By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, Sept. 6, 2024

EAST EARL, Pa. – “Those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” That was the theme of the American Dairy Coalition’s webinar on the USDA’s proposed Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) pricing changes, which I participated in last Thursday, August 29th.

Over 125 people participated, including state dairy and state farm bureau organization leaders and individual producers. American Farm Bureau economist Danny Munch helped producers understand the proposed changes and walked through the areas of mutual concern. Other panelists offered information, and participants’ questions were addressed.

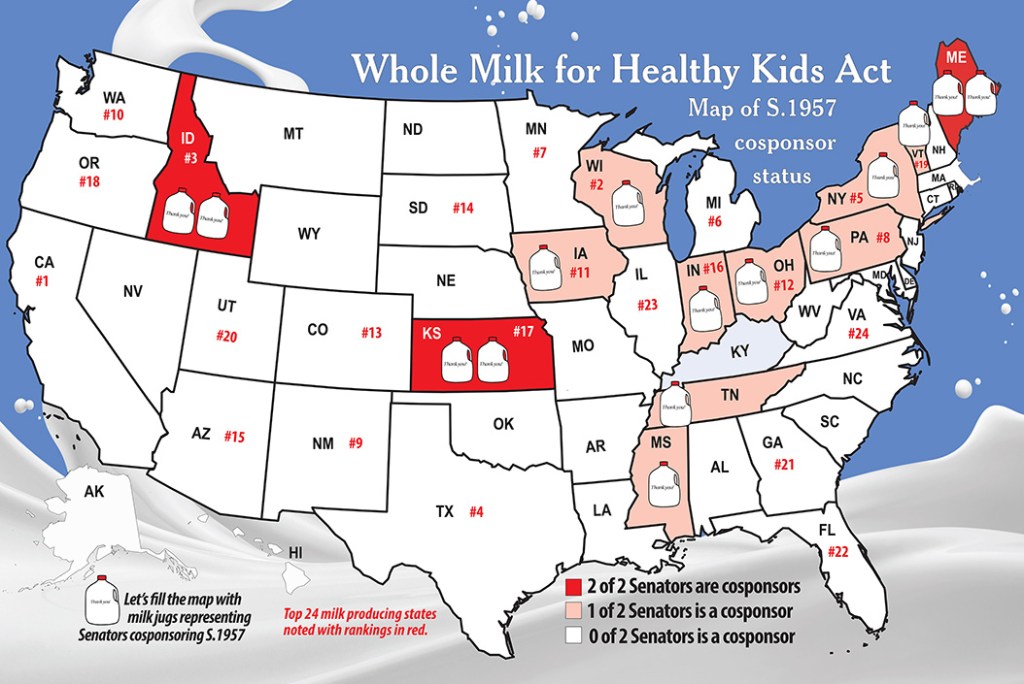

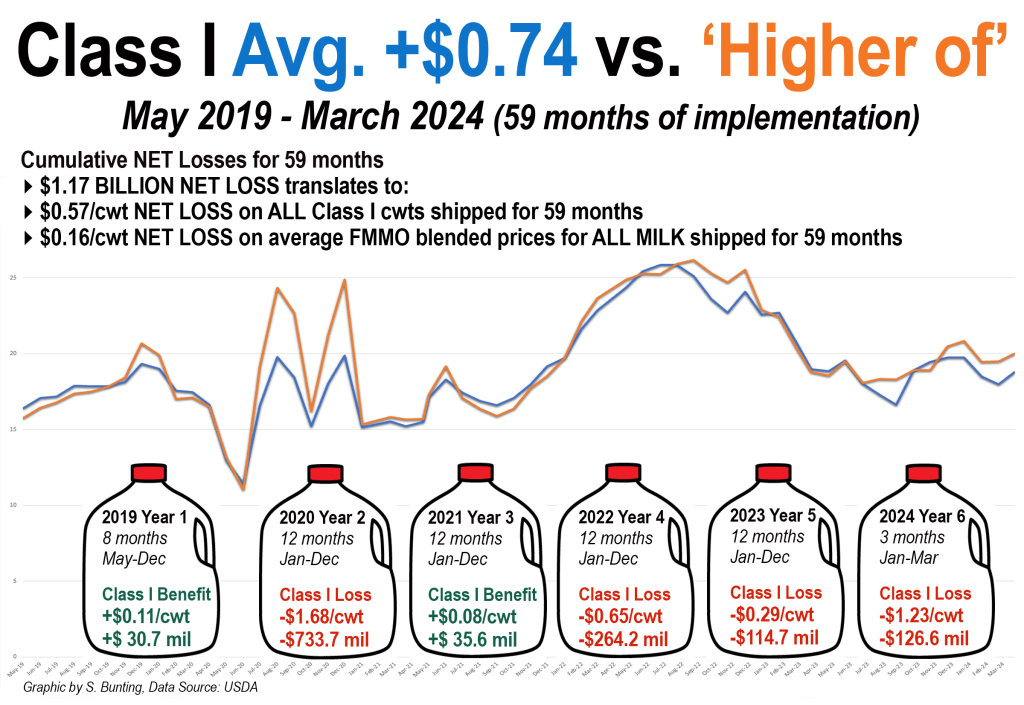

“This webinar was a grassroots dairy producer undertaking,” said moderator Kim Bremmer of Wisconsin-based Ag Inspirations. “ADC planned it to make sure dairy farmers have a way to ask questions before the public comment period closes on Sept. 13th. We know the last update to milk pricing occurred in that 2018 farm bill, and that was without your input, and it cost dairy producers over a billion dollars across the country. It is really important that your voices are heard.”

