Fluid milk sales are up, Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act is moving. Meanwhile industry globalists put big bets on ESL, shelf-stable, with favor from Vilsack

By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, October 18, 2024

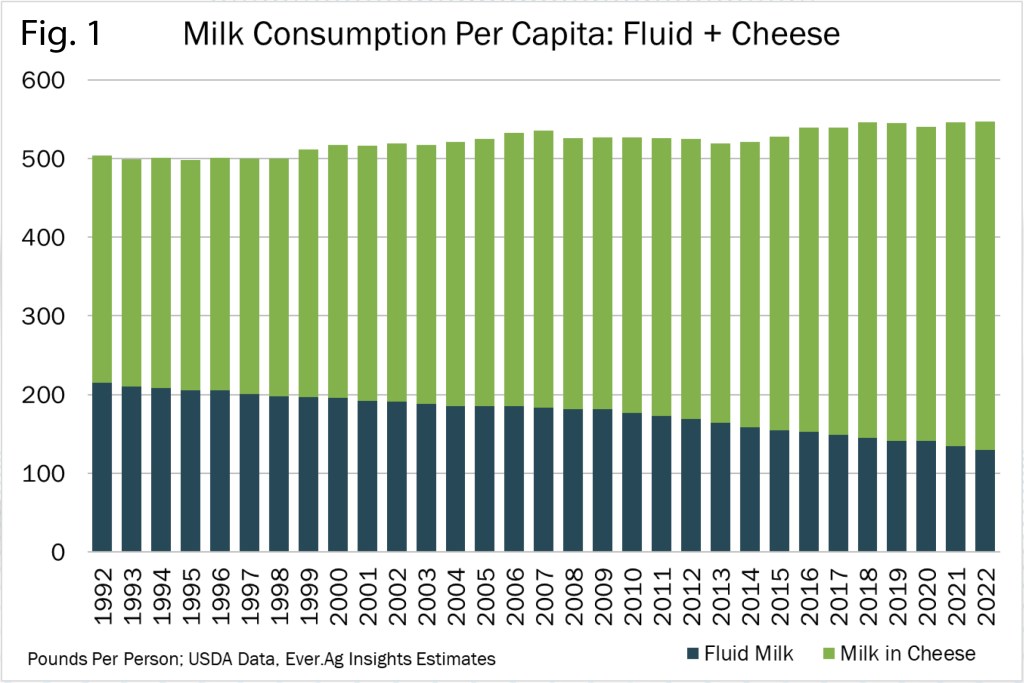

EAST EARL, Pa. — Protein is all the rage right now, and consumers are turning back to real milk as they realize its natural high quality protein benefits. Year-to-date fluid milk sales continue to outpace year ago, and that’s good news. Here are some key factors in the future of fluid milk in the U.S.

Fluid milk sales up!

July’s total packaged fluid milk sales more than recovered the June slump — in a big way, and August looks promising too.

USDA estimated packaged fluid milk sales at 3.4 billion pounds in July, up 4.3% year-on-year (YOY). This amplifies the pivotal year-to-date trend above year ago for the first time in decades (except the 2020 pandemic year).

Specifically, USDA’s Estimated Fluid Milk Product Sales Report for July, released in late September, noted conventional fluid milk sales total 3.7% higher YOY, with organic up 11.7%.

Conventional unflavored whole milk sales were up 4.7% YOY in July, while organic whole milk sales were up 17.1%.

Flavored whole milk sales were mixed because these sales rely upon what processors are willing to make and offer on store shelves, not necessarily reflecting what consumers want to buy. When fewer packages of whole flavored milk are offered, the full potential of sales are restrained.

Year-to-date (YTD) sales of all fluid milk products for the first seven months of 2024, at 24.7 billion pounds, are up 0.7% YOY, adjusted for Leap Year. Of this, YTD conventional whole milk sales for the first seven months of 2024, at 8.8 billion pounds, are up 2.1% and organic whole milk sales at 914 million pounds are up 12.6%.

The August report to be released in the coming weeks is shaping up similarly. August Class I utilization pounds reported last week by USDA are up 1.1% YOY and 1.1% YTD (Jan-Aug).

