From whole milk in schools to farm bill to climate-warped food transformation, scientists and lawmakers are getting busy, farmers need to get busy too

In the global anti-animal assault, real science must lock horns with political science and defend American farmers — the climate superheroes that form the basis of our national security. Photo by Sherry Bunting

By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, Jan. 5, 2024

EAST EARL, Pa. – It’s a New Year, and we have new hope on several fronts that are all linked together, in my analysis.

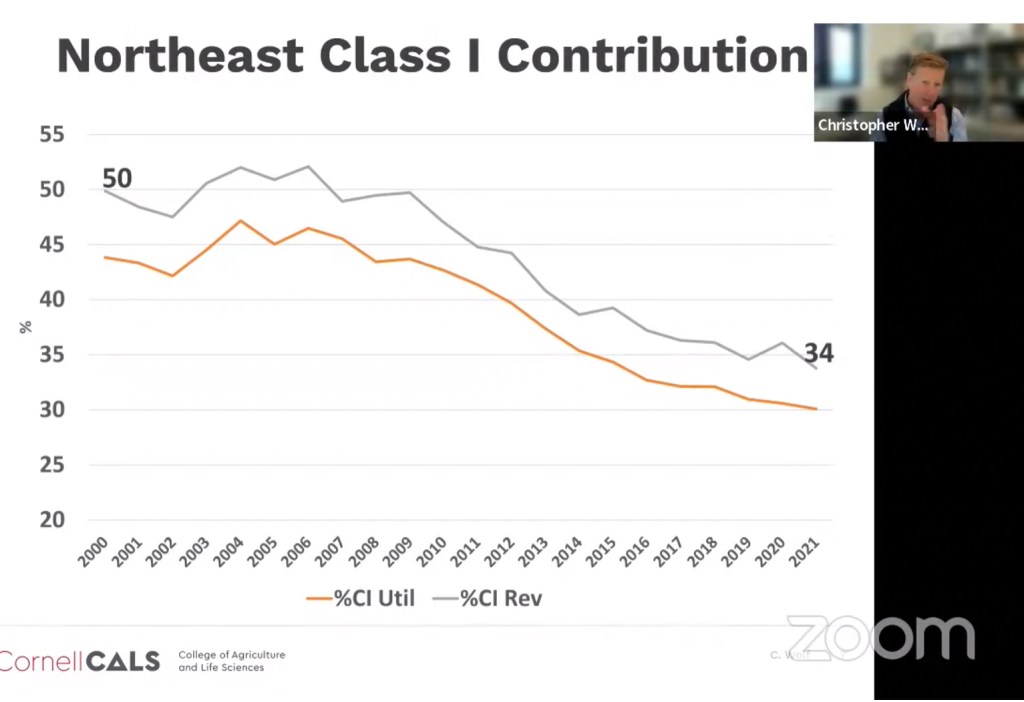

Top 2023 headlines for dairy farmers revolved around dairy markets that underperformed, successes and challenges in the quest to get Whole Milk choice back in schools, a plethora of draft USDA and FDA proposals that dilute real dairy, farm losses and governmental hearings on federal milk pricing, negotiations and extensions for the farm bill, and acceleration of ‘climate-smart’ positives and negatives buckling down for business in an area where political science is trumping real science on the rollercoaster ride ahead.

All of these headlines are inextricably linked. There is a global anti-animal assault underway, but people are wising up to the not-so-hidden agenda that is grounded in climate transitions and food transformation that give more power and control over food to global corporations while diminishing what little power farmers have in Rural America where our national security is at risk.

Real science locks horns with political science

As we head into 2024, a bit of good news is emerging as scientists are mobilizing to defend the nutritional, environmental and social honor of livestock — especially the much-maligned cow.

After an international summit of scientists in October 2022, work has been underway to bring together an international pact.

