Farmers testify, Farm Bureau stands firm, USDA asks good questions, wants to hear from farmers

Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, September 22, 2023

CARMEL, Ind. – The controversial “make allowances” took center stage for the past 10 days at the USDA federal milk price hearing in Carmel, Indiana. Witness testimony and attorney cross examinations — as well as follow up questions by USDA staff — have been particularly revealing. To-date there are nearly 300 exhibits, and the hearing is two-thirds of the way through its 21 proposals in five categories. The hearing can be followed daily at the live stream link: https://www.zoomgov.com/j/1604805748

American Farm Bureau Federation economists Danny Munch and Roger Cryan have been exemplary in the way they are bringing their grassroots policy to the USDA hearing setting and standing up to heavy cross examination by attorneys for the processors as they seek to undermine AFBF’s position that no make allowance increases should be granted by USDA without a mandatory, audited cost survey, and that the Class I mover should go back to the ‘higher of’ calculation.

Entering its fifth week on Tues., Sept. 19, the emphasis has shifted to the various proposals on how to calculate the Class I base price ‘mover’ – whether to return to the ‘higher of’ or to use one of several proposals from processor groups that want to keep the ‘average of’ method but propose complicated ‘look-back’ adjusters to incrementally ‘pay back’ future Class I value losses incurred by farmers over a distant multi-year time frame.

Last Friday, September 15, several dairy farmers testified. In this week’s hearing update, we’ll focus on one farmer’s illustrative testimony in support of National Milk Producers Federation’s proposal 13 to return to the ‘higher of’ for the Class I mover calculation.

While several testified, it was dairy farmer Bryan Henrichs, of Breeze, Illinois who best described the impact of the Class I mover change made legislatively five years ago on farmers’ ability to do risk management and on the FMMO mandate for ‘orderly marketing’ and service of the Class I fluid milk markets.

“With some classes having the ability to depool, this has created disorderly marketing as there isn’t the incentive to serve the Class I market,” said Henrichs. “I am unable to have my cooperative depool my milk due to my milk serving the Class I market. I have heard from some in the industry that the negative Producer Price Differentials (PPDs) (and resulting losses to dairy farmers) were caused by the USDA food box program. I would disagree as the negative PPDs began not too long after the industry moved to the ‘average of’ in May 2019.”

Henrichs operates a 300-cow dairy farm, is on the Prairie Farms board, the American Dairy Coalition board, and was part of the American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) dairy task force. He saw first hand the devastating consequences to farmers from the Class I pricing change.

