Whole milk, new farm bill top their bipartisan to-do list

By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, Jan. 17, 2025

HARRISBURG, Pa. – Bipartisan priorities were evident — especially on getting whole milk back in schools and completing a new farm bill — during Rep. Glenn ‘GT’ Thompson’s annual listening session on opening day of the Pennsylvania Farm Show Jan. 4th in Harrisburg.

With a thin Republican House majority, Thompson, who represents the largely rural 15th district of north central Pennsylvania, will continue as Chairman of the Ag Committee.

He introduced the more than 100 attendees to the Ag Committee’s new top Democrat, Ranking Member Angie Craig, who represents the mostly rural 2nd district of southeast Minnesota.

They were joined by Ag Committee and Ag Appropriations Committee member, Rep. Chellie Pingree, representing the 1st district of Maine, and by Pennsylvania Secretary of Agriculture Russell Redding.

Whole milk

“We got really close to getting this done,” said Thompson about his Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act after Berks County dairy farmer Nelson Troutman with the Grassroots Pennsylvania Dairy Advisory Committee asked: What’s next for the bill in the new 2025-26 Congress?

“We have to start over, but there is a lot more support this time,” Thompson replied. He doesn’t see any obstacles on the House side after overwhelming bipartisan support in the 2023 floor vote.

He expects the bill to move quickly through the Education and Workforce Committee under its new Chairman Tim Walberg (R-Mich.), a whole milk bill cosponsor. Then Thompson will work with House leadership to get it on the calendar for a 2025 vote.

He said the Senate side also looks “very promising” as Sen. John Boozman (R-Ark), a supporter of the bill, replaces former Ag Committee Chair Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.) who had blocked it.

Craig gave further assurance. She and the new Ag Committee Ranking Member on the Senate side, Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), are working together on this. “We do not see what we saw last time on the Democratic side to get this done for GT,” said Craig.

Both are Democrats from Minnesota who previously cosponsored the bill – Craig on the House side, Klobuchar on the Senate side.

Thompson credited the education and leadership of the Grassroots Pennsylvania Dairy Advisory Committee and 97 Milk in raising awareness and support. “The grassroots effort also helped improve the bill by suggesting language that makes sure the calories don’t count toward the fat in the school meal,” he said.

Pingree is also a big supporter of whole milk in schools. She was “amazed” to see all the Drink Whole Milk signs, banners, and painted bales while visiting her brother-in-law in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

“I don’t know too many states where you see something this interesting while you’re driving down the road. It’s pretty impressive. It has spread far and wide,” she noted.

ESL milk

Troutman asked if the bill could address extended shelf life (ESL) milk in schools. He is concerned about taste and acceptance by students, saying “schools should only be allowed to serve ESL milk if that’s the only option available to them.”