Dubbed the Dublin Declaration of Scientists, experts around the world have authored and are getting colleagues to sign-on to this document that calls for governments, companies, and NGOs to stop ignoring important scientific arguments when pushing their anti-animal agendas in the name of climate, transformation, and the Global Methane Pledge.

To date, nearly 1200 scientists have signed the Dublin Declaration, aimed foremost at the Irish government’s proposal to slaughter cows to meet methane targets. The Dublin Declaration represents the work of scientists across the globe for a global audience beyond Ireland.

Here in the U.S., we are sitting on the cusp of Scope 3 emissions targets of global milk buyers that have been hastily formulated based on the science of greed, not the science of greenhouse gas emissions. It’s time for the dairy organizations and land grant universities that represent, serve and rely on farmers to drink up on their milk and strengthen their spines.

Farmshine has brought readers the news about what has been happening in Europe, such as in the Netherlands and Ireland, regarding proposed farm seizures and cow slaughter, and the response of farmers there has been to challenge the political establishment.

The U.S. is not far behind. At COP28 recently, American cattle industries were criticized, and even Congressional Ag Leaders are miffed by what they heard.

Still, some of our dairy organizations brag about being at COP26, 27, 28 and taking part. Even the dairy farmers’ own checkoff program is caught flat-footed. They’ve already caved to the Danone’s, the Nestles, the Unilevers, and such.

In fact, DMI’s yearend review touted its increase in U.S. Dairy Stewardship Commitment adopters to 39 companies representing 75% of the milk supply with membership in the Dairy Sustainability Alliance standing at 200 member companies and organizations. But what are they doing with those relationships to STAND UP ON SCIENCE FOR THE COWS?