Four primary areas of concern were discussed: the processor make allowance increase, the size of the whey make allowance relative to the price, delayed timing of beneficial updates to milk composition, and the surprising 2-mover system for Class I, effectively adding a 5th class of milk to the FMMO pricing scheme.

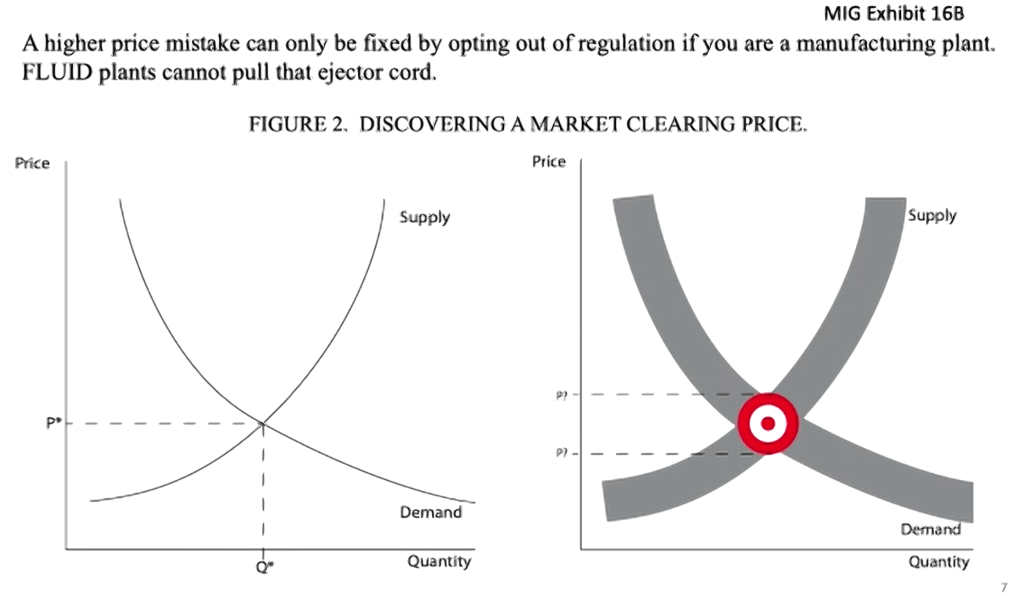

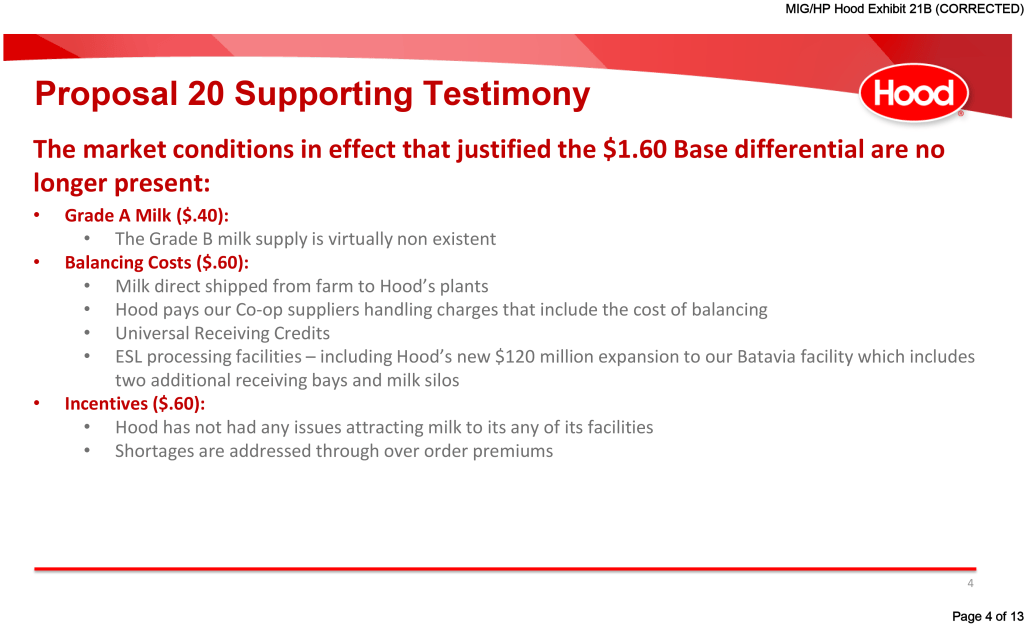

A 2-mover system was not vetted during the very lengthy USDA hearing. It appears to be “thrown in” as a last-minute compromise to appease processors investing in extended shelf life (ESL) fluid milk capacity.

Nestle and Fairlife had testified to sales volume growth when they offered 9 to 12-month flat-pricing after the average-of was implemented in May 2019. They said they must have average-of pricing to manage their risk so they can offer long-term pricing to grow sales.

