(Excerpts from Sherry Bunting’s Milk Market Moos column in the Apr. 25 and May 2 Farmshine. Get the full Farmshine delivered weekly at a low subscription rate at farmshine.net)

The current dairy trade is ignoring the calendar composition on key reports — adding to bearish sentiment that has forced key dairy commodity prices lower and pushed mailbox milk prices below year ago, despite earlier 2025 forecasts had suggested a raise this year for dairy farmers.

Cheese inventory was down 4% year-on-year (YoY) at the end of March, according to USDA’s April 24 Cold Storage Report. The percentage of the YoY deficits did shrink from January to February and February to March, so some in the trade believe this means stocks are building, and that this trend will worsen as plants ramp up newly commissioned capacity as the year progresses.

But the trade is ignoring the calendar composition. Daily production of cheese actually increased (leap-year-adjusted) during the first quarter of 2025, making this small erosion in the March margin of YoY deficit less worrisome in its reality.

Let’s look at the February Dairy Products Report released on April 3. It stated to the trade that cheese production was lower YoY. But this statistic did not adjust for the extra leap day on the February 2024 calendar. When we adjust the February figures to reflect the extra day of processing last year, we see a much different picture.

The leap-year-adjusted total cheese production for February was UP (not down) 1.3% YoY. American-type cheese production in February was UP 2.2% YoY. And the leap-year-adjusted production of fresh Italian cheeses (made to order) was UP 3% YoY. Despite heavier cheese production, we still had an inventory deficit in February and again in March. We won’t see March cheese production totals until the USDA releases them on May 6.

Bottomline, the leap-year-adjusted numbers show: U.S. manufacturers — in reality — are making more cheese YoY and storing less cheese YoY.

Let’s look at butter. Stocks were up 4% YoY at the end of March. This compares to a 17% overage reported at the end of February, which had one less day to eat it and sell it vs. year ago. Still, the March stockpile was the second largest March inventory in three decades.

But again, let’s review the calendar! The 2025 Easter and Passover holidays were much later than normal this year — occurring past the mid-point of April. How much holiday butter was moved after the March inventory report? We’d wager on this! USDA Dairy Market News mentioned heavy retail featuring of butter and cheese in its weekly reports for weeks ending April 4, 11 and 18. We will reserve judgement on butter sales and inventory until the March production totals are reported on May 6 and end of April inventory figures are released on May 23.

The butter trade, meanwhile, has reacted bearishly to the YoY comparisons without considering calendar composition factors. Today’s wholesale butter pricing on the CME spot market shows U.S. butter can be bought by domestic and international buyers at a substantial 40 to 45% discount compared with the uptrending Global Dairy Trade indexes. Was that severe discount necessary to move it? Or was it speculative and opportunistic?

Meanwhile, farmers will pay the piper (Fig. 1) while processors bemoan the slow response of dairy farmers to what they describe as “a market signal for milk production growth.”

Really? Maybe try checking the batteries on those lights believed to be lit in the Bat Signal. By no means are producers flooding the market with milk, and yet here we are with the 2025 milk price forecast lowered nearly $2 from the January WASDE to the April WASDE.

Meanwhile, processors wonder why dairy farmers are making so many beef crosses instead of dairy heifers, which is keeping a lid on milk growth by large throughput dairies to fill new processing expansions. Dairy farmers began managing their heifer inventories with beef crosses in 2015. Ten years later, American Farm Bureau economists estimate 72% of dairies are doing it as beef semen sales to dairies have jumped from indicating over 111,000 beef-on-dairy calves in 2015 to 3.2 million in 2024.

The real all-cost profit margin on that beef-on-dairy wet calf is larger than the margin on the milk from its dam all year. It’s math.

U.S. dairy trade paradigm shift underway

Several market factors are converging simultaneously: 1) The new tariff uncertainty; 2) The dairy trade’s preparation for new FMMO formula rules on June 1st; 3) Historic foreign investment in U.S. dairy processing growth with sights set on growing international sales as low-cost-producer; and 4) U.S. dairy product prices are at steep discounts below the Global Dairy Trade (GDT).

