Opinion/Analysis

By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine (combined 2 part series Aug. 12 and 19, 2022)

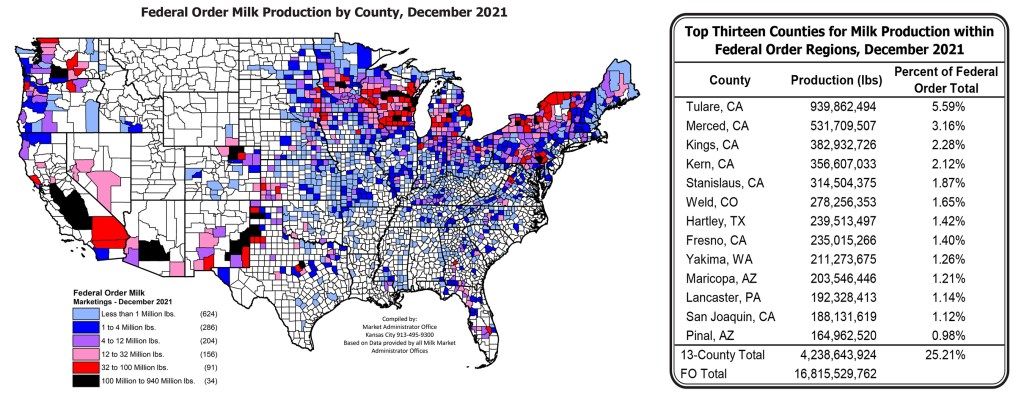

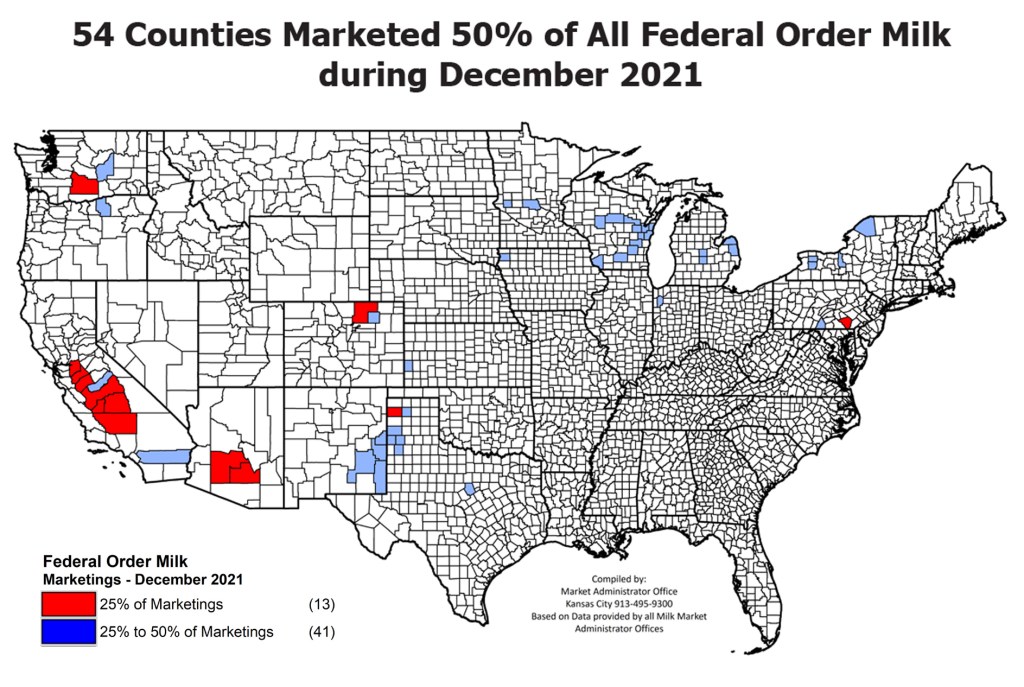

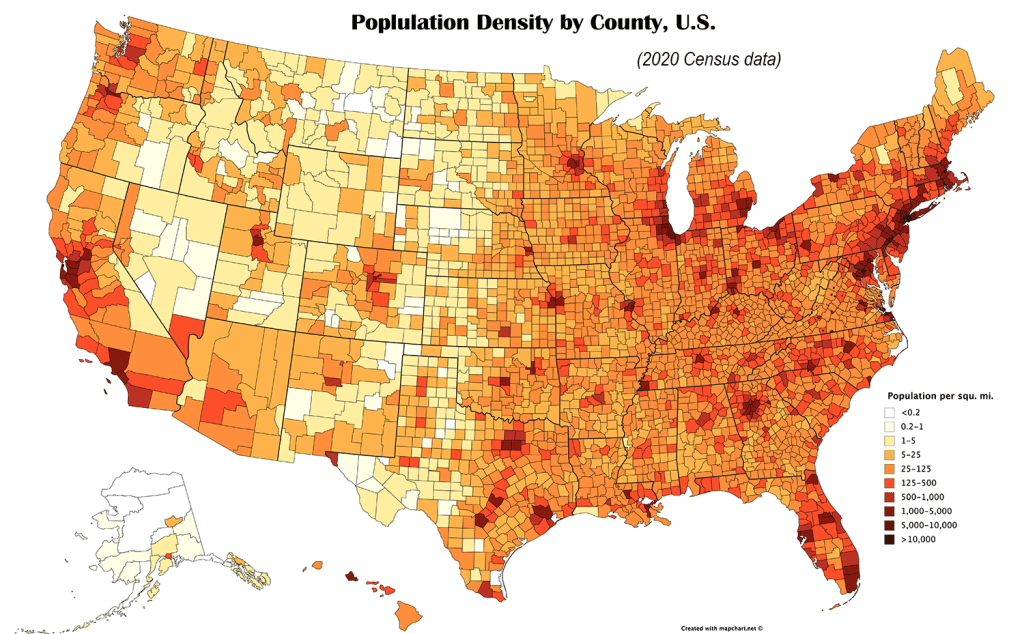

In Class I utilization markets, the landscape is rapidly shifting, and we should pay attention, lest we end up with ‘cow islands’ and ‘milk deserts.’

Farmshine readers may recall in November 2019, I wrote in the Market Moos column about comments made Nov. 5 by Randy Mooney, chairman of both the DFA and NMPF boards during the annual convention in New Orleans of National Milk Producers Federation together with the two checkoff boards — National Dairy Board and United Dairy Industry Association.

Mooney gave a glimpse of the future in his speech that was podcast. (Listen here at 13:37 minutes). He said he had been “looking at a map,” seeing “plants on top of plants,” and he urged the dairy industry to “collectively consolidate,” to target limited resources “toward those plants that are capable of making the new and innovative products.”

One week later, Dean Foods (Southern Foods Group LLC) filed for bankruptcy as talks between Dean and DFA about a DFA purchase were already underway. It was the first domino right on the heels of Mooney’s comments, followed by Borden filing Chapter 11 two months later in January, and followed by three-years of fresh fluid milk plant closings and changes in ownership against the backdrop of declining fluid milk sales and an influx of new dairy-based beverage innovations, ultrafiltered and shelf-stable milk, as well as lookalike alternatives and blends.

The map today looks a lot different from the one described by Mooney in November 2019 when he urged the industry to “collectively consolidate.” The simultaneous investments in extended shelf-life (ESL) and aseptic packaging are also a sign of the direction of ‘innovation’ Mooney may have been referring to.

Two months prior to Mooney issuing that challenge, I was covering a September 2019 industry meeting in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where dairy checkoff presenters made it clear that the emphasis of the future is on launching innovative new beverages and dairy-‘based’ products.

