and would like to get to 50% because “it’s a very economical feed to grow, the seed is cheap and inputs are less. It’s working well for me, but you have to have a way to harvest it as the BMR forage sorghums don’t ‘stand’ all the way to harvest.

“We started feeding this two years ago, and our components are up.”

Another newer crop in Peckman’s diversified portfolio is milo, or grain sorghum. He says it’s economical to grow and drought resistant, and they have a market for bird seed.

The wheat is grown as a cash crop but it has been fed too. The barley he harvests is a supplement for dry corn, depending on the year. He likes to grow these crops because they make good straw to bed the cows.

Peckman is a big believer in keeping his soil covered at all times, so some of the decisions and rotations are tweaked with weather and calendar. Over the past couple years, he has added a few acres of sunflowers to the crop rotations.

“We can double crop sunflowers after wheat, and there is a viable bird seed market for those,” he says.

“Mainly, they are beautiful, and I see people enjoying them. Nobody is paying me for that part of it, but it warms my heart to see neighbors stopping with the families, taking pictures and looking at my flowers. With everything going on in the world today, if I can see someone go out and smile a little, it’s worth it.”