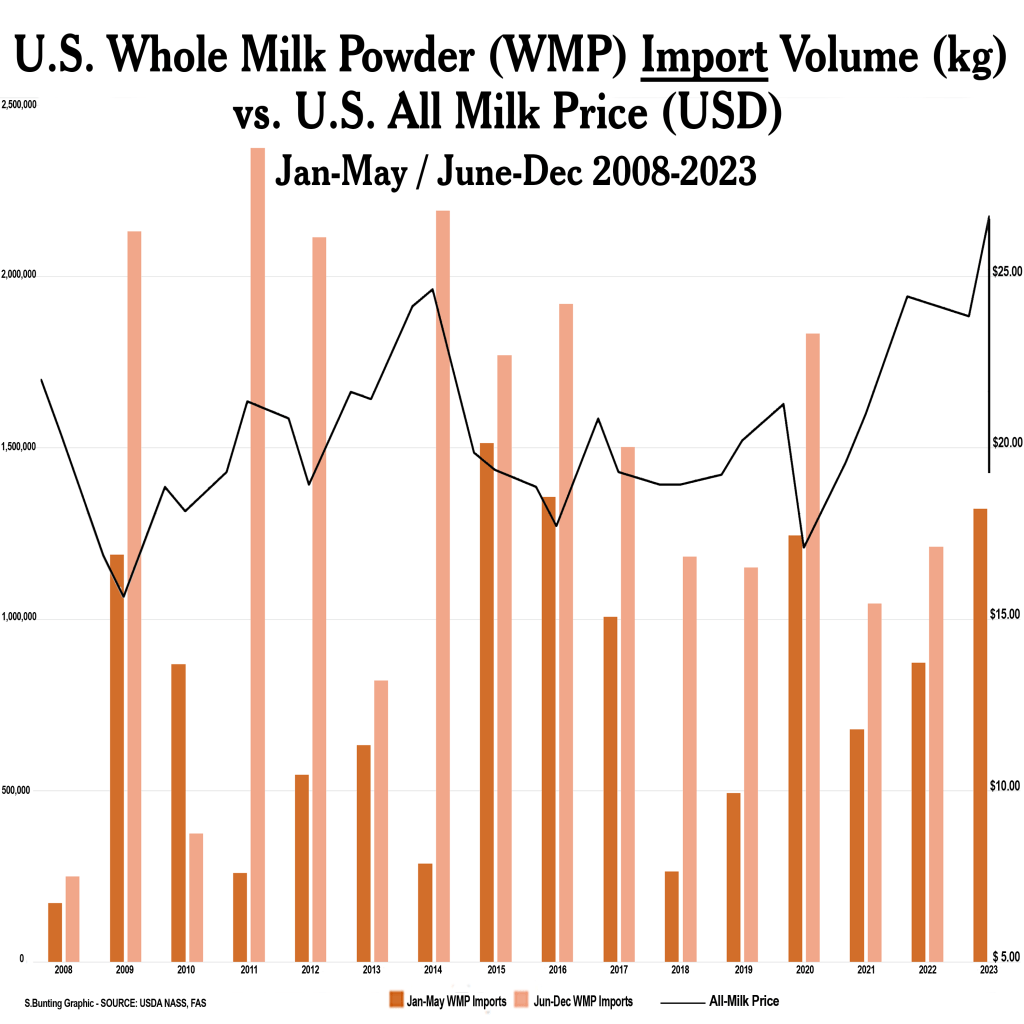

U.S. dairy has gone from running trade deficits on a value and volume basis before 2007 to running significant trade surpluses, especially from 2014 to 2022. In 2023-24, dairy exports flattened alongside growth in dairy imports from 2021 to 2024. On a volume basis, U.S. dairy exports represented 16% of U.S. milk production on a milk solids equivalent (MSE) basis for 2023 and 2024. This is four times the volume of imports, which grew to 4.2% MSE in 2024. Tariffs, a weaker U.S. dollar, and discounted U.S. product prices should lower U.S. dairy imports in 2025.

On the export side, the dairy trade paradigm has shifted to exporting higher-value products like cheese, and doing so as low-cost producer. 2024 saw record volumes of exported cheese (+17%) and butter (+7%). This continued into 2025 with Jan-Feb cheese export volume up 7% YoY, butter up a whopping 236%.

In its Apr. 18 weekly report, USDA Dairy Market News stated: “Demand for butter from international buyers is strong.” No surprise, considering U.S. butter at $2.32/lb is discounted 45% at $1.16/lb below the global butter price index of $3.48/lb (Fig. 3). U.S. cheese is attracting international interest at a nearly 30% discount as U.S. 40-lb block cheddar ($1.76/lb) undersells the global index ($2.32/lb) by 55 cents per pound (Fig. 2).

Meanwhile, the GDT index on whole milk powder (WMP) was higher for the past few sessions and the global pulse market in between pegged WMP at its highest price level in three years.