Making more fat, importing it too?

Meanwhile, the monthly World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) released Oct. 9 reduced its milk price forecasts for the rest of 2024 and into 2025, expecting Class III prices to fall from September highs as cheese price declines are expected to more than offset the higher whey prices.

This report is looking at all the major new cheese capacity coming online in the next 12 months, which is expected to saturate the cheese market to drive prices lower so that U.S. cheese makers can be globally competitive and continue exporting record amounts of cheese.

But is the milk available to do this? Likely not without robbing from Classes I, II and IV channels. Still, the WASDE forecasts lower Class IV prices also due to the abruptly declining butter price being only partially offset by the higher nonfat dry milk prices.

In short, dairy farms are making higher-fat milk, and the food industry is importing more milkfat, especially in the form of whole milk powder. WMP imports have been up by a record amount YOY in each of the past four years, especially 2024.

Restoring whole milk choice for kids!

Now would be a particularly good time for whole milk choice to be restored in our nation’s schools since we apparently have too much milkfat and not enough skim. Given this scenario, how can anyone in this industry still believe the whole milk in schools would hurt the industry’s ability to make enough butter and cheese.

Unless it is excess butter and cheese that is needed to push prices down in order to continue beating record exports at reduced prices paid to farmers.

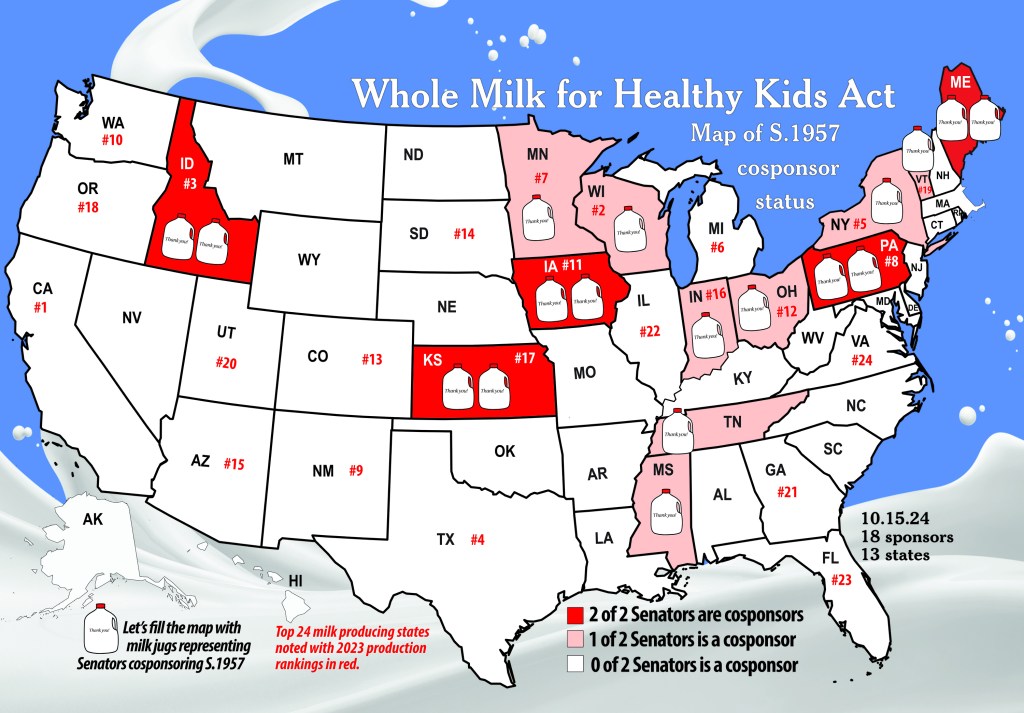

Getting whole milk choice into schools would help. IDFA has been touting the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act. NMPF says they are on board too. This means the industry is united, right?

What are the chances that GT Thompson’s bill to bring whole milk choice back to schools will finally make it all the way to the President’s desk?