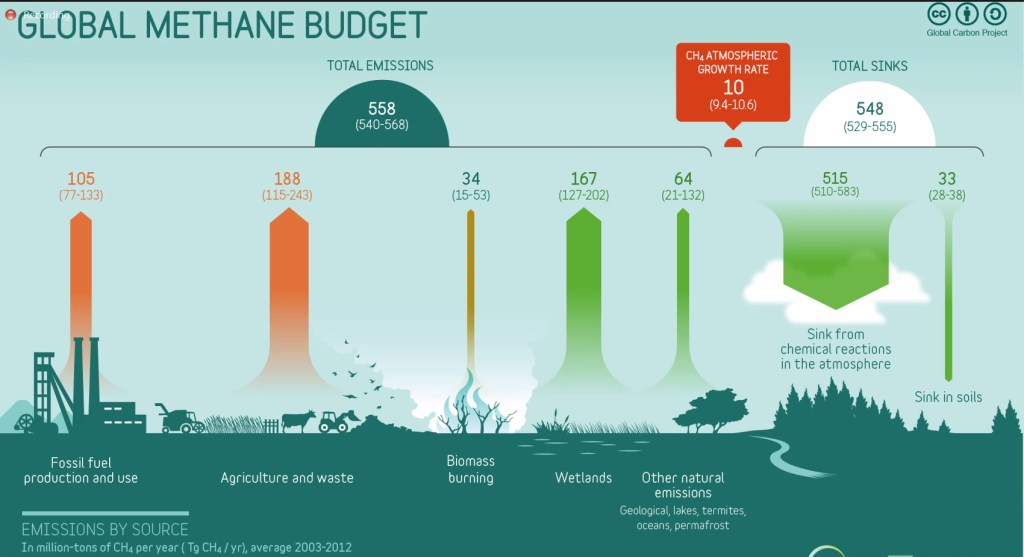

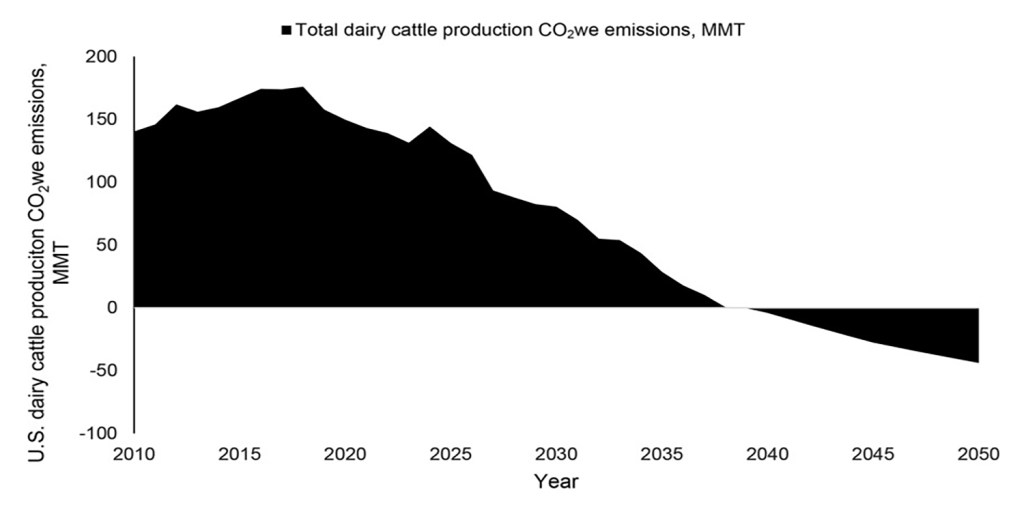

The Stewardship Commitment includes DMI’s Net-Zero Initiative, where the cyclical short-lived nature of methane and the role of cattle in the carbon cycle is still not appropriately accounted for and is one of the points made in the Dublin Declaration of Scientists.

In the U.S. dairy industry, the trend on GHG revolves around DMI’s Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy, which placates large multinational corporations in the development of voluntary programs, telling farmers they are in control with their organizations as a sort of gatekeeper. That is, until those programs become mandatorily enforced by those milk buying corporations, while the science on methane and the cow’s role in the carbon cycle as well as U.S. data vs. global data continue to be ignored when they are sitting in the midst of UN Food Transformation Summits, COP26, 27 and 28, and the WEF at Davos.

In fact, during the annual meeting webinar of American Dairy Coalition in December, U.S. House Ag Chairman G.T. Thompson of Pennsylvania was asked his thoughts on some of the statements that came out of COP28 recently criticizing American dairy and livestock consumption.

“My first response was to find it laughable because it really shows you the difference between political science and real science,” he said. “It’s sad when people are so illiterate about the industry that provides food and fiber that they don’t understand how livestock contribute to carbon sequestration.

“We have a real battle,” Thompson said, adding that those putting out such statements criticizing American livestock “don’t even know which end the methane comes from. The world needs more U.S. farmers and less UN if we want a better world. The facts and the science are on our side. Let’s not let the other side control the narrative.”

Bottomline for Thompson is this: “The American farmers are climate heroes sequestering 10% more carbon that we emit. No one does it better anywhere in the world. Let’s be speaking up and speaking out. We can push it back with the facts and the science. I would encourage each of us to do that and become effective just telling that story,”

In the same ADC webinar in December, Trey Forsythe, professional staff for Senate Ag Committee Ranking Member John Boozman of Arkansas agreed.

“The language coming out of COP28, a likely European-led effort, shows what we are up against from people with no background on the role of dairy and livestock. We have to keep beating that drum on the efficiency of U.S. dairy and livestock farms,” he said.

In the same accord, scientists are getting busy, and we all need to get more involved.

In a dynamic white paper released last year, scientists made 10 critical arguments on this topic of livestock greenhouse gas emissions (GHG). Here’s what the scientists behind the Dublin Declaration are saying and why it’s so important for our land grant university scientists to sign on.

“Livestock agriculture creates GHG emissions, which is a serious challenge for future food systems. However, arguing that climate change mitigation requires a radical dietary transition to either veganism or vegetarianism, or the restriction of meat and dairy consumption to very small amounts is overly simplistic and possibly counterproductive,” the scientists wrote in a recent description of the Dublin Declaration.

