Duane and Marilyn Hershey (front right) can’t say enough about how their team of employees pulled together to free cows, restore order and keep 600 cows fed and milked in the hours after the roof collapsed Feb. 14 on about three-quarters of the main freestall barn at Ar-Joy Farms, Cochranville, Pa . They are pictured here with adaptable bovines eating TMR calmly under the open sky behind them three days later on Feb. 17

By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, Feb. 21 and 28, 2014

COCHRANVILLE, Pa., Feb. 17, 2014 – “The first thing we did was pray. Then we hugged. Then we got to work,” Duane Hershey recalls about the first moments in the wee hours Friday morning, Feb. 14 after he and his wife Marilyn were awakened by milking employees to learn the roof had collapsed on the freestall barn at their 600-cow Ar-Joy Farms, in Chester County, Pennsylvania.

His first thought was that it was a small section, but as he walked up the hill from the house to the barn – wife Marilyn a few steps behind him – a more devastating picture emerged in the dimly lit night sky, and all he could think was that he was facing a lot of dead cows.

All told, the Hersheys say they are thankful and fortunate no employees were in the barn at the time, and the majority of their cows got through the event fairly well.

“Nothing you train for prepares you for the reality of that moment,” said Marilyn Hershey, who has participated in crisis management workshops through DMI. “The truth is, when I came to the top of the hill and saw the rubble, I lost it,” she recalled during a Farmshine visit to Ar-Joy Farms Monday. “Duane reassured me that we would get through this, but that first moment of seeing the devastation and hearing our cows in trouble was horrific to me.”

One of Marilyn’s first calls was to Dean Weaver at Farmer Boy Ag. “We prayed for wisdom to know what the next step is, and we prayed for safety,” she said. “I called Dean at 3 a.m. and he answered. He got my brains started and pulled me out of the shell-shock. He told us to call our insurance company, and three hours later Farmer Boy Ag had their first crew here.”

One of Duane’s first calls was to friend and fellow dairyman Walt Moore at Walmoore Holsteins near West Gove, Chester County and to neighboring friends and farmers Andy Laffey and Tim Barlow.

“Everyone brought gates and chain saws,” said Duane. “We figured we had 50 to 100 cows trapped. We didn’t know what we were facing until we were able to move the tin.”

In order to free the trapped cows, they first had to move the free cows so they could start clearing debris to get to the cows that were still trapped in the original main barn. Moore organized the process of sorting and moving cows.

By 8 a.m., there were four construction crews on-site. Two crews were sent earlier by Dean Weaver at Farmer Boy Ag, the Hershey’s builder. Then Chris Stoltzfus got a call at White Horse Construction from a friend who explained the situation. He also sent two crews over to help. Burkhart Excavating, a local contractor, also came out to help.

“The generosity of people Friday just blew us away,” said Marilyn. “The four crews worked side by side all day, and people just started showing up. They knew what to bring. It was an overwhelming blessing to us.”

It took four to six hours of meticulous work to clear enough debris to free the nearly 100 trapped cows. “It was amazing how calm they were,” said Marilyn.

Walt Moore also observed this, recalling the cows “cacooned” under-tin, chewing their cuds as crews and volunteers methodically worked their way through the debris to free them.

The Hersheys give a lot of credit to herdsman Rigo Mondragon and the team of Ar-Joy employees for figuring out how to keep milking and tending cows, rotating them through the portion of the freestall barn that was still intact so that all the cows would get an opportunity to eat and drink.

“Walt is the one who really organized the work of freeing the cows,” the Hersheys related. “He knew what to do and could do it more objectively – without the emotional attachment we had to what was happening.” Walt’s wife Ellen called Dr. Kristula from New Bolton Center, and helped the vet check cows.

“This has been one of the toughest years I can remember, a winter that just won’t let up,” said Moore. “I was taken back more than once to see the community effort at Ar-Joy on Friday, to see how the farming community and their church family cares about each other.”

By Monday morning, agent Sue Beshore of Morrissey Insurance, the insurance carrier for Ar-Joy Farms, said she had heard from close to 10 customers with agricultural roof collapses, but that Ar-Joy was the first to involve so many livestock.

“This is a time for hugs,” she said to Marilyn before explaining the coverages the Hersheys had for the freestall barn their employees work in part of the time and their cows live in all of the time.