Make allowance increases quite large

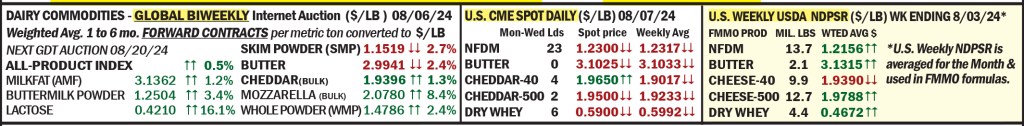

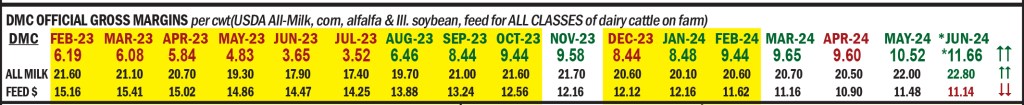

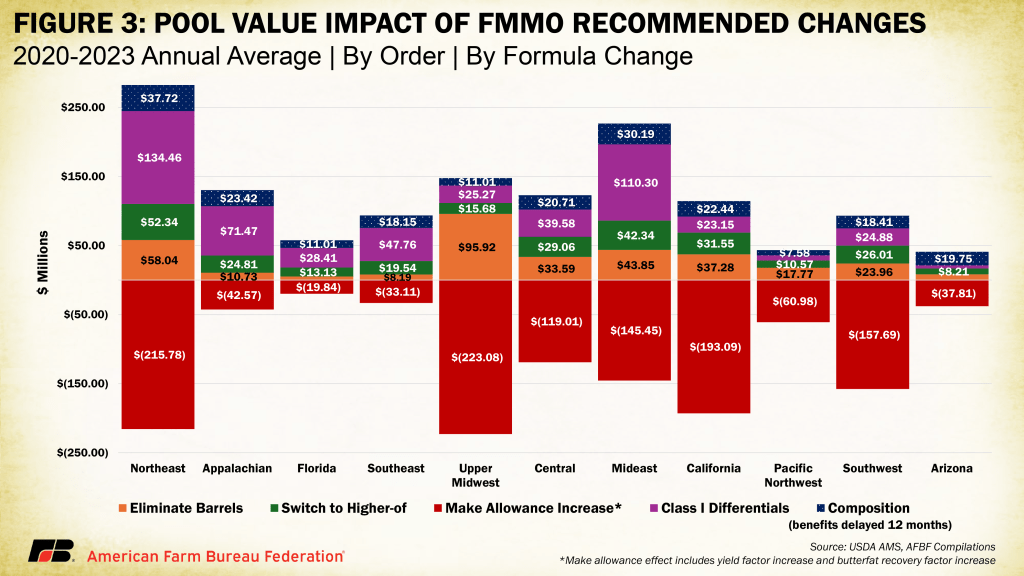

USDA proposes to raise processor make allowance credits by 29 to 33% above the current level. That equates to a 75-cents to $1.00 per hundredweight new deduction from milk checks, embedded in the pricing formulas, depending on how the milk was utilized.

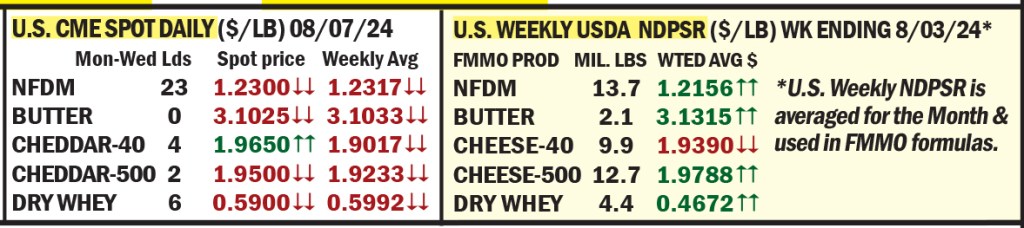

Munch said make allowances are part of the formulas that start with surveying market prices for the four base commodities – 40-lb cheddar cheese blocks, butter, nonfat dry milk, and dry whey. USDA works backwards from the surveyed price to derive a value for the raw milk.

He used a cartoon imagining of “little Zippy selling cheese at his cheese stand.” (a light-hearted reference to AFBF president Zippy Duvall, a former dairyman).

“USDA is surveying the volume and value that he is selling it at — out in the marketplace — and then is using that price to derive a raw milk price,” Munch said, explaining that, “working backward, there has to be a part of the formula that accounts for the cost for Little Zippy to convert the raw milk into the cheese. He uses non-dairy ingredients like cultures and salts. It’s his own labor as well as overhead and equipment that he uses to convert raw milk into cheese. In the FMMO system, that deduction that accounts for his costs is called the make allowance,” he continued.