These global market trends would normally boost U.S. dairy markets. Not so today. The undercurrent of drilling down the price to be low-cost-producer of high-value overseas sales categories began last summer and has been exacerbated in Q1 2025 by the threat of retaliatory tariffs. At these discounts, plenty of U.S. product can move offshore, tariff or no tariff. If the market suppression has been in vain, meaning no retaliatory tariffs from trading partners for cheese, and in relation to domestic retail prices that may or may not come down — someone stands to make a lot of money, and it won’t be the farmers.

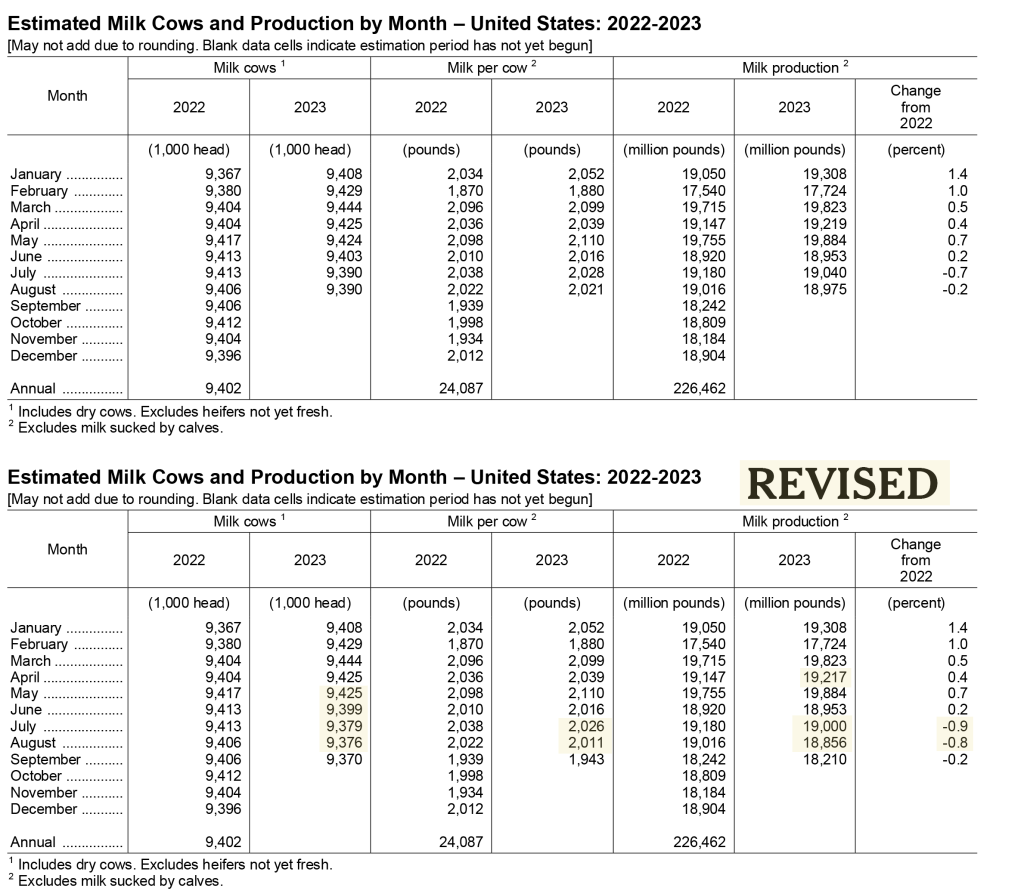

March & Feb. milk production up 0.9%

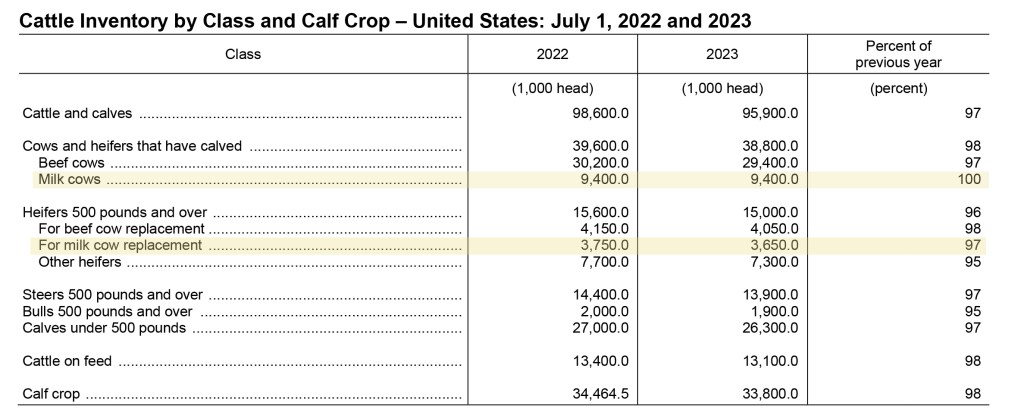

USDA’s March Milk Production Report on Apr. 22 tallied 19.8 bil. lbs, up 0.9% year-on-year (YoY). Feb. was revised higher, up 0.9% also (leap-year-adjusted). Milk output per cow grew by 0.3% YoY in March, and U.S. dairy farms milked 57,000 more cows YoY.

No. 3 Texas added 45,000 head, with milk up 9.4% YoY. For the first time in 4 years of major losses in production and cow numbers, neighboring New Mexico reported 2000 more cows making 1.5% more milk. South Dakota added 9000 cows and 5.1% more milk. No. 4 Idaho milked 29,000 more cows making 4.3% more milk. Kansas added 8000 cows with 4.4% more milk. No. 1 California continued lagging, down 2.1% as bird flu continues, though it is diminishing. No. 2 Wisconsin was up 0.1%, with 5,000 fewer cows. In the Mideast, 2000 more cows were milked, collectively, with Michigan’s milk up 1.3%, while Indiana and Ohio both gained 0.8%.

In the East, No. 4 New York increased production 1.3% with no added cows. No. 8 Pennsylvania as well as Virginia had milk production equal to a year ago, and both milked 1000 fewer cows. Vermont’s output grew 0.5% with 2000 fewer cows. Georgia grew by 4.1%, without adding cows. Florida declined 3.6% with 5000 fewer cows.

Even with two consistent back-to-back gains just shy of 1% in U.S. milk production, growth is still around half the annualized average growth curve that the U.S. dairy industry was on pre-Covid. Milk production growth, post-Covid — whether by cow numbers, output per cow or even the big jump in component levels — still lags the overall pre-Covid growth curve of 1.8% per year.

This was explored recently in a Milk Production webinar by National Milk Producers Federation in conjunction with Dairy Management Inc and McCully Consulting. They looked at the future for milk growth to support capital investments in processing.

