Final FMMO rule adds more to make allowances, shortens delay on composition updates, restores higher-of, keeps controversial ESL adjuster.

By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, Nov. 15, 2024

WASHINGTON, D.C. – The USDA released on Nov. 12 the Secretary’s nearly 400-page final decision on the Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) price formula changes, with a few changes from the July ruling.

USDA rejected comments seeking to forestall the make allowance increases or to reduce their size. All make allowances are further raised in the final rule vs. preliminary rule by a fraction of a penny for marketing costs. Also, USDA has added more than a penny per pound to its earlier decision on the nonfat dry milk make allowance. These are milk check deductions that are embedded in the class and component formulas.

USDA also plans to stick with its earlier decision to introduce a rolling adjuster for extended shelf life (ESL) milk, which creates essentially two-movers for Class I that was not part of the hearing scope. The Department further defined ESL milk by processing method to be all milk using ultra-pasteurization, not just relying on the shelf life designation of 60 days or more.

The broad range of changes in the proposed final rule are the result of the national hearing and rulemaking process that began in 2023. It will be made final for implementation after dairy producers vote to approve these changes in the Order-by-Order referendum that will be completed before the new administration takes office on January 20th.

USDA AMS will mail voting ballots to eligible producers and qualified cooperative associations — which may bloc-vote on behalf of their eligible members — after the final rule is published soon in the Federal Register. Ballots must be returned with a postmark of December 31, 2024 or earlier and be received by the Department by January 15, 2025 in order to be counted.

Not all producers in a Federal Order will be eligible to vote. Only producers with milk pooled on a Federal Order in the month of January 2024 are eligible to vote in that Federal Order.

A ‘yes’ vote accepts all parts of the final rule. A ‘no’ vote rejects the changes but also rejects the continuation of that Order. Any of the 11 Federal Orders that does not meet the two-thirds majority requirement for acceptance of these changes will be terminated. The two-thirds majority is calculated among eligible producers in the Order who return a ballot.

USDA AMS will host three public webinars to further inform stakeholders of the changes and referendum process on Nov. 19 and Nov. 25 at 11:00 a.m. ET and Nov. 21 at 3:00 p.m. ET. A link to access the webinars will be provided at the AMS hearing website along with supplementary educational documents.