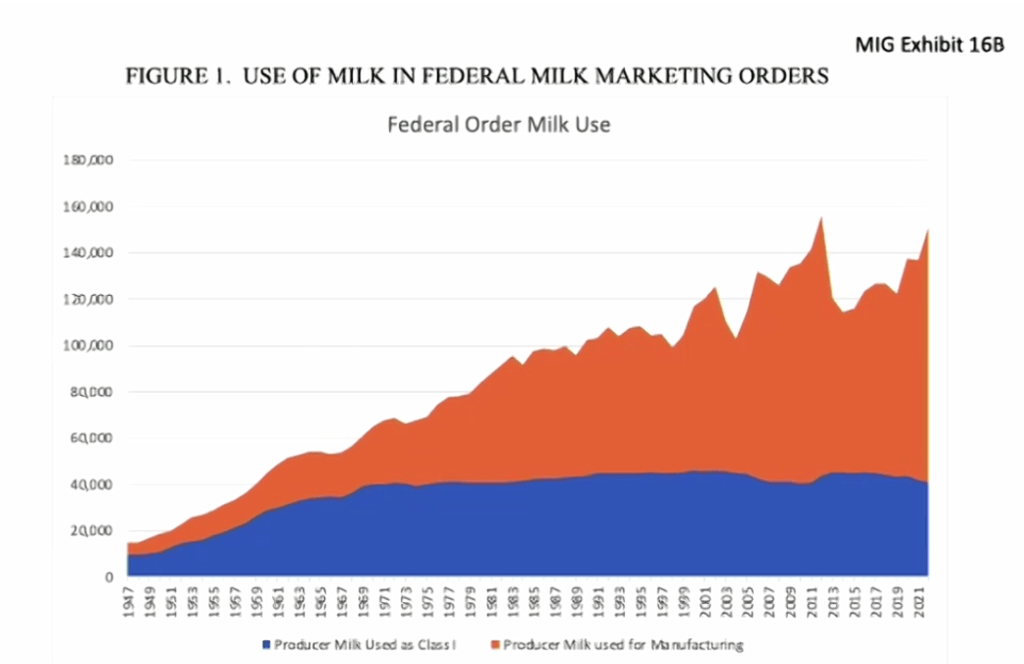

But today, the Little Zippys of the dairy industry are not so little, and they report much less on the USDA price survey, and they make so much more of the products that are NOT price-surveyed. These other products — such as mozzarella cheese, pizza cheese, other non-cheddar cheeses or cheddar cheeses in other bulk package sizes, whey protein concentrate, skim milk powder, whole milk powder, unsalted butter, and on and on — are not part of the formula and do not contribute value to the farmer’s milk check. Class I and II products are not price-surveyed either.

“When we look at the surveys, so many things are made out of the wonderful perfect nutrition of milk made on our farms, so what is the percent of products that are actually represented in the surveys?” asked Indiana dairy producer Sam Schwoeppe, who moderated the webinar Q&A

Survey volume quite small

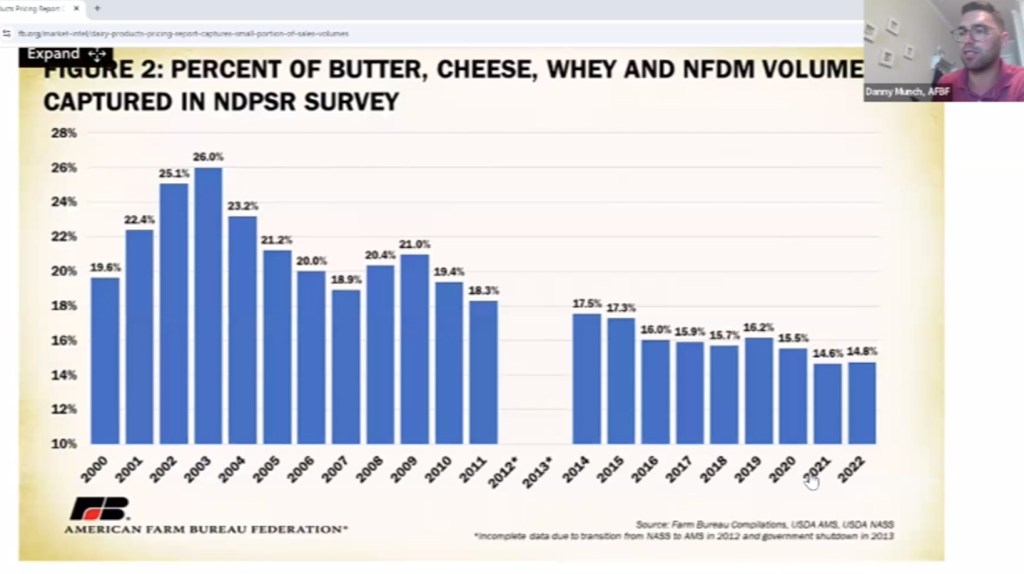

Munch said the volume captured is “quite small and declining” to 14.8% in 2022 after being a high of 26.4% in 2002. “But those are just the products that are actually surveyed. There’s a lot of products that are not even surveyed, and that means the percent is even less.”

American Farm Bureau, American Dairy Coalition, and others pushed for some other bulk products to be added, but those proposals were rejected in this USDA decision.

So, how can current make allowance levels be too low when processors are spending billions to expand? Or, are dairy farmers expected to pay this debt service?

Dr. Michael Dykes, the CEO of the International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA), representing processors, told dairy farmers at the Georgia Dairy Conference in January 2024 that, “7 billion in new processing investments (below) will be coming online in the next two to three years. There’s a lot of cheese in those plans. These are going to be efficient plants. You’re going to see consolidation.”

The proposed make allowance increases of 5 to nearly 7 cents per pound across the four commodities equate to a new embedded milk check deduction of nearly $1.00 per hundredweight for Class III and around 75 cents for Class IV – over and above the current make allowances that already equate to $2.20 to $3.40 per hundredweight. Class I would see this embedded in advance skim and fat pricing factors that are used to set the base price mover.