Here is an excerpt from my opinion/analysis of the discussion at that time:

“While we are told that consumers are ditching the gallon jug (although it is still by far the largest sector of sales), and we are told consumers are looking for these new products; at the same time, we are also told that it is the dairy checkoff’s innovation and revitalization strategy to ‘work with industry partners to move consumers away from the habit of reaching for the jug and toward looking for these new and innovative products’ that checkoff dollars are launching.”

These strategy revelations foreshadowed where the fluid milk markets appear to be heading today, and this is also obvious from recent Farmshine articles showing the shifting landscape in cow, farm, and milk production numbers.

When viewing the picture of the map that is emerging, big questions come to mind:

Are today’s Class I milk markets under threat of becoming ‘milk deserts’ as the dairy industry consolidates into ‘cow islands’?

Would dairy farmers benefit from less regulation of Class I pricing in the future so producers outside of the “collectively consolidating” major-player-complex are freer to seek strategies and alliances of their own, to carve out market spaces with consumers desiring and rediscovering fresh and local, to put their checkoff dollars toward promotion that helps their farms remain viable and keeps their regions from becoming milk deserts?

What role is the industry’s Net Zero Initiative playing behind the scenes, the monitoring, scoring, tracking of carbon, the way energy intensity may be viewed for transportation and refrigeration and other factors in Scope 1, 2 and 3 ESG (Environment, Social, Governance) scores?

Shelf-stable milk may provide solutions for some emerging (or are they self-inflicted?) milk access and distribution dilemmas, and maybe one view of ESG scoring favors it? But ultimately it also means milk can come from cow islands to milk deserts — from anywhere, to anywhere.

It also becomes clearer why the whole milk bill is having so much trouble moving forward. The industry machine gives lip-service support to the notion of whole milk in schools, but the reality is, the industry is chasing other lanes on this highway to ‘improve’ the school milk ‘experience’ and ensure milk ‘access’ through innovations that at the same time pave the road from the ‘cow islands’ to the ‘milk deserts.’

It is now clearer — to me — why the Class I mover formula is such a hotly debated topic.

If major industry-driving consolidators are looking to transition away from turning over cow to consumer fresh, local/regional milk supplies by turning toward beverage stockpiles that can sit in a warehouse ‘Coca-Cola-style’ at ambient temperatures for six to 12 months, it’s no wonder the consolidators want the ‘higher of’ formula to stay buried. What a subversion that was in the 2018 Farm Bill.

In fact, if the industry is pursuing a transition from fresh, fluid milk to a more emphasis on shelf-stable aseptic milk, such a transition would, in effect, turn the federal milk marketing orders’ purpose and structure — that is tied to Class I fresh fluid milk — completely upside down.

Landscape change has been in motion for years, but let’s look at the past 6 years — Dean had already closed multiple plants and cut producers in the face of Walmart opening it’s own milk bottling plant in Spring 2018. The Class I ‘mover’ formula for pricing fluid milk — the only milk class required to participate in Federal Milk Marketing Orders — was changed in the 2018 Farm Bill that went into effect Sept. 2018. The new Class I mover formula was implemented by USDA in May 2019, resulting in net losses to dairy farmers on their payments for Class I of well over $750 million across 43 months since then.

(Side note: Under the formula change, $436 million of Class I value stayed in processor pockets from May 2019 through October 2019, alone. DFA purchased 44 Dean Foods plants in May 2019 and became by far the largest Class I processor at that time.)

These and other landscape changes were already in motion when Mooney spoke on Nov. 5, 2019 at the convention of NMPF, NDB and UDIA describing the milk map and seeing plants on top of plants and issuing the challenge to “collectively consolidate” to target resources to those plants that can make the innovative new products.

One week later, Nov. 12, 2019, Dean Foods filed for bankruptcy protection to reorganize and sell assets (mainly to DFA).

Since 2019, this and other major changes have occurred as consolidation of Class I milk markets tightens substantially around high population swaths, leaving in wake the new concerns about milk access that spur the movement toward ESL and aseptic milk. A chain reaction.

