By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, October 21, 2022

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — It was intense, productive, enlightening, and at times a bit emotional. And, yes, there was consensus on some key points during the American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) Forum in Kansas City last weekend (Oct. 14-16).

The event was a first of its kind meeting of the minds from across the dairy landscape, involving mostly dairy farmers, but also other industry stakeholders. It was planned by a 12-member committee representing state Farm Bureaus from coast-to-coast, working with AFBF economist Danny Munch.

Farm Bureau president Zippy Duvall kicked things off Friday afternoon, urging attendees to get something done for the future of the dairy industry, to stay cool, leave friendly, and set a pattern for continuing conversations.

“We have the people in this room who I hope can come up with guiding principles,” said Duvall, noting that a meeting like this is something he has dreamed about for years, even prayed for. He talked about his background as a former dairy farmer and assured attendees that milk pricing is a topic he is very interested in.

He challenged the group to come at it with “an open mind. The answers are sitting in this room, not on Capitol Hill. There are some geniuses in this room, people who really understand this system,” said Duvall.

“We all have ideas, and we can lend an ear to other ideas. We learn a lot if we listen to each other,” he said, noting a few of the existing Farm Bureau dairy policy principles: that FMMOs should be market oriented, with better price discovery. They should be fair and transparent, and farmers should be able to understand and compare milk checks.

Hearings not legislation

Duvall noted AFBF agrees with NMPF that future FMMO changes should go through the normal USDA hearing process, not through Congressional legislation. By Sunday, this seemed to be a point of consensus, along with the recognition that FMMOs need updating, but they are still vital for farmers and the industry.