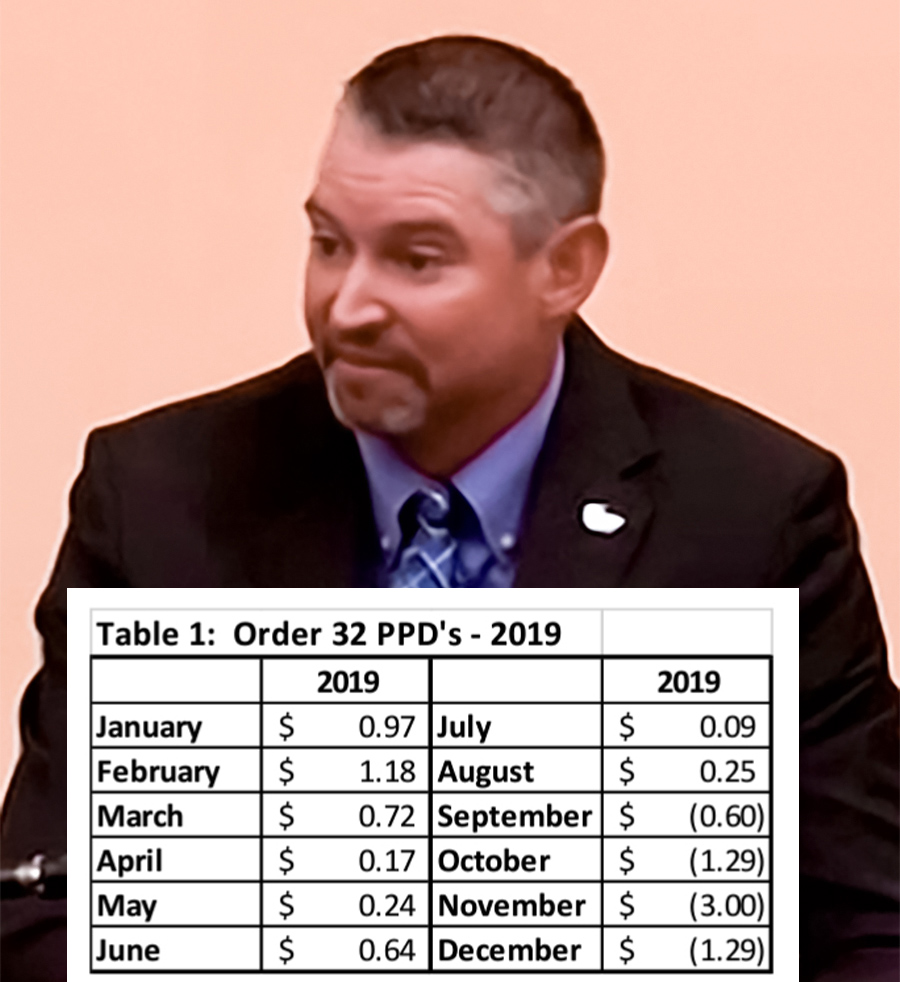

Henrichs included a chart in his testimony showing these PPD swings in his milk marketing area (Order 32) from January through December 2019, before and after the Class I mover change a year before the pandemic hit.

He noted the industry has well documented the severity of losses much larger than this during the 2020-21 pandemic as well as the continuation of Class I value losses and depooling to farmers, even when it doesn’t show up as negative PPD — when Class IV is higher than Class III as has been the case in 2022 and 2023.

Henrichs expressed appreciation to USDA for the Pandemic Market Volatility Adjustment Program (PMVAP) payments that were aimed at covering just a fraction of these losses.

However, Henrichs duly noted the problem with “support” after-the-fact and the problem with “rolling adjusters” that try to make up for these losses later. They don’t help much if the large losses — the large negative basis that can’t be managed — hits cash flow so hard that farms are out of business by the time it’s “made up” to them and then only “made up” partly or quite gradually.

“I know some dairy producers that needed that money at that time — not 12 to 18 months later. I know of some that are no longer in business when they received the (PMVAP) payments,” said Henrichs. “The ‘higher of’ will ensure that the dairy producer is compensated at the time of the sale instead of later by some other form of support… and I worry if the USDA will always have the funds to provide such support.”

Henrichs pointed out that risk management doesn’t help in this scenario.

“We have used risk management tools in the past such as forward-contracting and DRP to help manage the price volatility of the dairy markets. With the ‘average of,’ we see the higher level of negative PPDs, which acts as ‘negative basis’,” Henrichs testified.

“We are familiar with ‘negative basis’ with corn as that indicates what the market values the commodity at the time of sale. At least with corn, I can call the elevator and find out what the basis is and decide if I want to ship to market,” he explained, adding that as dairy farmers, “we produce and ship a perishable product. With a negative PPD, we don’t know until two weeks after we are done shipping for the entire month whether or not there is a negative basis.”

Henrichs noted that he was shown a check from a neighbor who forward contracted in July 2020.

“He shared with me his check as he locked in $18.00/cwt. milk in a Class III futures contract. He lost on the futures contract — as he would expect when the market rises — but due to the negative basis or negative PPD, he ended up with a net check of around $9.00/cwt. I continue to evaluate the amount of negative PPDs since going to the ‘average of,’ and I am reluctant to use forward contracting or DRP as part of my farm’s risk management program,” said Henrichs.

He stood his ground as attorney Steve Rosenbaum for IDFA made several attempts to trip him up on cross-examination. Rosenbaum tried to ‘cherry pick’ a few months in 2019 when the ‘average of’ yielded a slightly higher Class I mover compared to what it would have been under the ‘higher of.’