“We had 12 to 18 inches of snow the day before the roof collapsed, then some rain that iced over that evening before we got another 8 inches of snow that night,” Duane recalls, adding that there was already a snow pack on the roof from earlier precipitation and frigid temps.

Penn State ag engineer Dan McFarland notes that roof systems “are truly an engineered system. What the design of the roof allows for is the buildup of snow cover as measured by ground cover maps. In Southeast and South Central Pennsylvania, that might be 30 to 35 pounds. A light snow is 5 to 20 lbs per square foot. A snow pack is 30 to 40 pounds, a snow pack with ice can be 40 to 50 pounds, so now we are getting very close to what a lot of roofs are designed for.”

According to McFarland, a roof snow pack will absorb rain, and when that turns to ice, it doesn’t move and take longer to melt. In the short term, people like to get heavy loads off .

But McFarland urged extreme caution. “Be hesitant about going up without safety harnesses and tie-off ropes,” he said. “Metal roofs are slippery, so try to remove it, if you can, with a snow rake from the ground.”

Some ag building roofs are quite wide, which makes snow load removal more difficult. “If you are going to remove it, remove it evenly,” he advised. “One thing to avoid is uneven snow loads. Trusses are designed to carry the load to the load bearing points on the sides, so don’t prop them up in the middle because that can actually weaken the design.”

Good ventilation also helps. Condensation can deteriorate roof systems. Experts suggest evaluating truss systems for bowing and to contact professionals to evaluate or assist.

Drifting of roof snow pack, warming temperatures, additional rainfall getting absorbed, and blocked roof drainage systems all contribute to uneven or excessive snow loads. Strained roofs surviving the weight from this week’s rain bear watching in additional storms later this season. Cold air is expected to return next week, bringing additional snow in some areas.

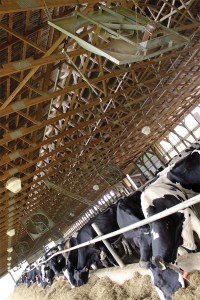

One week after the roof collapsed, rebuilding is underway at Ar-Joy Farms Thursday, Feb. 20. Farmer Boy Ag carpenters put up wood bracing after 69 trusses were set for the steel roof construction.

Loss gives way to profound gratitude

COCHRANVILLE, Pa. — Feb. 20, 2014 — The cattle losses at Ar-Joy Farms here in Chester County, Pennsylvania have grown to two dozen in the wake of the February 14 roof collapse over the main 275-feet of freestall barn, which left only the newer 92-foot section of roof standing. But Duane and Marilyn Hershey have not had to handle any of this alone.

By the following Saturday (Feb. 22), 69 new trusses were set and the 600 cows had a new roof — thanks to the efficiency of friends, neighbors, insurance adjusters, structural engineers, and the crews at Farmer Boy Ag.

The farming and church communities reached out to the Hersheys immediately that Valentine’s Day morning, and also had a work day one week later to prepare the site for crews to set new the trusses and raise the new roof in the three-day window of warm weather before the frigid cold and precipitation returned to Southeast Pennsylvania this week.

Friend and business partner in Moocho Milk hauling, Walt Moore of nearby Walmoore Holsteins, West Grove, was the first to arrive on the scene in the wee hours of that Friday morning.

“They were overwhelmed,” said Walt of his friends. He felt like it took him and his wife Ellen forever to load the service truck with whatever they could think of needing and to traverse the snow-covered and icy roads to Ar-Joy Farms.

Walt and Ellen Moore got the 2 a.m. phone call Friday morning, Feb. 14 from Duane and Marilyn Hershey that 275 feet of their main freestall barn roof had collapsed upon the 320 stalls and cows below.

“The biggest thing we could do was to bring what we thought would be needed and to help organize the next steps. We have similar operations,” Walt explained. Ar-Joy milks 600 cows while Walmoore milks 850. “When we got there, it was emotional to see, but I was able to be less emotionally-attached in that moment about what to do next.”

For example, Walt immediately saw that the lights were on so he wanted to first secure the electrical situation before proceeding with freeing cows and cleaning up debris.

Marilyn says that a farmer’s impulse in a time like this is to call another farmer. Who else would understand the situation, to know what was needed, and be able to bring clarity of thought?

“Walt was a big help to me,” Duane added. “I was able to bounce ideas off him, and he could be objective and see things I couldn’t see in that moment.