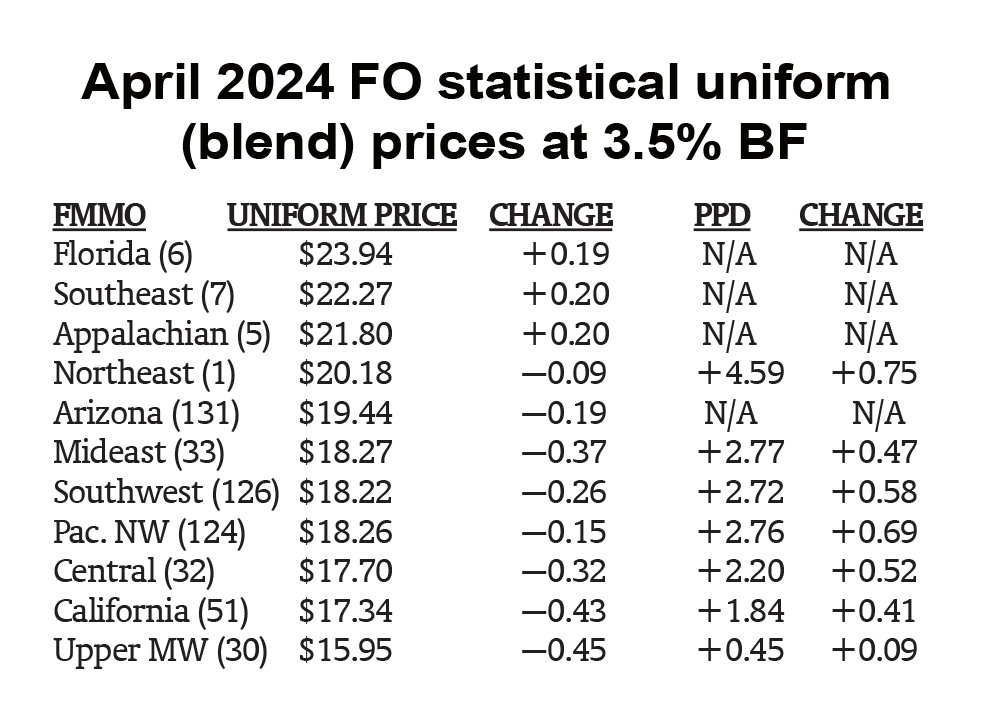

Collectively, the make allowance increases could remove $1.25 billion annually from FMMO pools, Munch showed in a 5-year static analysis based on prior pool composition, (See chart at top). Other aspects of USDA’s full proposal will defray some or all of the loss, mainly in the FMMOs with more Class I utilization. USDA’s proposal includes increases in location differentials for Class I fluid milk.

What happened in 2008-09?

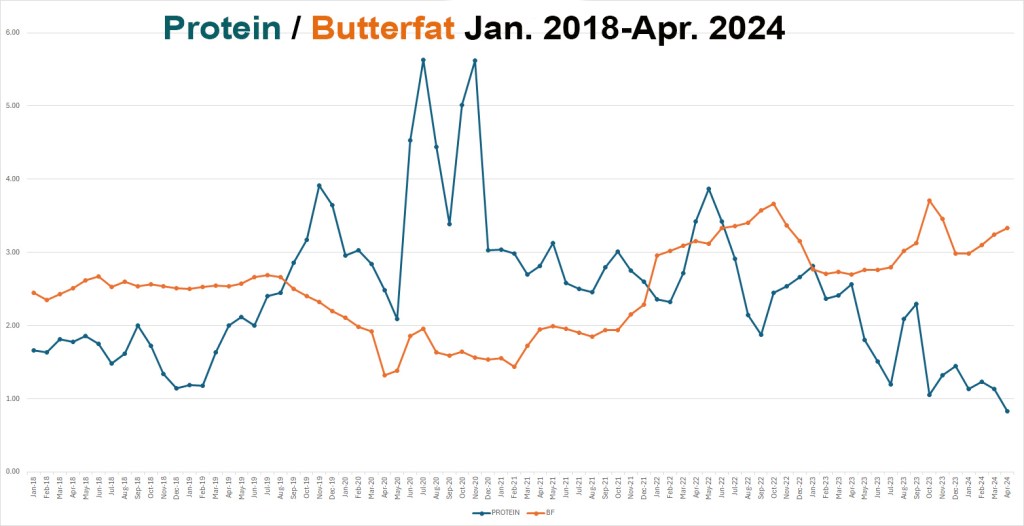

Learn from the past or be doomed to repeat it? The last time make allowances were increased in 2008, a dairy market crash followed. As a webinar panelist and ag journalist, I pointed out that the dry whey price fell below the dry whey make allowance for the first seven months of that implementation from October 2008 through April 2009, resulting in penalties deducted from milk checks on every pound of other solids in the milk.