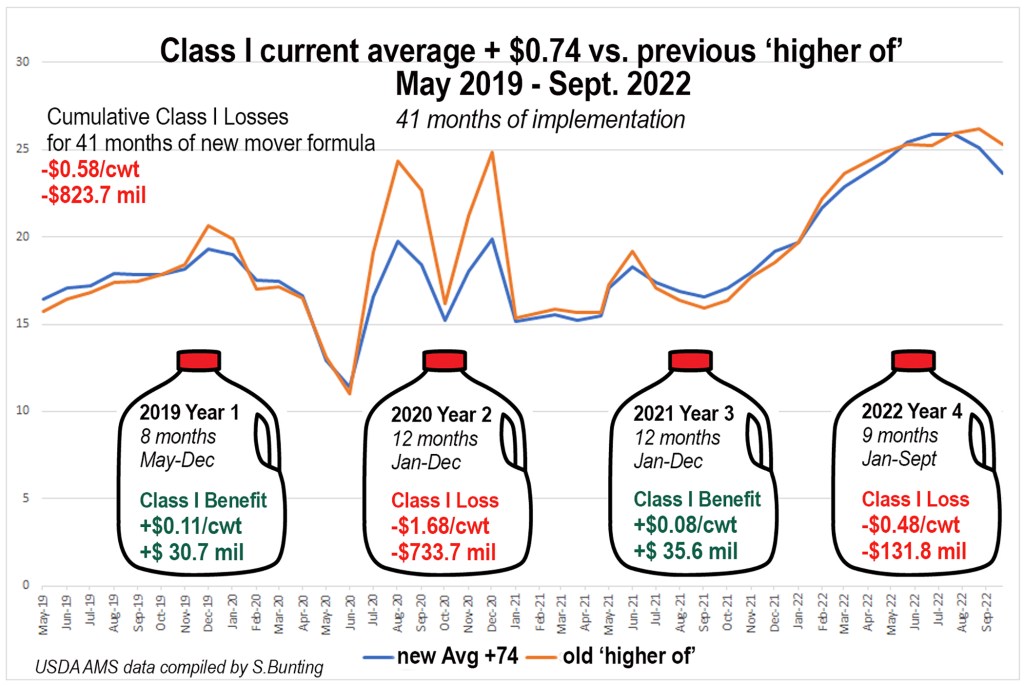

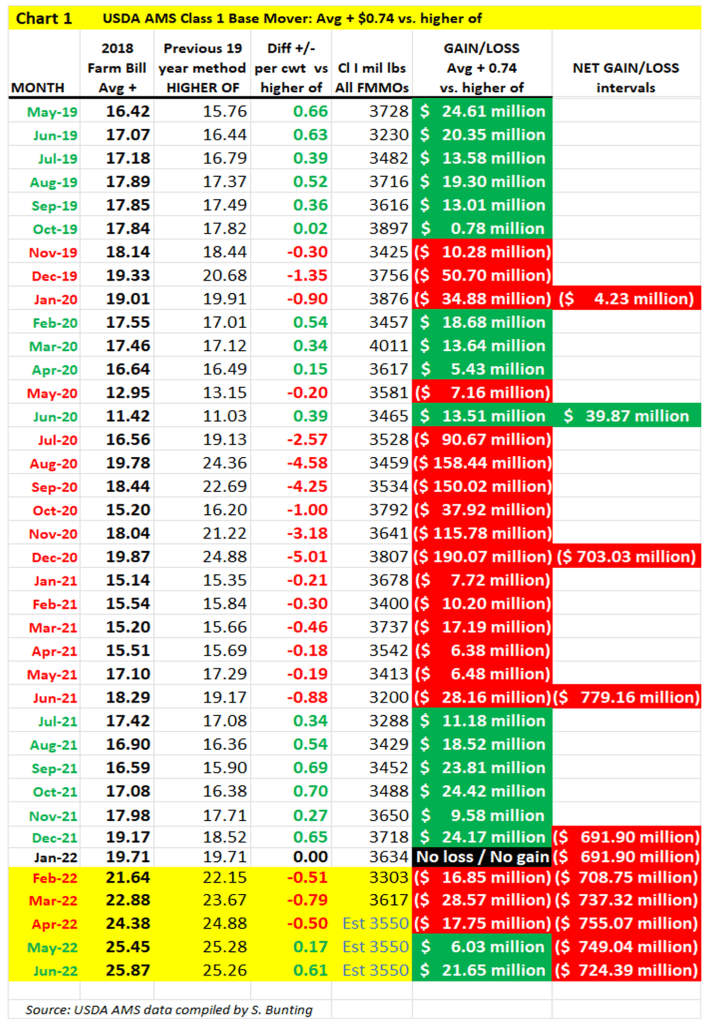

On the Class I ‘mover,’ specifically, Munch noted Farm Bureau already adopted the recommendation through its county, state and national grassroots process to return to the ‘higher of’ — plus 74 cents. The addition of the 74 cents is to make up for the unlimited losses incurred over the past four years.

For NMPF’s part, chief economist Peter Vitaliano and consultant Jim Sleper laid out a series of updates the economic committee’s task force is recommending to the NMPF board, which will vote at the annual meeting at the end of October.

These recommendations include going back to the simple ‘higher of’ for the Class I ‘mover,’ updating make allowances and yield factors, doing a pricing-surface study to update Class I differentials, making changes in the end-product pricing survey to allow dry whey price reporting of sales up to 45 days earlier, not 30 days, and eliminating the 500-pound barrel cheese sales from the Class III cheese price formula to base it only on the block cheese.

Intense, informative, valuable

The three days were intense, covering a lot of information, and were shepherded by expert panels and ‘cat herder in chief’ Roger Cryan, AFBF’s chief economist since October 2021.