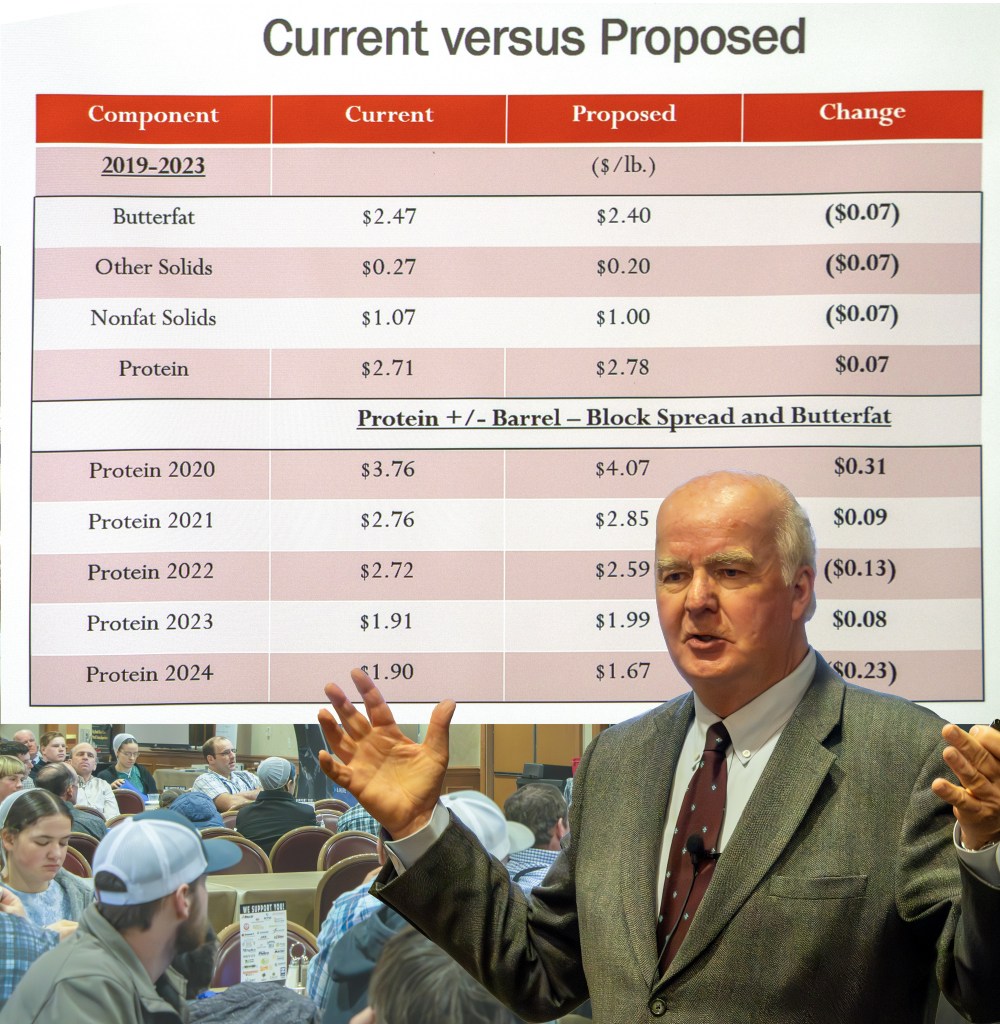

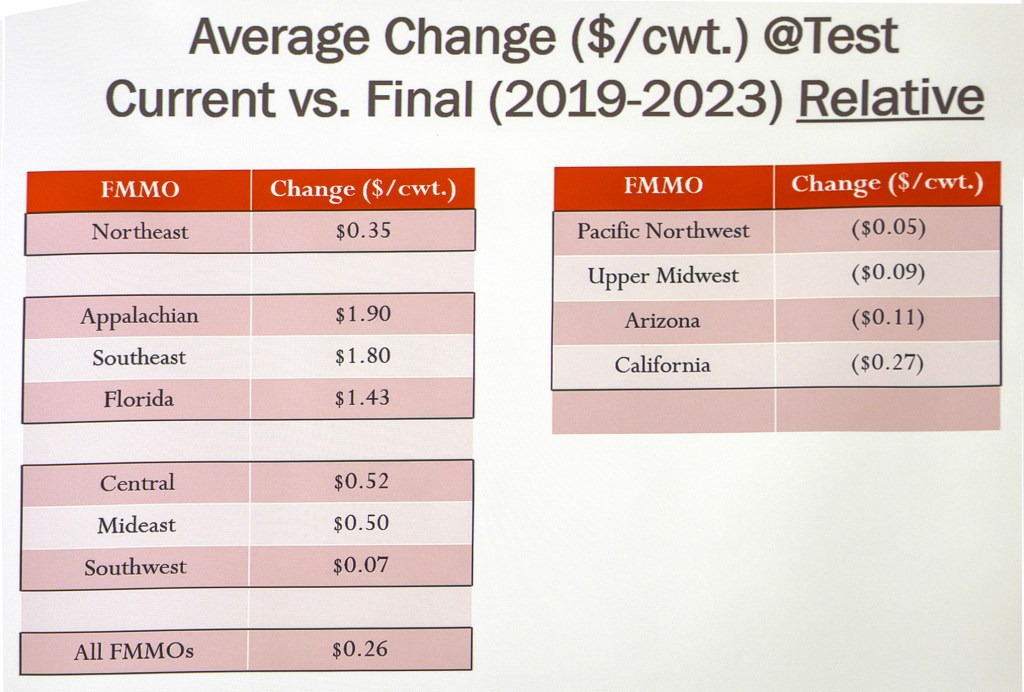

His concern arises from the volume of new plant capacity coming online across the country for ESL and aseptic shelf-stable milk packaging, along with new Federal Milk Marketing Order formulas that will price Class I milk differently based on shelf life. This creates potential competitive issues, especially in Pennsylvania, for bottlers of conventionally pasteurized milk that tends to be more local vying for school contracts with ESL milk coming from potentially more distant locations.