“Such reasoning overlooks that dietary change has only a modest impact on fossil fuel-intensive lifestyle budgets, that enteric methane is part of a natural carbon cycle and has different global warming kinetics than CO2, that the rewilding of agricultural land would generate its own emissions and that afforestation comes with many limitations, that global data should not be generalized to evaluate local contexts, that there are still ample opportunities to improve livestock efficiency, that livestock not only emit but also sequester carbon, and that foods should be compared based on nutritional value. Such calls for nuance are often ignored by those arguing for a shift to plant-based diets,” they continued, listing these 10 Arguments with scientific explanations for each one.

Here is how the growing number of international scientists, including Dr. Frank Mitloehner of UC-Davis, situate the problem:

Argument 1 – Global data should not be used to evaluate local contexts

Argument 2 – Further mitigation is possible and ongoing

Argument 3 – Only a relatively small gain can be obtained from restricting animal source foods

Argument 4 – Dietary focus distracts from more impactful interventions

Argument 5 – Nutritional quality should not be overlooked when comparing foods

Argument 6 – Co-product benefits of livestock agriculture should be accounted for

Argument 7 – Livestock farming also sequesters carbon, partially offsetting its emissions

Argument 8 – Rewilding comes with its own climate impact

Argument 9 – Large-scale afforestation of grasslands is not a panacea

Argument 10 – Methane should be evaluated differently than CO2

These arguments take nothing away from the technologies that are being developed to help dairy and livestock producers further reduce emissions and sequester carbon. Technology has a role in amplifying the cow’s position as a solution, not to cure a problem she does not have! And farmers deserve to get credit for what they’ve already achieved.

Farm, food, and national security interdependent

The 2018 Farm Bill was extended for another year at the end of 2023, but the urgency to complete a new one continues as a big priority for House Ag Committee Chairman G.T. Thompson. In the recent ADC annual meeting webinar, he said: “You don’t want us writing farm bill legislation — or any legislation — just listening to voices inside the Beltway in Washington. It would not work out well.”

He thanked and encouraged farmers for being part of the process, saying there’s more to do.

“We’re building this farm bill listening to your voices, the voices of those who produce, those who process, and those who consume — all around the country,” said Thompson, noting nearly 40 states were visited for nearly 80 listening sessions over 2.5 years on the House side.

“This farm bill is about farm security. It’s about food security. And it’s about national security – all three of those are interdependent,” he added.

The extension and funding of the current farm bill for another year — while Congress works on the new one — means programs like Dairy Margin Coverage will continue for 2024, but the enrollment announcement has not yet been made by USDA.

In past years, the enrollment began in October of the previous year and ended at the end of January for that program year. When DMC first replaced the precursor MPP, enrollment was announced late and continued into March of the first program year (2019). At that time, farms could sign up for five years through 2023 or do it annually.

In 2023, DMC paid out a total of $1.27 billion in DMC payments for the first 10 months of the year.

Chairman Thompson noted that effective farm policy is the key, and the extension means no disruptions, he said: “We attached good data for dairy with policy changes, including for DMC, and some positive changes for the nutrition title within the debt ceiling discussion.”

On DMC, the supplemental production history was added in the legislation extending the current farm bill that was signed by the President at the end of November.

“It provides our dairy farmers the certainty that their additional production will be covered moving forward,” Thompson confirmed, adding that they are looking at moving up the tier one cap to be more reflective of the industry.

The farm bill is also being crafted to use no new tax dollars by reworking priorities, looking at the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) funds, administrative funds and shoring up funds from the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) priorities to secure the farm bill baseline for the future.

The $20 billion in IRA funds being thrown about for conservation and environmental programs as well as ‘climate-smart’ grants is already down to $15 billion without spending a dime because of how it is designed to phase down and go away in 2031 and the fact that USDA is believed to not have the authority to keep these funds outside of the farm bill, Thompson explained. Negotiations are considering bringing this into the farm bill baseline so that it is there – and used for farmers – now and in the future.