What does Mooney’s map look like today after his 2019 call for “collective consolidation” and the targeting of investments to plants that can make the innovative products, the plants that DMI fluid milk revitalization head Paul Ziemnisky told farmers in a 2021 conference call were going to need to be “dual-purpose” — taking in all sorts of ingredients, making all sorts of beverages and products, blending, ultrafiltering, and, we see it now, aseptically packaging?

In addition to the base of Class I processing it already owned a decade ago, the string of DFA mergers has been massive. The most recent acquisitions, along with exits by competitors, essentially funnel even more of the market around key population centers to DFA with its collective consolidation strategy and investments in ESL and aseptic packaging.

The South —

The 14 Southeast states (Maryland to Florida and west to Arkansas) have 29% of the U.S. population. If you include Texas and Missouri crossover milk flows, we are talking about 37% of the U.S. population.

The major players in the greater Southeast fluid milk market include DFA enlarged by its Dean purchases, Kroger supplied by Select and DFA, Prairie Farms with its own plants, DFA and Prairie Farms with joint ownership of Hiland Dairy plants, Publix supermarkets with its own plants, an uncertain future for four remaining Borden plants in the region as Borden has exited even the retail market in some of these states, and a handful of other fluid milk processors.

In Texas, alone, DFA now owns or jointly owns a huge swath of the fluid milk processing plants, having purchased all Dean assets in the Lone Star State in the May 2020 bankruptcy sale and now positioned to gain joint ownership of all Borden Texas holdings through the announced sale to Hiland Dairy.

The Midwest —

Just looking at the greater Chicago, Milwaukee, Green Bay metropolis, the population totals are a lake-clustered 6% of U.S. population. Given the recent closure by Borden of the former Dean plants in Chemung, Illinois and De Pere, Wisconsin, this market is in flux with DFA owning various supply plants including a former Dean plant in Illinois and one in Iowa with Prairie Farms having purchased several of the Dean plants serving the region.

In the Mideast, there is Coca Cola with fairlife, Walmart and Kroger among the supermarkets with their own processing, and DFA owning two former Dean plants in Ohio, two in Indiana, two in Michigan, and a handful of other bottlers.

In the West: DFA owns a former Dean plant in New Mexico, two in Colorado, two in Montana, one in Idaho, two in Utah, one in Nevada and one in California, as well as other plants, of course.

The Northeast —

This brings us to the Northeast from Pennsylvania to Maine, where 18% of the U.S. population lives, and where consolidation of Class I markets, especially around the major Boston-NYC-Philadelphia metropolis have consolidated rapidly against the backdrop of declining fluid milk sales and a big push by non-dairy alternative beverage launches from former and current dairy processors.

DFA owns two former Dean plants in Massachusetts, one in New York, all four in Pennsylvania, one in New Jersey. The 2019 merger with St. Alban’s solidified additional New England fluid milk market under DFA. In 2013, DFA had purchased the Dairy Maid plant from the Rona family in Maryland; in 2014, the prominent Oakhurst plant in Maine; and in 2017, the Cumberland Dairy plant in South Jersey.

More recently, DFA struck a 2021 deal with Wakefern Foods to supply their Bowl and Basket and other milk, dairy, and non-dairy brands for the various supermarket chains and convenience stores under the Wakefern umbrella covering the greater New York City metropolis into New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania. This milk had previously been supplied by independent farms, processed at Wakefern’s own iconic Readington Farms plant in North Jersey, which Wakefern subsequently closed in January 2022.

The long and twisted tale begs additional questions:

As Borden has dwindled in short order from 14 plants to five serving the most populous region of the U.S. – the Southland — what will happen with the remaining five plants in Ohio, Kentucky, Georgia, Louisiana, and Florida? What will become of Elsie the Cow and Borden’s iconic brands and new products?

What percentage of the “collectively consolidated” U.S. fluid milk market does DFA now completely or partially own and/or control?

Will the “collective consolidation” in the form of closures, sales and mergers continue to push shelf-stable ESL and aseptic milk into Class I retail markets and especially schools… and will consumers, especially kids, like this milk and drink it?