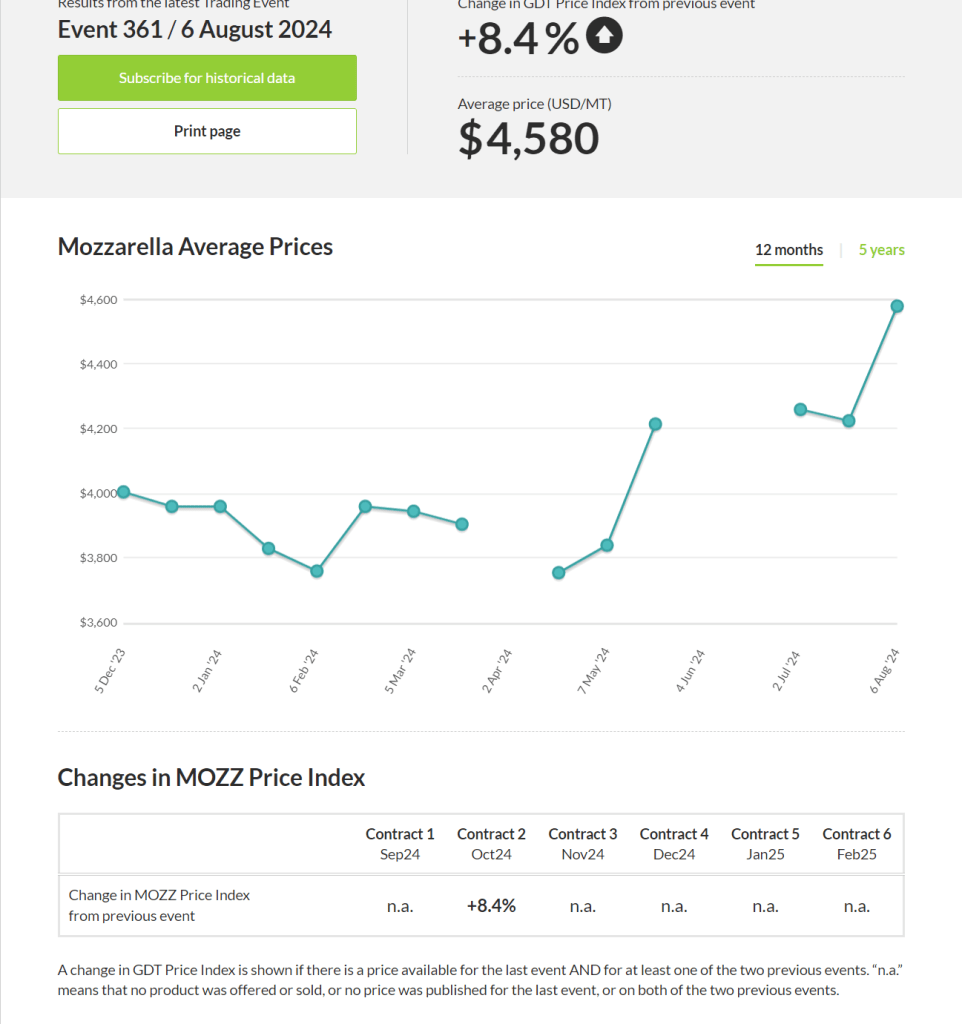

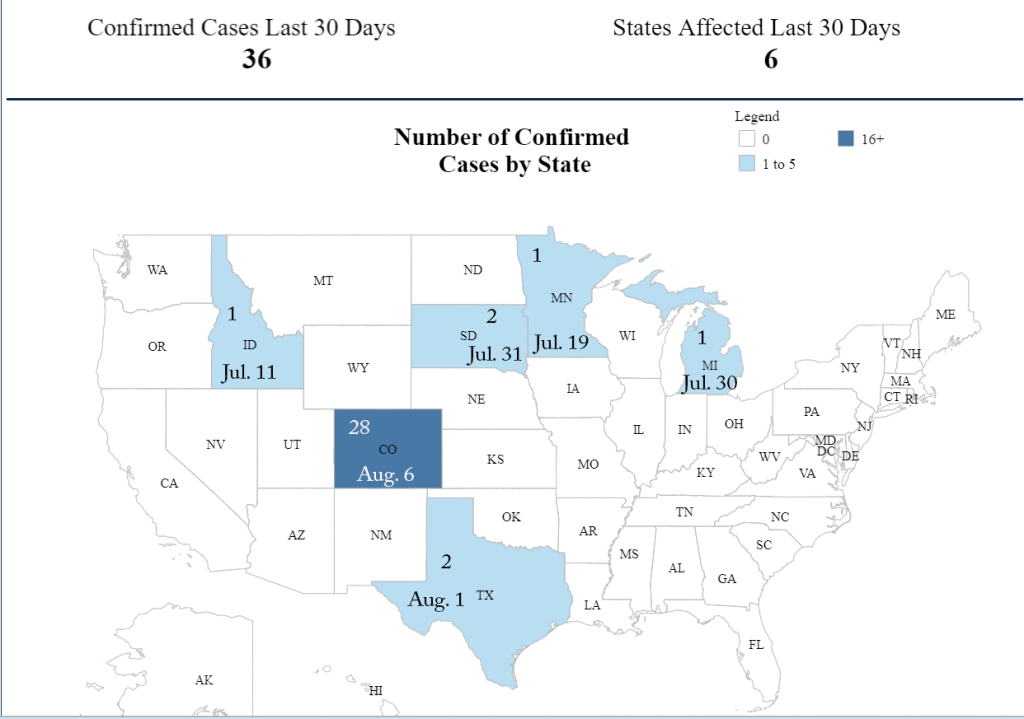

This time, the proposed dry whey make allowance is the largest of all – up 33.2% from $0.1991/lb now to $0.2653/lb. If in effect a year ago, dairy farmers would have again seen negative other solids penalties on their milk checks in July and August 2023 when milk prices were at their lowest. Meanwhile, processors made less dry whey, instead making more value-added products that are not price-surveyed.

Munch noted that only 66% of the plants on the price survey actually participated in the voluntary cost survey used by USDA to set the proposed new make allowances. AFBF, ADC and other organizations have been on record opposing make allowance increases until mandatory, audited surveys are conducted by USDA.

Conversion from fresh milk to ESL?