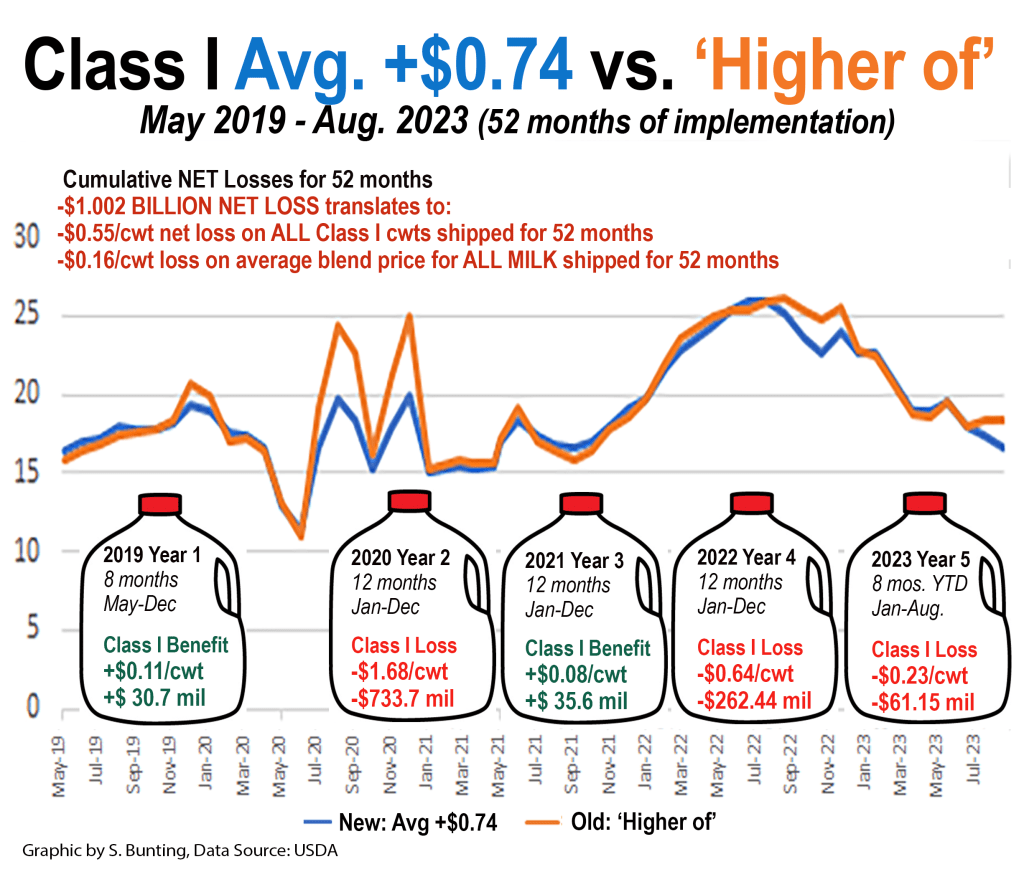

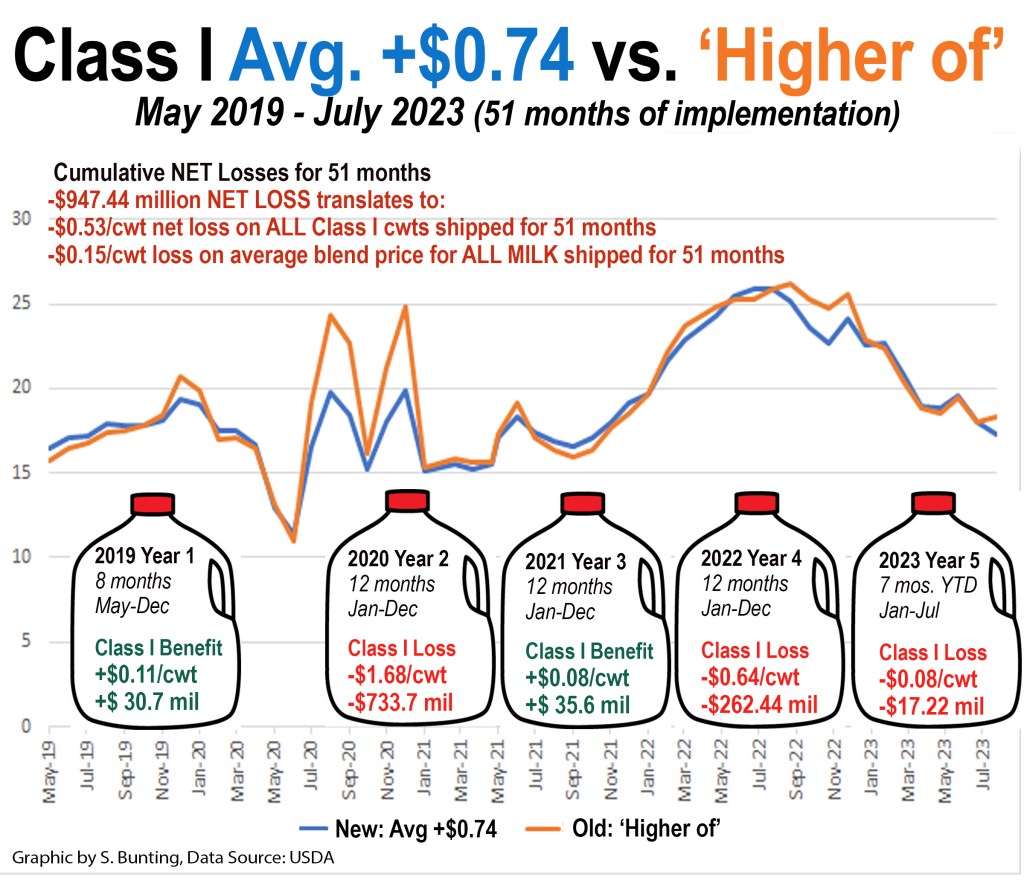

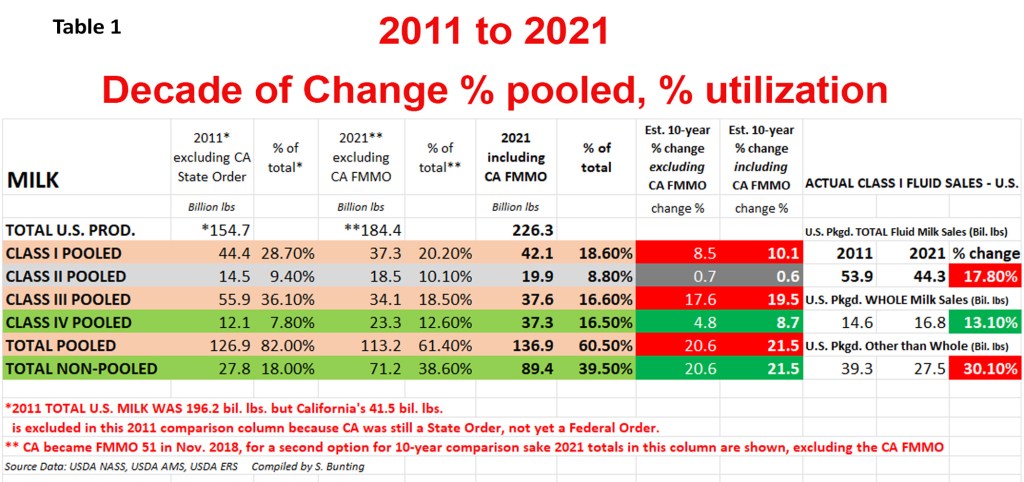

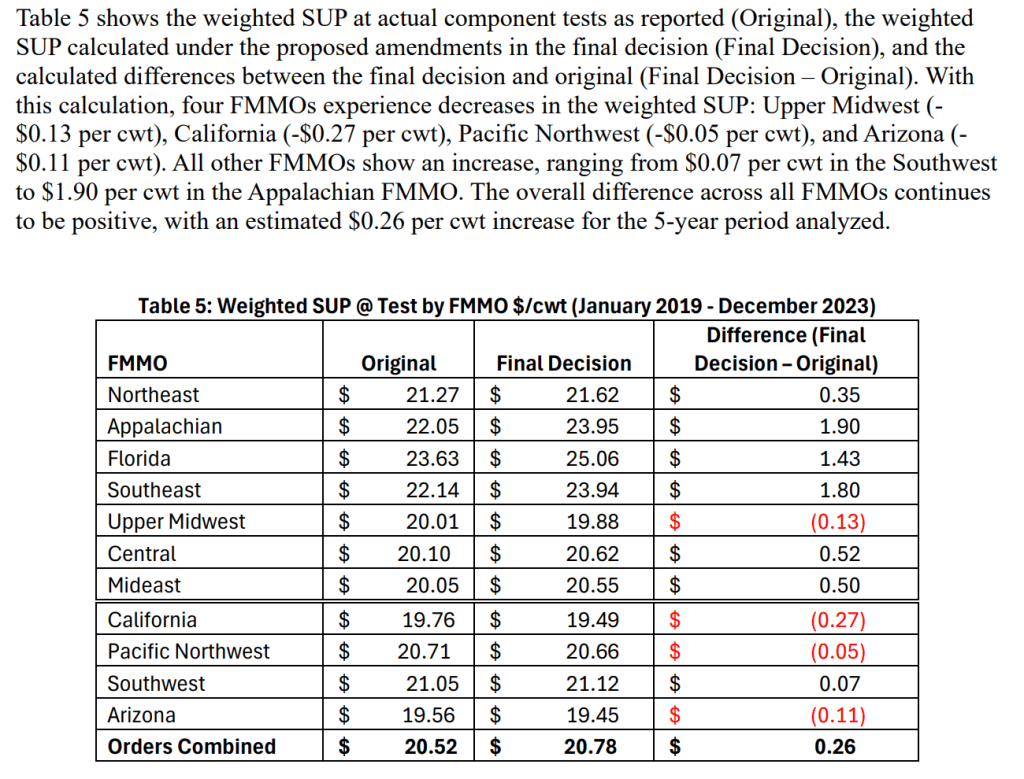

Using its backward-looking analysis of applying the changes to actual 2019-23 pool test data, the combined net benefit for all 11 Federal Orders of all the changes in the final rule is estimated at +$0.26 per hundredweight. However, an average does not tell the full story, and it does not include the positive orderly marketing impact of restoring the higher-of method for calculating the Class I base price mover.

USDA’s Table 5 above is the backward-looking static analysis of the weighted Statistical Uniform Price (SUP) – at actual pool component test – showing net benefits for the following Orders: Appalachian +$1.90 per hundredweight, Southeast +$1.80, Florida +$1.43, Central U.S. +$0.52, Mideast +$0.50, Northeast +$0.35, Southwest +$0.07.

Table 5 shows net-negative impact for California -$0.27, Upper Midwest -$0.13, Arizona -$0.11, and Pacific Northwest -$0.05.