What role are rising energy prices, climate ESG-scoring and net-zero pledges and proclamations playing in the plant closures and shifts toward fewer school and retail milk deliveries, less refrigeration, more forward thrust for shelf-stable and lactose-free milk, as well as innovations into evermore non-dairy launches and so-called flexitarian blending and pairing?

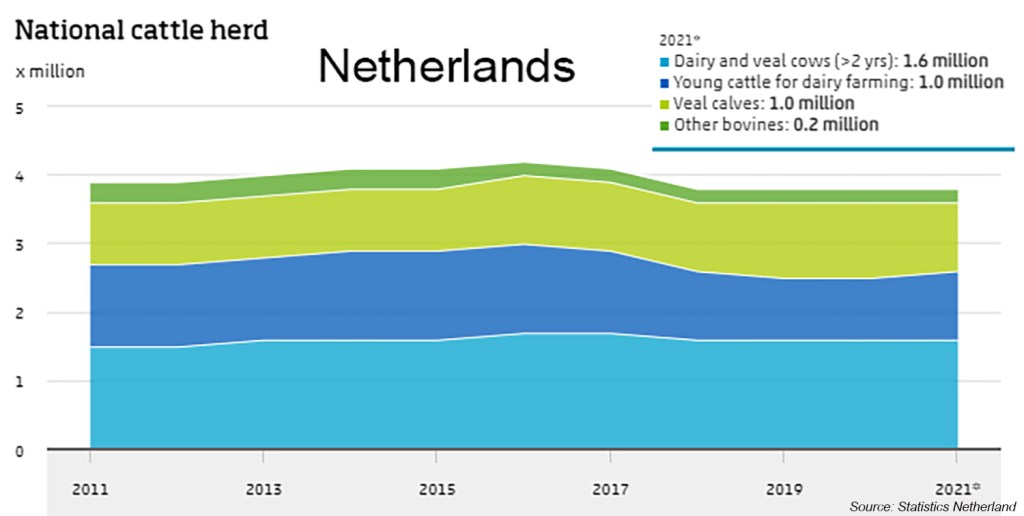

Looking ahead at how not only governments around the world, but also corporations, creditors and investors are positioning for climate/carbon tracking, ESG scoring and the so-called Great Reset, the Net Zero economy, there’s little doubt that these factors are driving the direction of fluid milk “innovation” over the 12 years that DMI’s Innovation Center has coordinated the so-called ‘fluid milk revitalization’ initiative — at the same time developing the FARM program and the Net Zero Initiative.

The unloading of nine Borden plants in five months under Gregg Engles, the CEO of “New Borden” and former CEO of “Old Dean” is also not surprising. Engles is referred to in chronicles of dairy history not only as “the great consolidator” but also as “industry transformer.”

In addition to being CEO of Borden, Engles is chairman and managing partner of one of the two private equity investment firms that purchased the Borden assets in bankruptcy in June 2020. Investment firms fancy themselves at the forefront of ESG scoring.

Engles is also one of only two U.S. members of the Danone board of directors. Danone, owner of former Dean’s WhiteWave, including Silk plant-based and Horizon Organic milk, has positioned itself in the forefront on 2030 ESG goals, according to its 2019 ‘one planet, one health’ template that has also driven consolidation and market loss in the Northeast.

Not only is Danone dumping clusters of its Horizon milk-supplying organic family dairy farms, it continues to heavily invest in non-dairy processing, branding, launching and marketing of alternative lookalike dairy products and beverages, including Next Milk, Not Milk and Wondermilk.

There is plenty of food-for-thought to chew on here from the positives to the negatives of innovation, consolidation, and climate ESGs hitting full-throttle in tandem. These issues require forward-looking discussion so dairy farmers in areas with substantial reliance on Class I fluid milk sales can navigate the road ahead and examine all lanes on this highway that appears to be leading to cow islands and milk deserts.

-30-