Farm-to-School

State lawmakers and young people in attendance voiced further concerns about the quality of school meals and the practice of schools shipping-in prepackaged meals prepared out-of-state, leaving Pennsylvania agriculture out of the loop.

They requested incentives for local farm-to-school food programs. Frank Stoltzfus, a 9th generation farmer from Lancaster County pointed to the PA Beef to PA Schools program as a successful example.

These discussions come under the jurisdiction of the House Education and Workforce Committee and its “long overdue overhaul,” said Thompson: “The Childhood Nutrition Reauthorization is where we reform and refine to update school meals. I’ll be encouraging Chairman Walberg that we do that reauthorization, and this (ESL question) is something we can certainly take a look at.”

Pingree noted “some farm bill funding also goes to school meals, and we can put more into resupplying kitchens for on-site meal prep and local procurement.”

Nutrition overhaul

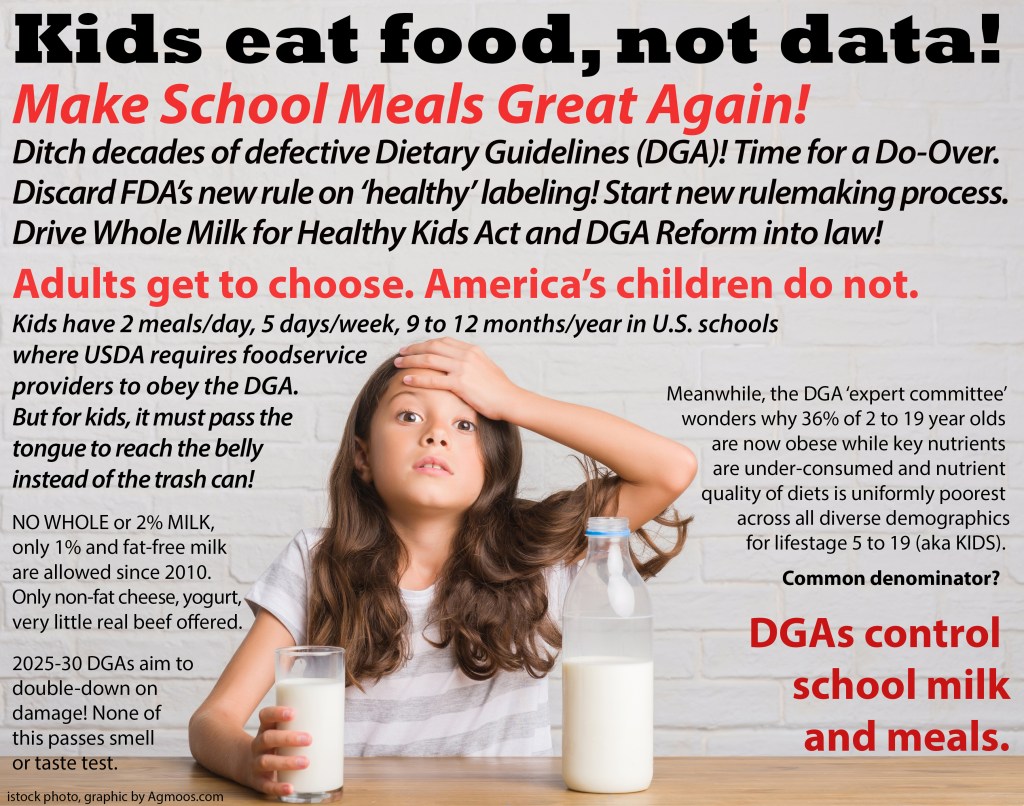

The last time Congress did a Childhood Nutrition Reauthorization was in 2010, when it tied school meals more strictly to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs).

“When it comes to nutrition, if kids won’t eat it, then it’s not nutritional, and we are seeing a lot of waste today,” Thompson observed.

On that score, he pointed to “good reforms” to the Dietary Guidelines process that will again be part of the markup of the farm bill to “take some of the food politics out of the process coming from the so-called ‘experts.’ We want science-based not agenda-based guidelines.”

Farm bill

Asked about a timeline for the new farm bill, Thompson was optimistic. New committees are still being populated, and new members will need some farm bill education.