For starters, it passed the House by an overwhelming bipartisan majority last December. The Senate bill, S. 1957, has 11 Republicans, one Independent and five Democrats signed on, including notable Democrats such as Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, Peter Welch of Vermont, Kirsten Gillibrand of New York, and John Fetterman of Pennsylvania who chairs the Senate Ag Subcommittee on Nutrition.

The main sponsor is Republican Senator Roger Marshall of Kansas, a doctor. States represented are Pennsylvania, Vermont, Wisconsin, Idaho, New York, Iowa, Ohio, Indiana, Tennessee, Maine, and Mississippi.

In fact, Pennsylvania now has both Senators signed on. Senator Bob Casey Jr. (D-Pa.) is late to the party, but he has finally signed on as a cosponsor of S. 1957 on Sept. 19. It’s nice to see both senatorial milk jugs filled on the map for the Keystone State, but the bill needs more cosigners to fend off the blockade by Senate Ag chairwoman Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.).

GT has included the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act in the House Ag Committee-passed farm bill. Word from Washington over the past few weeks is that a new farm bill is expected to get done after the elections in the lame duck session, and that GT will fight to keep the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act in the bill. Let’s hope so.

USDA: two movers for Class I?

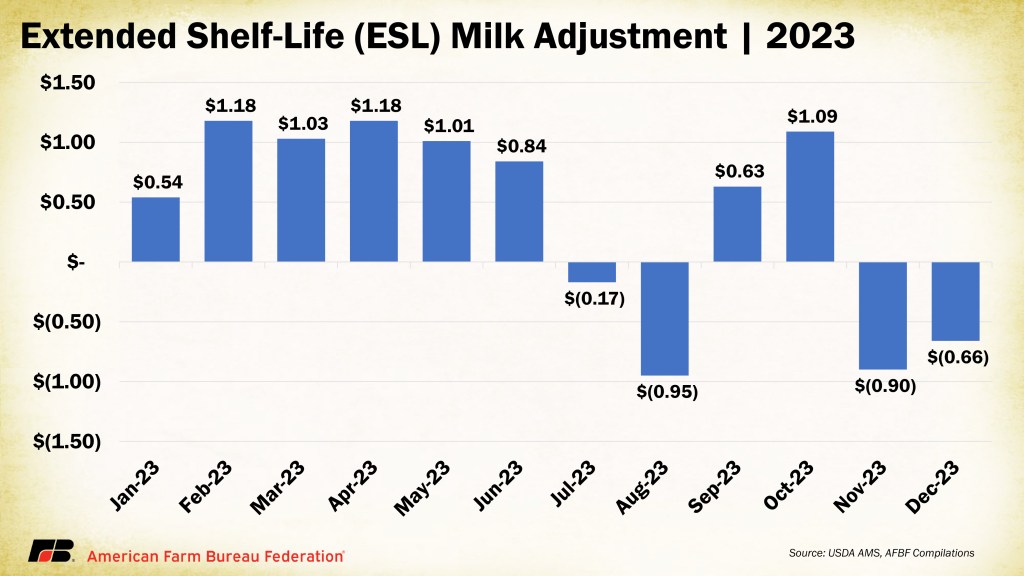

Also related to Class I fluid milk sales, the dairy industry awaits a final decision on USDA’s proposed changes to federal milk pricing formulas, which includes a surprise for fluid milk: splitting the baby and adding a fifth class of milk in the form of two Class I mover announcements each month.

The hearing record is woefully inadequate. No proposal. No evidence. No testimony. No analysis. No parameters. No definition. Even USDA’s own static analysis shows these two movers would be as much as $1 or more apart in any given month.

Fresh, conventionally processed (HTST) milk would go back to being priced by the the higher of the Class III or IV advance pricing factors to determine the Class I skim milk base price portion of the mover.

However, milk used to make extended shelf life (ESL) fluid milk products, defined only as “good for 60 days or more,” would continue to be priced using the average of these two pricing factors, plus-or-minus a rolling adjuster of the difference between the higher-of and average-of for 24 months, with a 12-month lag.

With two movers, fluid milk costs could be different for plants in the same location based on shelf life, with no clear definition for the new class, nor parameters established to qualify. Could we see label changes to move between movers?