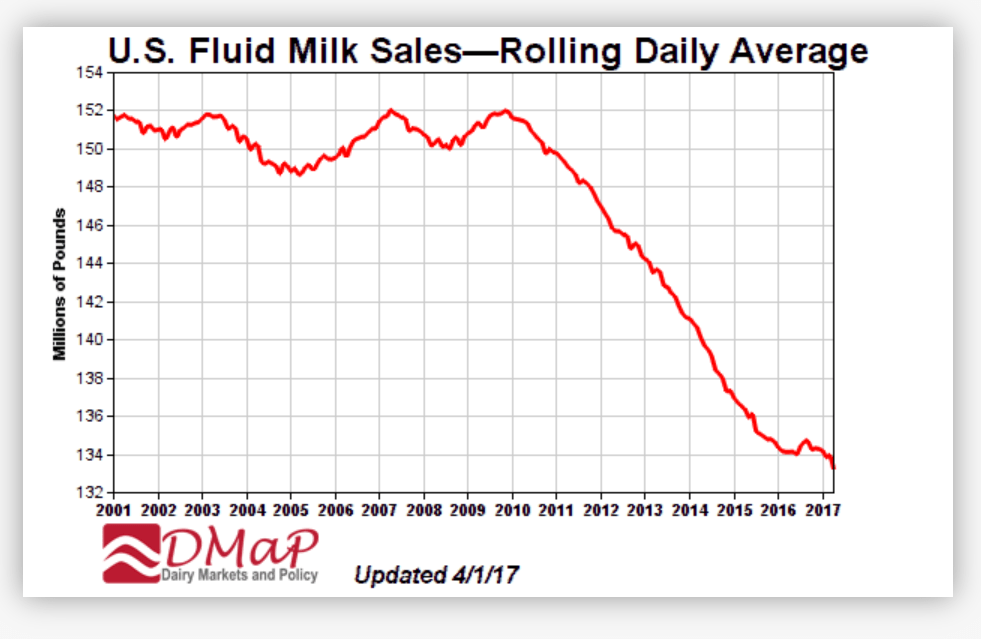

Learn from the past or be doomed to repeat it? On the Class I side, the 2018 farm bill changed the base price calculation. Farmers were told this would be revenue neutral, but the change cost them – at minimum — $1.25 billion over the past five years.

USDA now proposes to restore the higher-of calculation, but only for conventionally pasteurized HTST (or fresh) milk. Extended shelf life (or ESL) fluid milk products — labeled good for 60 days or more — would be priced using a new average-of method with a rolling adjuster.

Shouldn’t ESL have been defined in the hearing, and the economic impacts studied? This idea of two different Class I movers was not vetted in the hearing.

With two movers, fluid milk costs could be different from the same location based on shelf life. Webinar comments questioned USDA’s loose definition of ESL; Could processors change the label to move between the movers and pay whichever mover was lower?

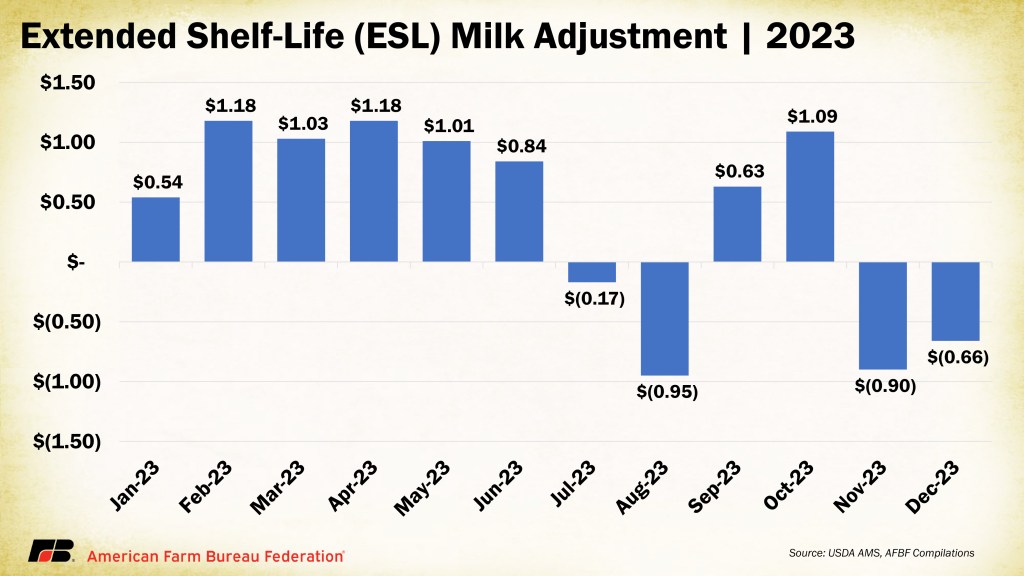

The USDA’s one-year static analysis showed the ESL Class I mover would have ranged from being $1.18 per hundredweight over to 95 cents under the HTST Class I mover in various months of 2023. That’s a big spread.

What’s at the root here? The dairy checkoff has openly identified ESL milk as the new milk beverage platform, using dairy farmer funds to research and promote it and to show consumers can be ‘taught’ to accept it.

Dr. Dykes of IDFA, at the Georgia meeting in January 2024, also told dairy producers that “this is the direction we (processors) are moving… to get to some economies of scale and bring margin back to the business.” He said the planned new fluid milk processing capacity investments are largely ultra-filtered, aseptic, and ESL. (10 of the 11 fluid milk plants on the IDFA map above are ESL and/or aseptic fluid milk plants. Some will also make ultrafiltered milk, and some will make plant-based beverages at the same location.)