Henrichs’ matter-of-fact answers left the IDFA attorney unable to break him down. Rosenbaum asked if Henrichs had done monthly analysis of the ‘average of’ vs. the ‘higher of’ to see the months when it was positive. Henrichs replied: “Yes, we’re always watching.”

“No one questions, obviously, that when it comes to 2020 and the pandemic, Class III and IV started diverging substantially, and you ended up with less… but do you agree with me that until that happened, you weren’t experiencing this kind of ‘anomalous’ result, were you?” queried attorney Rosenbaum for IDFA.

“Not at that point, but once we started receiving the negative PPDs, they got extremely large, as you can see,” Henrichs replied, referring to Table I in his testimony. “It was way more of the negative than what the positives were prior to that.”

(Table I shows the PPD in Order 32 for all 12 months of 2019 — before and after the Class I formula change, which was implemented in May of 2019. This was a year before the pandemic. In fact, going forward it is still “way more negative than positive.” Farmshine has also been watching this accumulation of over $1 billion in cumulative net losses to farmers across 53 months, a graph that has been updated and published several times in Market Moos.)

Erin Taylor, acting director of USDA AMS Dairy Programs, questioned Henrichs about risk management: “So is this ‘negative basis’ the reason you are not using risk management tools currently?”

“Yes,” Henrichs replied, adding that, “as a custom operator putting silage up for a lot of dairy farmers, a lot of questions on dairy pricing get sent to me. We’ve had producers that bought DRP contracts, and in the months of April, May and June 2020, they were set to receive a pretty large sum, but because of depooling, with around a $20 to $21 Class III price in June of 2020, farmers in our area — because of depooling — were unable to receive that (higher price) in their milk checks, but they were also not able to receive the DRP payments that were set to come to them.

“They were kicked out because the price on the futures was higher than their contract that they purchased – that they bought for an $18 coverage for example – well that $20 (Class III price) kicked them into being above that ($18) they purchased, and they didn’t get a payment. So, even though on the Board of Trade, they may have looked good, that’s not what we received on our dairy farms,” Henrichs shared.

“Because that Class III milk wasn’t pooled?” Taylor picked up his the thought train in the form of a question.

“Yes, In Order 32 only 6% of Class III milk was pooled that month, so our price was around $12 to $13 per hundredweight for our dairy farms, but their contract for ($18) was set to pay them but did not because of that $20 Class III price on the Board of Trade (which became the announced FMMO price that led to Class III depooling).”

(Put simply: That higher price the DRP contract ‘saw’ meant no DRP payment for the farmer, but that price wasn’t realized by the farmer. This is similar to having your barn burn down, and your insurance adjuster saying ‘well, because your neighbor’s barn didn’t burn down or something on paper says your barn should not have burned down, you are not entitled to a payment for your barn that in fact burned down.)

Taylor also asked what disorderly marketing looks like to dairy farmers. Henrichs gave perhaps the best explanation yet on this hearing record. He explained how the upside-down pricing — the misalignments that have been brought on by the switch from ‘higher of’ to ‘average of’ — caused pooled farmers to have ‘uniform prices’ vastly different within miles of each other due to depooling incentives on some Orders.

“Going back to the months of June 2020, and July, we saw large Class III prices, whereas in the ‘average of’, we saw Class I and Class IV were much lower, and you had farmers in Wisconsin, in Order 30, getting $4 a hundredweight more per the FMMO website, on the uniform price. We have producers that are within miles of 30, shipping in FMMO 32, who were $4 different, and their milk was being produced not far from each other. That’s disorderly marketing in my opinion,” said Henrichs.

“When you have guys not wanting to go to a Class I plant because the Class III price is so much higher, that is what I consider disorderly marketing — where you would have people jumping in and out of which product they want to sell their milk to that day because of the pricing disparity amongst the classes. Part of the class pricing in the FMMOs are to stabilize pricing to producers in each Order to be pretty similar.”

“So you’re saying that you see class prices being in typical historical alignment as orderly?” asked Taylor.

“Yes,” said Henrichs.

“Because then the incentive is there to service the Class I plants?” Taylor asked further.