Processors will know the rolling adjuster 12 months in advance, due to the “lag.” They will know the two advance-priced calculations (higher-of and average-of) a month in advance. They will have it charted in an algorithm no doubt and make decisions accordingly.

Farmers, on the other hand, will find out how their milk was used and priced two weeks after all their milk for the month was shipped. Those milk checks will be even less transparent than they are now.

Big bets on ESL, shelf stable

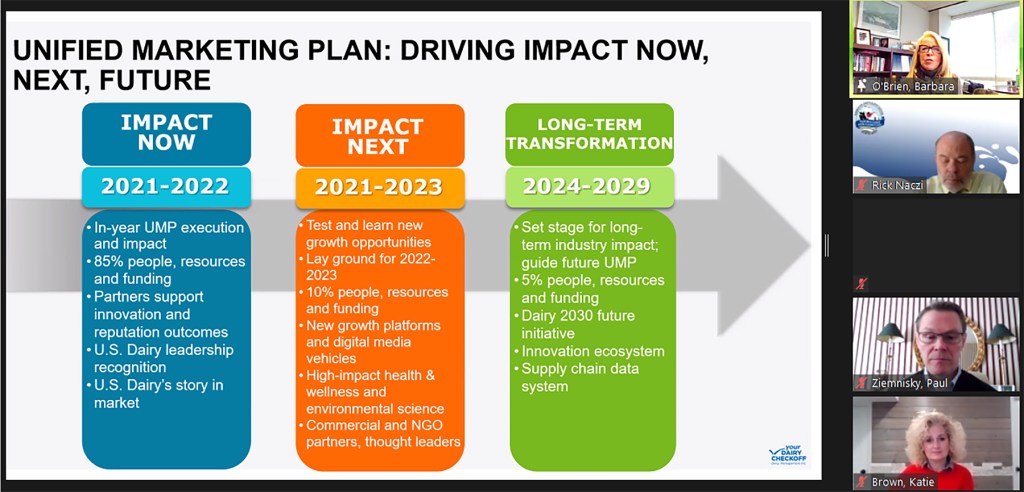

The dairy checkoff has openly identified ESL, especially shelf stable aseptically packaged milk, as its “new milk beverage platform,” using dairy farmer funds to research and promote it and to study and show how consumers can be “taught” to accept it.

The whole deal is driven by the net-zero sustainability targets. So, follow the money.

Dr. Michael Dykes of IDFA, at the Georgia Dairy Conference in January 2024, told dairy producers that “this is the direction we (processors) are moving… to get to some economies of scale and bring margin back to the business.”

He said the planned new fluid milk processing capacity investments are largely ultra-filtered, aseptic, and ESL — 10 of the 11 new fluid plants on the IDFA map he displayed are ESL. Some will also make ultrafiltered milk, and some will make plant-based beverages also.

Meanwhile, the linchpin of regional dairy systems is conventionally pasteurized (HTST) fluid milk, prized as the freshest, least processed, most regionally local food at the supermarket.

To be sure, this two-mover proposal fits the climate and export goals set forth by the current Ag Secretary Tom Vilsack when he was working as the highest paid dairy checkoff executive in between the Obama and Biden administrations.

The pathway to rapidly consolidate the dairy industry to meet those goals is to tilt the table against fresh fluid milk, something he already put a big dent in when removing whole milk from schools.

They decided thou shalt drink low-fat milk and like it. Apparently, they are equally convinced about ESL / shelf stable milk as the way of the future and will continue using mandatory farmer checkoff funds to figure out how to get consumers to like that too.

Just this week, the food writer for The Atlantic did a piece on shelf-stable milk, calling it “a miracle of food science” and lamenting in her Op-Ed that it’s a product “Americans just can’t learn to love.”

Author Ellen Cushing took jabs at America’s preference for fresh natural milk from a global perspective, without a thought for the local dairy farms and regional food systems that are tied to fresh milk. She states that by worldwide standards, other countries have gone shelf-stable milk, which she describes as “one of the world’s most consumed, most convenient and least wasteful types of dairy.”

Processors are making big bets on consumer conversion to ESL and shelf-stable. There are cards to play in every hand. TO BE CONTINUED!

-30-