As bird flu detections escalate among California dairy and poultry operations, Pennsylvania’s State Vet urges early detection to ‘stamp it out’

By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, Nov. 15, 2024

HARRISBURG, Pa. – USDA is set to amend the spring order on transportation testing to include a new National Bulk Milk Testing (NBMT) program for H5N1 in dairy cattle, which will be patterned off the former Brucellosis strategy.

This will be a regionally tiered approach, testing samples from processing plants, to assess where the virus is at this time, according to Dr. Kellie Hough, USDA District Emergency Coordinator.

“Depending on the results, we will then drill down to the state level and to the farm level, if necessary, to attempt to eradicate this,” she said.

Federal and state agencies will work with affected facilities to enhance their biosecurity levels and restrict animal movements, but also to ensure their business continuity.

The federal action is in addition to the ongoing voluntary multi-state silo milk testing surveillance program that Pennsylvania is participating in already. In that program, processors provide blinded samples from bulk milk silos, according to their own cadence of frequency, said Pennsylvania State Veterinarian Alex Hamberg.

Hough and Hamberg gave updates on the Center for Dairy Excellence monthly industry call Nov. 13.

“We supply processors with everything they need to send these samples, and the only information going to the NVSL network laboratory is the date of sample collection and the states represented by the milk in the silo at the time of the sample collection. This helps show we are clear of the virus and helps build a baseline,” said Hamberg.

He said states are having ongoing discussions with USDA about what federal surveillance will look like under the NBMT.

He stressed that the virus can be found in milk samples two to three weeks before clinical infection.

“If we can identify every farm infected right now, then we can contain this thing right now and make this virus extinct to never be seen again,” Hamberg urged. “But if we continue to avoid early identification, we could be stuck with it for as long as it wants to stick around.”

Dairy farmers have been slow to sign on to voluntary bulk tank testing at the farm level, with only 69 herds enrolled nationally, six in Pennsylvania.

Mandatory testing is currently being done in Massachusetts, Colorado, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and California. For the latter, it only began after the spread of H5N1 had escalated among dairy herds and poultry flocks in California.

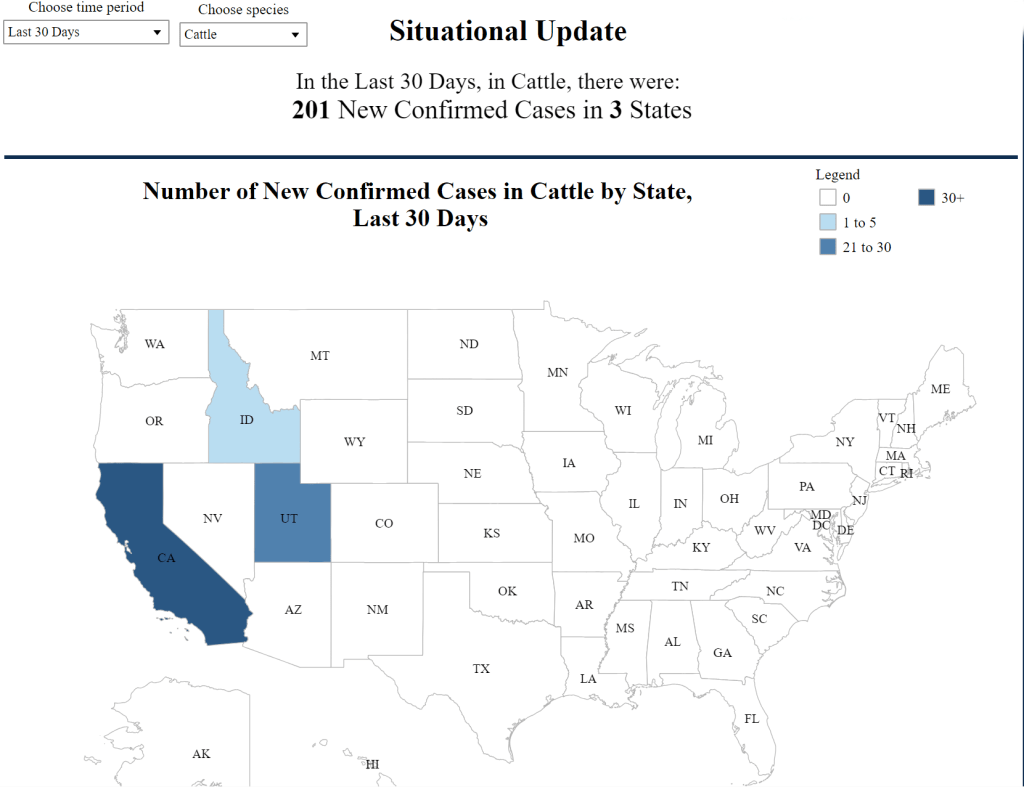

During the past 30 days, as of Nov. 14, there are 201 new herd detections of H5N1 nationally. Of those, 186 were in California, two in Idaho, and 13 in Utah. The Golden State has had H5N1 detections in 291 dairies to-date, with more tests pending, and this represents more than half of the 505 cases across 15 states since the start of the outbreak in Texas last March.

Hamberg said dairies saw a 50% herd turnover within three months of infection in states that have contended with H5N1 in cattle. This is presumed to be a combination of cattle culling as well as some mortalities. Owners of infected herds also report struggling to regain their prior herd production per cow and seeing prolonged elevation in somatic cell counts.

“They are getting slammed in California,” said Hamberg. “It is not a good situation. The dairy industry is suffering, and the poultry industry is suffering. If they had had good participation in voluntary testing beforehand, they may have been able to stamp it out before it spread like this.”

He sees this as particularly important for dairies to consider the voluntary bulk tank testing that gives them ‘monitored herd status’ in Pennsylvania. “Our state is more dense than California, where it is spreading like wildfire,” he said. “In Lancaster County we have dairy on top of dairy on top of poultry on top of pigs. If we find this in an early stage, we can stamp it out quickly and contain it before it spreads all over the place.”

There is no evidence yet that the dairy variant of H5N1 has taken up residence in migratory bird populations or any other wildlife reservoir, but the cattle strain is being found in domestic poultry flocks.

On the human side, Dr. Miriam Wamsley, Pennsylvania Department of Health Epidemiologist reported there have been 36 confirmed human cases across the U.S. of the H5N1 strain found in cattle. Some have been dairy workers, others poultry workers. The cases have been mild, marked by conjunctivitis (pinkeye).

Blood samples collected from workers recently in Michigan and Colorado showed employees previously had it without knowing it.

Wamsley, urged seasonal flu shots, especially for anyone exposed to cattle and poultry: “Flu season is here. If you would contract them simultaneously, there is the possibility of the two (viruses) mixing in the human body to create a new strain, and at the same time, the combination can make a person very sick.”

The recent news of a teenager in British Columbia, Canada, hospitalized in critical condition, as well as the first pig detected with bird flu in Oregon, were confirmed to have the strain that is active in migratory bird populations, not the dairy variant.

Hough reported that USDA is clearing the path to test four vaccine candidates for dairy cattle.

The USDA and FDA have confirmed that there is no threat to human health and that milk and dairy products are safe to consume.

-30-