“Yes, service the Class I first… make sure those are full for the fluid industry because they’re not able to store product like the powder and cheese plants,” Henrichs added.

Throughout this hearing, attorneys for IDFA and Milk Innovation Group scoffed at the idea that Class I plants could have any trouble getting milk for fluid use because the country has more than enough milk to go around.

They avoided the question of what does it cost or how do they attract the milk to the Class I plant when the historical alignments are out of whack.

They put forward witnesses from very large international processors saying that the FMMO minimum prices are set too high, that they must be lowered by raising make allowances and keeping the ‘average of’ mover and cutting Class I differentials and all sorts of changes.

They pointed to the dumping of milk this spring in the Central U.S. as proof that FMMO minimum prices are set too high and must be lowered so that processors can pay premiums if they want to and can invest in plant capacity to soak it up so it doesn’t go to the sewer.

USDA’s Taylor went so far as to ask these processor witnesses what other factors affected the milk dumping this spring, what other factors affect milk production growth (in the Central U.S.).

Processor witnesses stammered around on these capacity and innovation questions. They weren’t sure how to answer some of the very direct USDA questions over why they are so fast to make sure every bit of their cost is covered in that make allowance and yet balk at the idea of being asked to account for more of the pricing or value side.

Henrichs is just one example of farmers who are testifying in person on various days or virtually via Zoom on Friday afternoons. It is obvious that USDA AMS personnel want to hear from farmers – what they have to say, how all of this affects them.

Farmers are the only ones who can show up at the hearing venue on any day, let an official know they are there to testify, and be worked into the schedule without sending written testimony or notice ahead of time. USDA merely asks that farmers bring their written testimony with them and make copies to hand out.

Virtual testimony must be pre-registered, but in-person testimony can happen any day.

Those farmers wanting to testify virtually have one more scheduled opportunity on Friday, Sept. 29. To get one of the available slots for that day, go to the hearing page on Monday, Sept. 25 at noon to look for the signup link. Be quick about it, because last Monday, the slots for Sept. 15 filled up within less than two hours. If the hearing continues into October, go to the webpage on subsequent Mondays to sign up for any slots offered on subsequent Fridays.

The hearing page is at https://www.ams.usda.gov/rules-regulations/moa/dairy/hearings/national-fmmo-pricing-hearing

For technical difficulties, email FMMOHearing@usda.gov

USDA’s Taylor brings the department’s questions for every witness. She has done a noteworthy job of this, pressing industry witnesses for details and bringing the deeper levels of farmer testimony to the fore.

Remember, when this is all over, and the t’s are crossed and i’s dotted on a USDA final decision, farmers will vote ‘yes’ to accept these changes or ‘no’ to dissolve their Federal Milk Marketing Order. This means even if co-ops bloc vote for their members, the co-ops and farmers have the final say.

There is an obvious concern among some in the processing sector that the FMMO system could be dissolved. One may believe that processors want the FMMOs to end because more and more of the cheese and other dairy products are being manufactured and sold outside of the FMMO system and outside of the pooling process.

However, processors have an interest in seeing the FMMO system continue because they rely on the pricing data, the benchmarking, and a built-in make allowance.

The existence of FMMOs and those announced prices actually settle Class III and IV milk futures on the CME. Even if processors hedge risk by using dairy product futures contracts — instead of the milk futures contracts — they still rely on the USDA price survey every week that yields an official weighted average price for the four FMMO commodities that are traded on the CME to come up with the weighted average price of those commodities at the end of each month to settle butter, nonfat dry milk, 40-lb block and 500-lb barrel cheese and dry whey futures contracts.

Some argue that the daily CME spot cash markets for these products could be simply used. However, just think what this would mean if the CME became the only market to look to for futures and cash. Milk doesn’t have a real cash market reported every day on the farmer or processing sides like beef and other commodities.

Furthermore farmers ship milk for four to six weeks before ever knowing what they’re going to get paid for what they shipped, or what the basis is going to be. They can’t look at a market and make decisions. They can’t call an elevator. They can’t hold their product for a week or a month… or even a day.

-30-