“(The IRA) is not a victory if agriculture does not get the full benefit of these dollars. We can make that happen in this farm bill,” said Thompson. “Reinvesting the IRA dollars into the farm bill baseline will allow us to perpetually fund conservation in the future.”

Conservation programs are historically oversubscribed and underfunded.

Thompson expects crafting and advancing of the next farm bill to continue in earnest. He hopes to have a chairman’s mark of the bill released by the end of January and have it before the House by the end of February. Much of this timeline depends on House leadership, and the Senate has its own time frame, said Thompson.

He urged dairy farmers to spread the word to their members of Congress that farm security and food security are national security.

He also noted that the nutrition title had some of its toughest elements ironed out during the continuing resolution process in which the farm bill was extended.

“I’ve managed this in such a way that we’ve accomplished already the hard things in that title,” said Thompson.

Deploying dairy farmers on legislative efforts

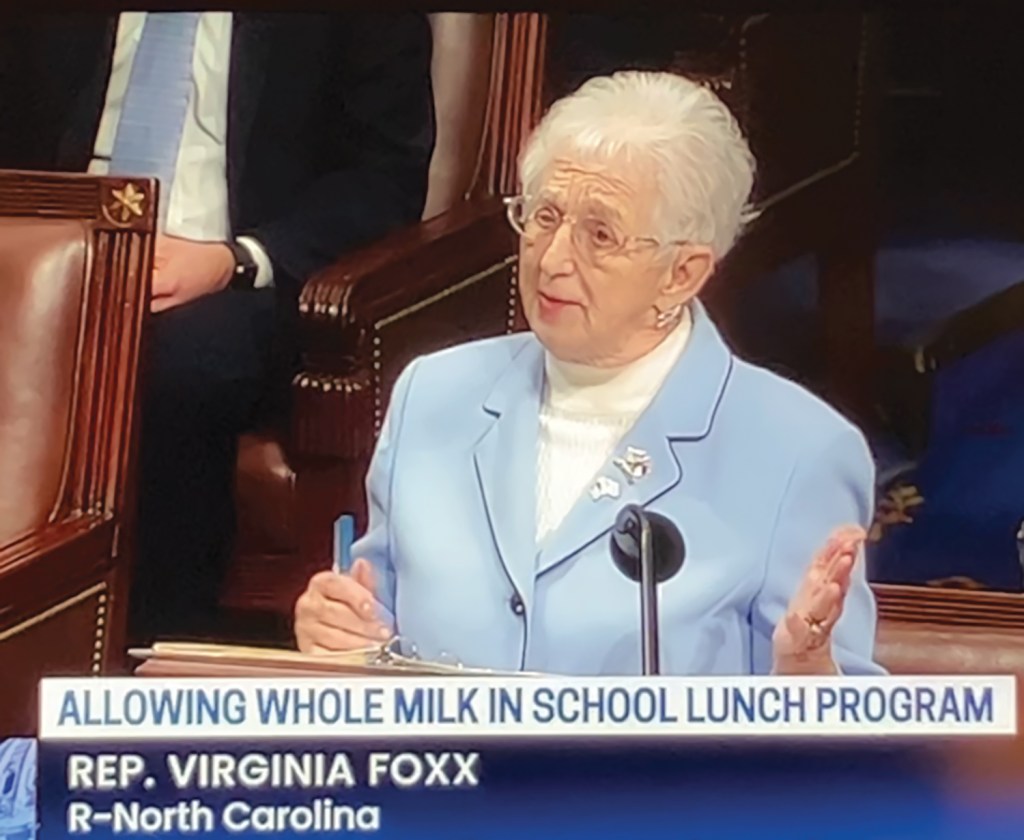

“Passage of the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act is good for kids good for the dairy industry, and good for the economy. It simply restores the option, the choice, of whole milk and flavored whole milk, and holds harmless our hardworking school cafeteria folks by making sure the milkfat does not count toward the meal recipe limitations,” Thompson reported.