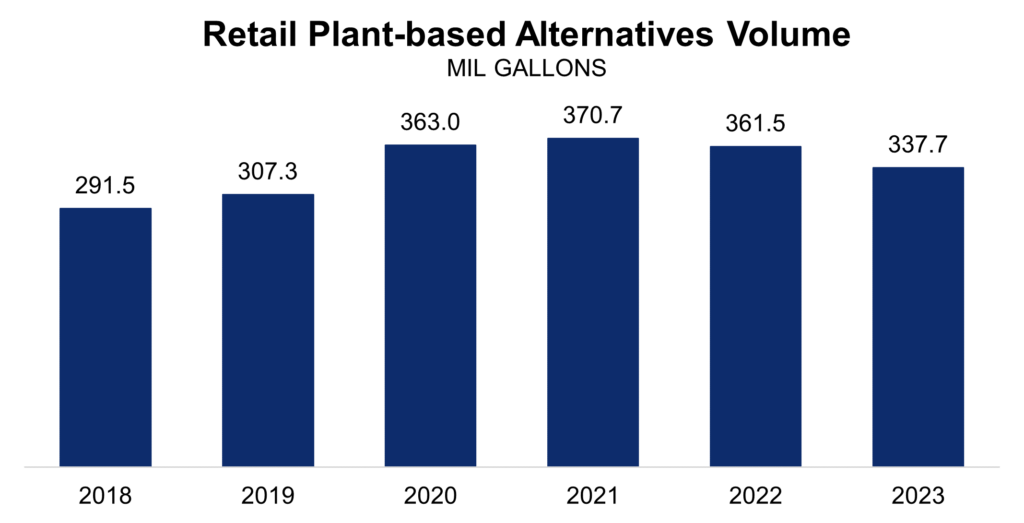

Has USDA considered the purpose of the FMMO system is to promote orderly marketing and the adequate supply of FRESH FLUID MILK? Will consumers accept the taste of the not-so-fresh ESL and aseptic milk, or migrate faster to other beverages if fresh fluid milk is less available to them?

Would a 2-mover system ultimately reduce farmers’ access to milk markets in some regions and diminish the food security of those consumers? Prized as the freshest, least processed, most regionally local food at the supermarket, will the USDA decision reduce fresh fluid milk availability down the road?

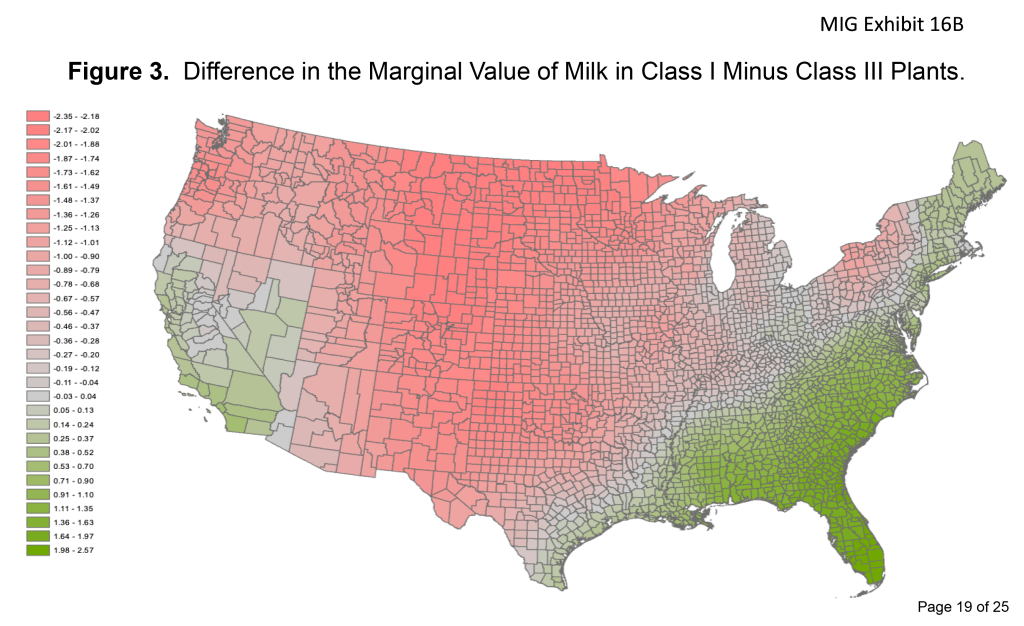

How will the 2-mover system impact dairy farms located outside of the industry’s very specific identified growth centers? And will this perpetuate the wide divergence between Classes III and IV that has been an issue since 2019, further punishing dairy farmers with disorderly marketing and opportunistic depooling?

Webinar participants asked: “Will commenting even matter? Or is the USDA Secretary’s mind made up? How important is individual farmer input?”

“It’s extremely important for farmers to get involved. Even with talking points, really tell your own story with it,” said Munch. “They like hearing from you, and the stories of the impacts to your balance sheet, to your future revenue or the stability of your local community. They want to know the impact on small businesses. That’s one of the driving points.”

Not much time

With a short time remaining to comment at the Federal Register Docket AMS-DA-23-0031-0002.

American Dairy Coalition has prepared an official comment, so other like-minded organizations and individuals can sign on before the filing deadline, which is 11:59 p.m. Friday evening, Sept. 13, 2024.

Comment directly to the Federal Register docket at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/07/15/2024-14769/milk-in-the-northeast-and-other-marketing-areas-proposed-amendments-to-marketing-agreements-and

Click here to read the ADC’s comment that will be filed before the deadline Friday evening at Sept. 13 at 11:59 p.m. Dairy farmers and organizations wanting to associate themselves with the comment can click here.

Click here to view ADC’s Aug. 29 webinar.

Click here to read Danny Munch’s at Farm Bureau Market Intel.