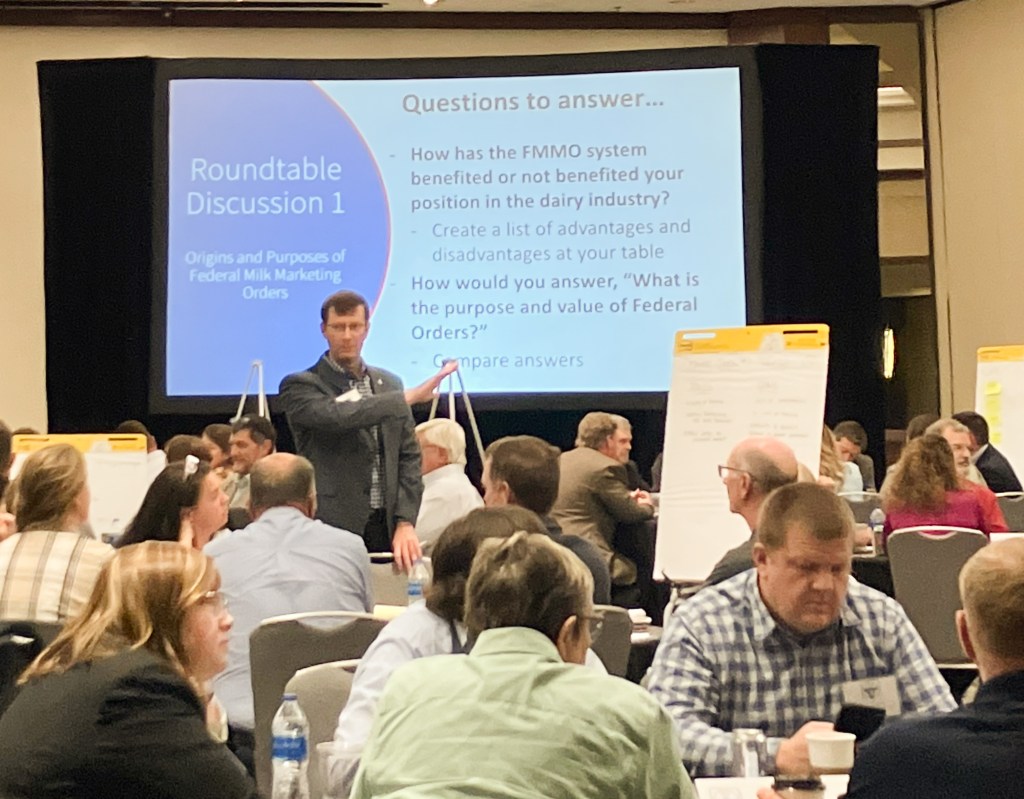

Munch served as the emcee — akin to the ghost of milk pricing Past (Friday), Present (Saturday) and Future (Sunday). He introduced the various panels and provided economic snapshots and questions for the 25 breakout tables to discuss, decide and deliver.

Meeting organizers reshuffled the deck of 200 attendees from 36 states and representing nearly 150 state and national producer organizations, Farm Bureau chapters, regulatory agencies, farms, co-ops, processors, financial and risk management firms, and university extension educators.

Attendees were assigned tables with a number on the back of each name tag. The goal was to mix the table-groupings for varied geographic and industry perspectives. Each table was equipped with its own large flip tablet mounted on an easel.

According to Munch, Farm Bureau will scan and collate the information from all of the large tablets and issue a preliminary report to attendees followed by a public report later this year.

On Sunday, the open microphone was lively and most tables reported from their flip tablets. Overwhelmingly, attendees said they found value in the meeting and appreciated the platform. They reported a desire to keep the conversations going, to do this again, not just every 20 years, and not just in response to a problem, but to be forward-looking with the many challenges on the dairy horizon.

Platform for next big issue

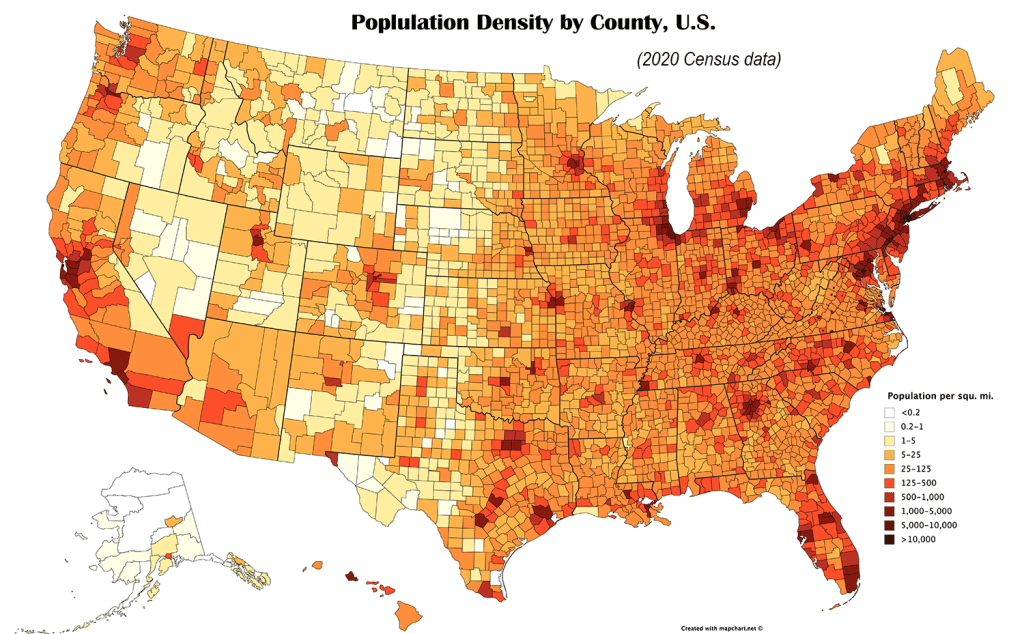

For example, Gretl Schlatter, an Ohio dairy producer on the board of American Dairy Coalition (ADC) noted that only Class I milk is mandated to participate in FMMOs, and that today, the FMMOs are weakened with only 60% of U.S. milk production participating in the revenue-sharing pools.