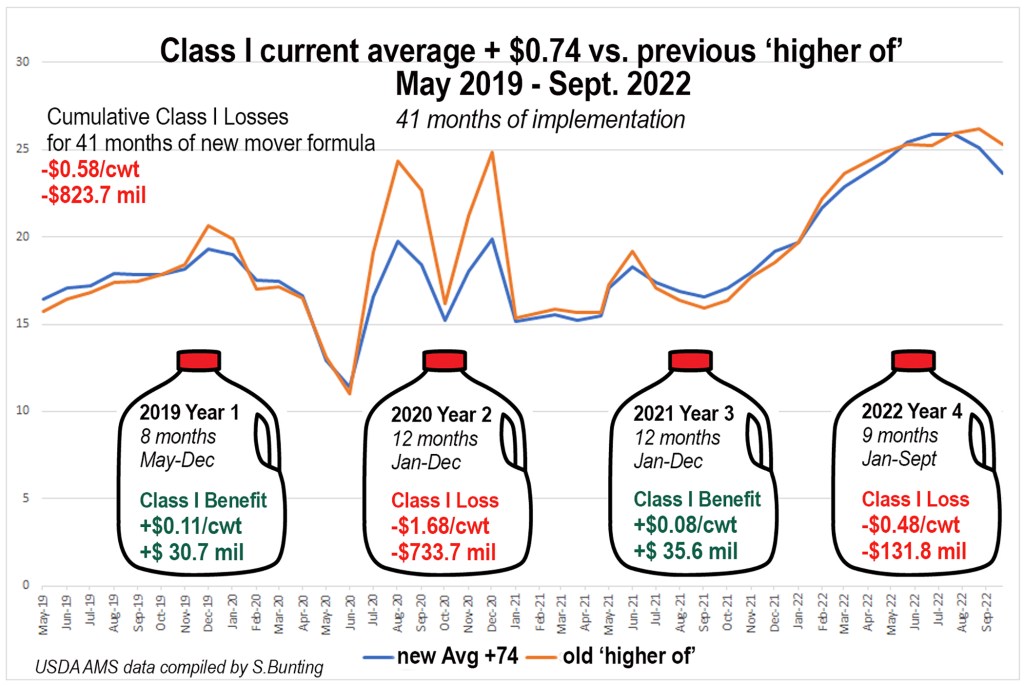

However, this analysis does not factor-in the positive impact of restoring the higher-of method for calculating Class I. The Orders showing net negative impacts above have more liberal policies for jumping in and out of FMMO pools. Since USDA did not quantify the benefit of its restoration of the higher-of method for the Class I mover, it’s important to note that this can soften the blow.

According to experts consulted by Farmshine on this matter, the potential average benefit for the same 2019-23 period of orderly marketing under the higher-of method in a low-Class-I FMMO like the Upper Midwest is 7 to 10 cents per hundredweight.

More importantly, the orderly marketing restored by this part of the final rule has a protective effect on the month-to-month hits taken by pooled producers from opportunistic depooling and negative PPDs. Why? Because the higher-of method — used for two decades, before the legislative change in 2019 — encourages functional class price relationships that promote orderly marketing.

In short, producers should realize that the restoration of the higher-of reduces the prevalence of very large negative PPDs that can disrupt performance of their risk management tools and treat pooled producers inequitably during black swan events and times of major market imbalances — like have been experienced over the past five years under the average-of method. This is a benefit that is difficult to quantify, but is contained in this decision nonetheless.

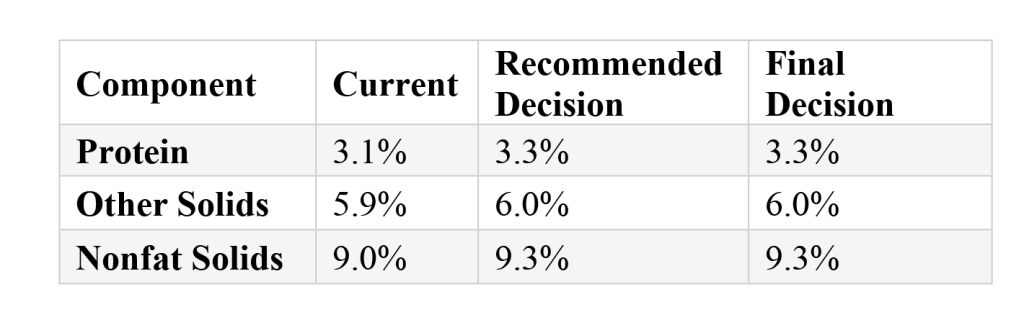

On the positive side for dairy farmers, the USDA will also shorten the delay from 12 months to six months for implementing the updated skim milk composition factors. These updates are shown above, which witnesses testified would raise Class I prices in all Federal Orders by an estimated 70 cents per hundredweight (based on 2022 data), while also increasing the manufacturing class prices in the four fat/skim Orders.