“But I would love to see this farm bill go to committee markup in the first quarter of this year — that is my goal – and then see it move quickly to the floor,” he said in a Farmshine interview after the event. “We will continue to do listening sessions, but I want to move ahead. We’ve had great input from all across the country, but I do think it’s important that we keep listening and touching base.”

Both he and Craig shared concerns about nosediving grain prices and net farm income. They differed on what constitutes cuts vs. cost-control on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) that makes up the bulk of the now over $1 trillion farm bill. They both want the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) funds pulled into the conservation title and baseline, but they differ on removing the IRA’s climate mandates for these funds.

Thompson warned about competition from conservatives who are interested in using these funds as ‘pay-fors’ on tax policy, which he said Ag Committee Republicans would oppose. “I want these IRA funds in this farm bill,” he said.

Craig said the IRA funds best practices like carbon sequestration, and Pingree said she likes the focus on resilience for healthy soils. They pointed to carbon markets that see the value and lauded Sec. Vilsack’s use of $3 billion in CCC funds for pilot projects that will “help give us better metrics.”

While there is general agreement that most practices on farms improve the planet, the question is – how do the things farmers already do get monetized?

“They are not getting enough credit for their ecosystem services — carbon sequestration, air quality, water quality, filtration of rain. Farmers improve our environment just by farming,” said former State Senator Mike Brubaker. “Is there some way for them to get paid?”

SUSTAINS Act

Thompson said the farm bill does not address this specifically, but legislation passed in 2022 includes the SUSTAINS Act, which he described as “providing a framework for private industry to be involved.”

Corporations and foundations can donate funds to USDA for conservation purposes, like improving technical assistance for more farmers to have access to popular programs like EQIP. He cited a “great return on investment” from Chesapeake Bay Foundation initiatives as an example.

But he pushed back on the Ag Secretary’s use of CCC funds for such purposes because administrations come and go, with their own changing priorities.

“Having certainty going forward is incredibly important,” he said. “Sec. Vilsack wanted to do things by regulation and his interpretation of how CCC funds could be used. He should have come to us (Congress), instead.”

Likewise, concerns were voiced about emerging land use policies at local, county, state and federal levels.

Renewable energy

Asked for their views on traditional and alternative energy, a bipartisan preference emerged for balancing affordable and renewable sources with science, technology and innovation as “pathways for solutions.”

“We need ‘all of the above’ because energy will be a mix for a very long time,” said Pingree. “But we have to stay in this (renewable) dialog.”

Thompson said the ultimate destination of the Farm Show butter sculpture — a digester on a Pennsylvania dairy farm — is a good example of renewable energy produced from cow manure and food waste.

Craig said biofuels through E15 standards are vital for corn and soybean farmers in her district of Minnesota, with new biobased aviation fuel standards an exciting opportunity that U.S. farmers should benefit from, not imported corn from Brazil.

“Our farmers have to be at the forefront of it, we have to get this right,” said Craig. “As Ranking Member, I’ve got to manage my caucus just like GT does as Chairman, to work together for the right solutions, which are probably somewhere in the middle.”

Food security

Questions were also raised about invasive species, animal health, and safeguarding the food supply — especially in regard to inspection of border crossings for invasive pests that threaten all types of agriculture and novel cross-species migration of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI H5N1) in poultry and now dairy operations.

“We have to make sure we keep investing in our laboratories, inspections, and research,” said Thompson.

According to Redding, the Pennsylvania Diagnostic Laboratories System (PADLS) was born out of the poultry industry’s first difficult encounter with avian influenza back in the early 1980s. Today PADLS is instrumental as the state is one of the first to enter the mandatory national bulk milk testing strategy, and has established some protocols credited to the poultry industry.

He stressed the importance of cross-species engagement between Pennsylvania’s top two ag sectors of poultry and dairy, where biosecurity is essential.

“We’re at about 100% of milk representing our nearly 5000 dairy farms, and we’ve not found (H5N1) on the third cycle of testing now,” Redding reported. “The difficulty with a national strategy is finding a model that fits the diversity of all the states.”

Craig said HPAI is a big concern for her home state of Minnesota, which is No. 1 in turkey production and No. 7 in dairy.

They look forward to working with the new U.S. Secretary of Agriculture on what the national strategy looks like going forward “without overburdening the farmers.”

-30-