Noted was the fact that planned growth in dairy processing tends to locate where milk growth is concentrated. From 2015 through 2024, milk production grew 8% nationwide, but was mostly concentrated in the Southwest, Idaho, and the Upper Midwest (including Michigan, Ohio, Indiana). Of course, Texas was tops, up 65% over the past decade. South Dakota was up 110% but represents less new volume than the Texas gain.

Webinar leaders circled western New York as a subset growth area, pushing the No. 4 state up 14% over the decade, whereas pretty much of the rest of the eastern seaboard was down, including Pennsylvania off by 9% since 2015. Georgia gained 20% trading off for its neighbor Florida, down 21%.

Questions come to mind in these Eastern numbers:

What role did the base programs play? They were installed by most co-ops and some processors and tended to focus on subduing (or even reducing!) production growth on the coasts vs. the interior. They were prevalent over the past decade, until fairly recently.

Industry leaders in the milk production webinar insist the market is signaling for more milk, but producer response has been slow. They said 1 to 2% milk solids equiv. growth via components has helped some, but not enough.

How strong is that market signal for more milk, when dairies are diversifying or exiting? Input costs and milk check deductions have increased over the past decade. The DMC milk-over-feed margin does not tell the whole story. Dairy farmers don’t get a “make allowance” for rising energy, labor, and insurance costs.

Will the 5 to 7 cents/lb increase in make (take) allowances, effective June 1st, dampen what processors describe as their ‘market signal for milk growth’? With the 2025 milk price and DMC margin forecasts already sliding lower, a 5-cents/lb increase in the “make” (take) for cheese translates to about 50 cents off a hundredweight of Class III milk, the nearly 7 cents/lb ‘make’ on dry whey and the interplay of butterfat impacts bump the total Class III ‘take’ to almost $1.00/cwt.

Does THAT signal scream: “More milk please?!” Maybe, if milk check bonuses return and deductions disappear.

(Even if processors bring back milk check bonuses and reduce or erase milk check deductions once they receive the higher take-allowances, how will those milk check adjustments be targeted in terms of dairy farm location, size, type, and/or incorporation of certain ‘sustainability’ technology. We’ll see.)