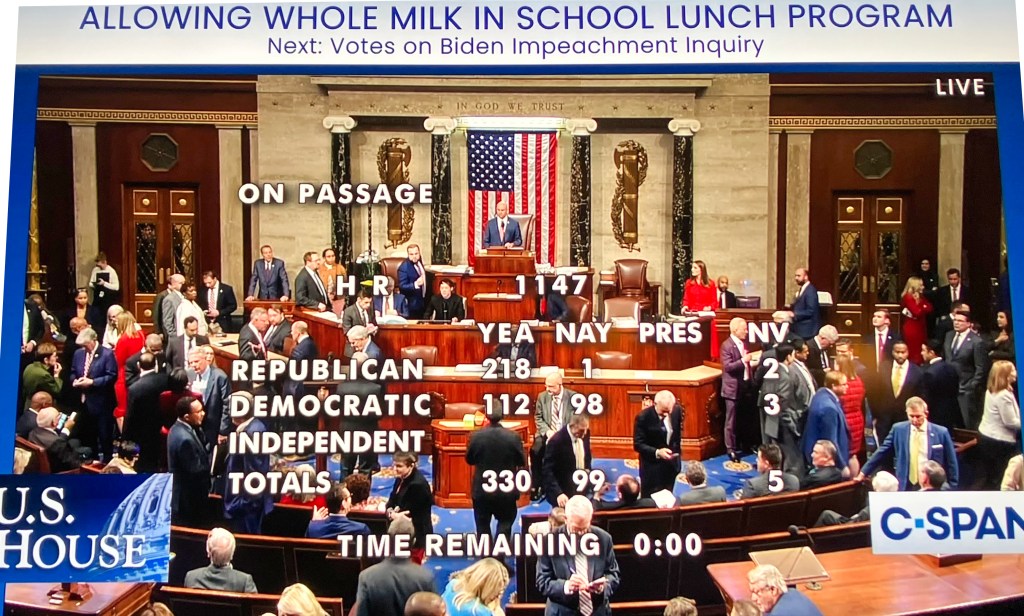

He wanted well over 300 votes for H.R. 1147 in the House to send a strong message to the Senate. On Dec. 13, the House gave him 330 ‘yes’ votes for Whole Milk for Healthy Kids.

“I would like to deploy you now on the Senate. The bill in the Senate (S. 1957) has the same language and it is tri-partisan with Republican Senator Roger Marshall, a medical doctor, Democrat Peter Welch and Independent Angus King as original sponsors,” said Thompson to dairy farmers gathered virtually for the ADC annual meeting webinar.

“There are other co-sponsors as well (12), and from my state of Pennsylvania, Senator John Fetterman is a cosponsor. Our other Senator (Bob Casey, Jr.) has not cosponsored and seems to be in opposition to it,” he said. “We need you to weigh in with your senators that this is about nutrition and health of our kids and the health of our rural communities. You are in a good position to tell the story of what happened in 2010 when fat was taken out of the milk in schools.”

Thompson noted that, “As you are doing that, you are developing relationships that will help us in the farm bill also. On the farm bill, talk about return on investment, the number of jobs and economic activity and taxes from agribusinesses, about the food security and national security and environmental benefits, science, technology and innovation in agriculture,” he said.

“Less than 1.75% of what we spend nationally is the farm bill. That’s a big return on investment, again, for food security and national security.”

Questioned about the milk labeling bill of Pennsylvania Congressman John Joyce, a doctor, Thompson said it is a strong bill. He confessed his dismay with USDA caving on this question and called FDA “a problem child” on milk labeling.

“This bill is not self-serving for dairy. This is about consumers having the information to make proper decisions on their nutrition,” he said.

To be continued