Raising the skim component standards helps bring the Class I, III, and IV in alignment, reduces the frequency of negative PPDs, and reduces the incentives for depooling that undermine orderly marketing.

The manufacturing class prices in the other seven Orders that use multiple component pricing are already paid on actual components, not by standardized levels.

Standardized butterfat composition at 3.5% will not be updated in this decision because this is a paper number that does not affect how producers are actually paid. Each pooled producer’s individual minimum price in all Federal Orders is already based on their actual butterfat test for pounds shipped.

The updates to county-by-county Class I location differentials were also tweaked in places, compared with the July preliminary decision, and the base differential for all counties at $1.60 per hundredweight remains in place.

Butterfat recovery within class and component formulas will be updated from 90% to 91%. Several proposals had requested a larger increase.

The Secretary’s final decision on the Class I base price mover remains unchanged from July.

USDA will restore the higher-of formula, which had been changed to an average-of formula in the 2018 farm bill. USDA is also sticking with the ESL adjuster, creating what is essentially a two-mover system for fluid milk.

Processors will separately report sales of conventionally processed (HTST) and ultra-pasteurized (ESL) fluid milk product sales each month. The higher-of method will set the base price mover, and USDA will apply the new ESL adjuster to the sales of ultra-pasteurized milk to determine their final pool obligation.

The ESL adjuster represents the difference between the higher-of vs. the average-of the Class III and IV advance pricing factors over a 24-month period with a 12-month lag. USDA states that it sees this adjuster “stabilizing” the difference between HTST and ESL over time.

USDA also rejected comments that had raised competitive concerns, stating: “The record does not contain evidence to support the implication that manufacturers of dairy products, the majority of which do not manufacture ESL products, would make business decisions to gain an advantage in the fluid market where they do compete.”

On the negative side for dairy farmers, the large increases in processor make allowance credits were made a bit larger, not reduced, after the 60-day public comment period.

USDA relied on the voluntary surveys of processor costs that were presented at the hearing as customary data sources from past make allowance adjustments. While USDA did not fully meet the requests of International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA) and Wisconsin Cheesemakers Association (WCMA), it does recommend much larger make allowances than what National Milk Producers Federation (NMPF) had proposed.

Make allowances represent the costs of converting raw milk into the four manufactured dairy products surveyed by USDA. They are embedded in the pricing formulas, not line items on a milk check, and they aggregate to an impact of 75 cents to $1.00 per hundredweight — depending on product mix and Class utilization.

USDA responded to processor comments about marketing costs, adding $0.0015/lb to its previously proposed processor make allowance credits for cheese, butter, nonfat dry milk, and dry whey. USDA also responded favorably to the processors’ request to adjust the nonfat dry milk make allowance to be more than a penny per pound higher than previously proposed.

The final decision will raise the make allowances on the four products used in class and component pricing – per pound — as follows:

Cheddar cheese will be increased from the current make allowance of $0.2003 to $0.2519 per pound; dry whey from $0.1991 to $0.2668; butter from $0.1715 to $0.2272, and nonfat dry milk from $0.1678 to $0.2393.

In its rationale, USDA stated that NMPF member-cooperative-processors supported the NMPF proposal as “a more balanced approach” to consider impacts on producers and processors. However, they also testified that the smaller increases proposed by NMPF “did not cover their costs.”

This put USDA in the position of having to rely only on the cost data provided by IDFA and WCMA because NMPF offered no cost data to support their smaller proposal. USDA said it rejected consideration of the impact on dairy farmers because the Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act does not include producer profitability as a factor for the Secretary’s consideration on this matter.

USDA chose not to wait for the mandatory and audited cost of processing survey that Congress is expected to authorize and require USDA to utilize in the future. This language is included in all versions of the new farm bill and is reportedly supported by NMPF, IDFA and American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF).

The final rule also removes 500-pound barrel cheese prices from the protein and Class III formulas, meaning only 40-pound block Cheddar price surveys will be used going forward. USDA rejected proposals that sought to add 640-pound block Cheddar, bulk mozzarella cheese, and unsalted butter to the pricing survey.

-30-