“You are kind of in shock and you lose the concept of time. It’s hard to explain the magnitude of it,” Duane recalled those first moments when the roof collapsed sometime around 1:30 a.m. His first impulse to run in and try freeing some cows was barely forming in his mind when another surge of collapsing roof brought the whole thing down.

What followed was an overwhelming silence, except for the occasional sound of metal scraping metal and cows lowing in distress. The milkers had stopped milking, and they all stood frozen with Duane and Marilyn for a few moments, mulling their options in the pre-dawn darkness.

When Walt Moore, Andy Laffey and Tim Barlow arrived with gates for sorting cows, the race was on. As reported last week, four construction crews from two companies, along with scores of neighbors helped the Hersheys and their team of employees sort, milk and feed cows; clean up wreckage; and restore a semblance of order to the farm.

They had one group of cows that had found their own way through the fallen roof wreckage and were corralled in the middle of the barn with no path out. “We cut a tunnel through the fallen roof for those 200-plus cows to walk through,” Duane recalled. “Everyone kept saying they can’t believe how calm the cows are, but that’s because we had so many farmers come help us. They knew how to handle dairy cows.”

Four to six hours later, cows were freed, some were put down, others were tended by Dr. Kristula of New Bolton, a group of 100 were transported to Walmoore for temporary housing, and the milking had resumed. “We had enough barn cleaned up for the cows to eat and drink,” Duane said. “They couldn’t all lay down, but at least they could eat and drink.”

Employees cycled them through feeding areas in the upper part of the barn that was still standing and the lower bank barn where the Hersheys normally keep transition cows.

Two of the Hersheys four children who live somewhat locally and got to the farm as fast as they could — given the condition of the roads in the early morning hours following the barn roof collapse on Feb. 14. “The first thing we did was give hugs,” said daughter Kacie, who lives in Lancaster County and had been text-messaging her mother Marilyn some reassuring Bible verses. Their son Kelby lives in Maryland. He just returned from his Army tour of duty in Afghanistan two weeks ago. He said it would have been much more difficult to hear of this and be a continent away. He was glad he could be home to help. Stephen lives in New York and Robert attends college in Montana.

Daughter Kacie and son Kelby were able to get to the farm that morning. Kacie had been text-messaging her mother comforting Bible verses. Kelby was ready to dig in and help. He lives in Maryland and had just returned from his Army tour of duty in Afghanistan two weeks earlier. Son Stephen lives in New York and Robert attends college in Montana.

“The first thing we did was hug our parents,” said Kacie, whose text messages had provided the inspiration Marilyn needed to kick down the wall she had hit emotionally.

The Hersheys can’t say enough about their team of employees and how they worked together to keep the cows milked and fed during the ordeal. “It’s unbelievable how back-to-normal they seem,” said Marilyn. “Yes, our production is off, but the cow behaviors are back to normal.”

As for the rebuilding, the Hersheys are thankful how that came together. “Sue Beshore (Morrissey Insurance) always told us to keep that replacement value in our policy even though we were tempted sometimes to drop it,” Marilyn recalls. “We are so glad to have that.”

The Hersheys were also glad the adjuster gave them the freedom and flexibility to immediately tend their cattle and clean up so the roof replacement could be done immediately before the next round of frigid cold and snow in the forecast.

Cows were amazingly calm at Ar-Joy Farms as their new roof went up one week after the old one collapsed under the weight of extraordinary snow and ice pack. Owner Duane Hershey (red shirt) stepped out of his comfort zone to help the building crews who were pushed to get as much done as possible Thursday before the rain and wind on Friday.

The bottom line in this story is how important it is for people to “hold each other up when facing a disaster,” said Duane. “To have friends and neighbors like that, just to see them there, it’s something I can’t explain. A lot of them left their own farms on a snowy morning to come here and help us. What can I say that really expresses our gratitude?”

The couple also received calls from dairy farmers in New York who had been through roof collapses. They gave advice and suggestions.

“You learn how important friendships are,” added Marilyn. “This is a tight farming community. I can’t tell you how thankful we are.”

Click here for more photos

By Sherry Bunting, columnist, Register-Star, Feb. 21, 2015

By Sherry Bunting, columnist, Register-Star, Feb. 21, 2015 They have a different temperament about the whole calving deal.They aren’t worried about predators and trust the humans they work beside day in and day out to care for them and their offspring.

They have a different temperament about the whole calving deal.They aren’t worried about predators and trust the humans they work beside day in and day out to care for them and their offspring.