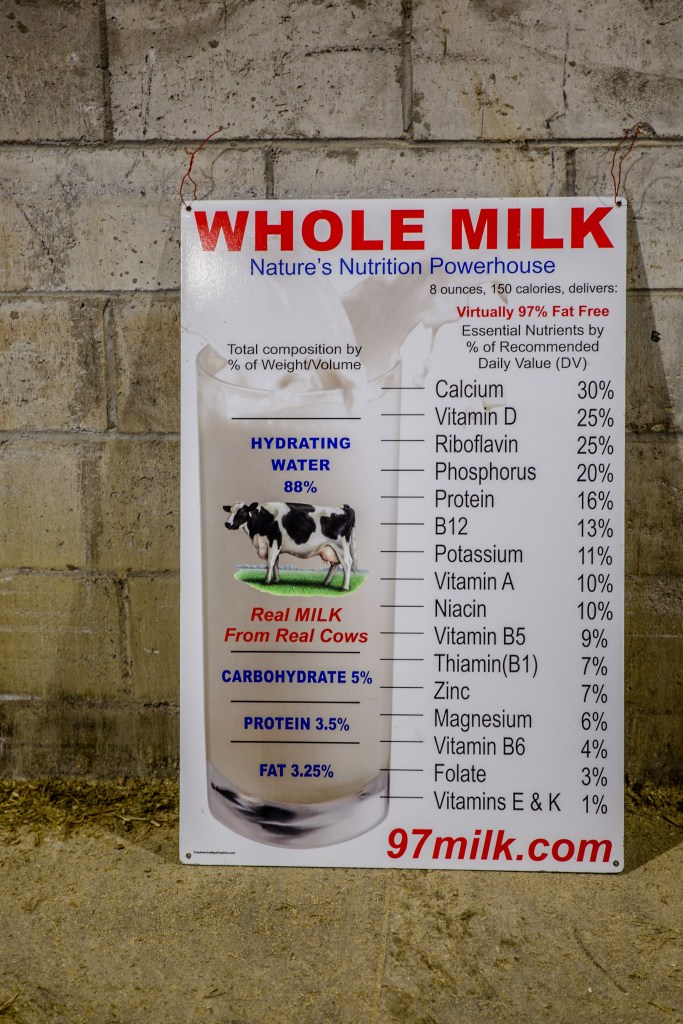

“Where will we be in five years? We do not want to give up on fluid milk – our nutrition powerhouse,” she said. “The issue now is federal milk pricing but the next one coming — fast — is the sustainability benchmarks, the climate scores. We need to keep meeting like this as an industry, keep talking to each other, and get ready for the next big thing affecting our farms and family businesses.”

This was touched upon by Duvall and others, but Cryan reminded everyone that, “Federal Orders are complicated enough without adding the sustainability discussion to it.”

Duvall reminded attendees that this meeting was Farm Bureau’s response to the words of Ag Secretary Tom Vilsack last year, when he said there would be no USDA hearing until the dairy industry reaches some “consensus” on solutions.

This set into motion an already dairy-active Farm Bureau that had formed its own task force, responding to grassroots dairy policy coming up from the county and state levels to national through AFBF’s grassroots process.

In fact, NMPF’s Vitaliano, noted that, “having Roger Cryan at Farm Bureau makes it easier to do this,” to partner on formulating dairy policy because of his background. Prior to coming to Farm Bureau a year ago, Cryan was an economist for NMPF and then for USDA AMS Dairy Programs.

The first hour of the first day included a recorded message from Secretary Vilsack and an in-person presentation by Gloria Montano Green, USDA deputy undersecretary for Farm Production and Conservation.

They encouraged attendees to work together and told them what the Biden-Harris administration has done and is doing for dairy. Primarily, they went through a list of funding and assistance, including the improved Dairy Margin Coverage, the PMVAP payments, Dairy Revenue Protection, Livestock Gross Margin, dairy innovation hub grants and the recent funding for conservation and climate projects that includes 17 funded pilots involving dairy.

They told attendees that the dairy industry is “far ahead” on climate and conservation because it has been involved in these discussions and is already mapping that landscape.

Dana Coale, deputy administrator of USDA AMS Dairy Programs, took attendees through the FMMO parameters. She engaged with the largely dairy farmer crowd in a frank discussion of what Federal Orders can and cannot do. The headline here is that this current time period before a hearing is a time when she and her staff can talk freely and give opinions. Once a hearing process begins, she and her staff are subject to restrictions on ex parte communications.

Consensus to go back to ‘higher of’ formula

If there was one FMMO “fix” that achieved a clear consensus and was given priority, it was support for going back to the Class I ‘mover’ formula using the ‘higher of’ Class III or IV skim price instead of the current average plus 74 cents method that was changed in the 2018 farm bill.

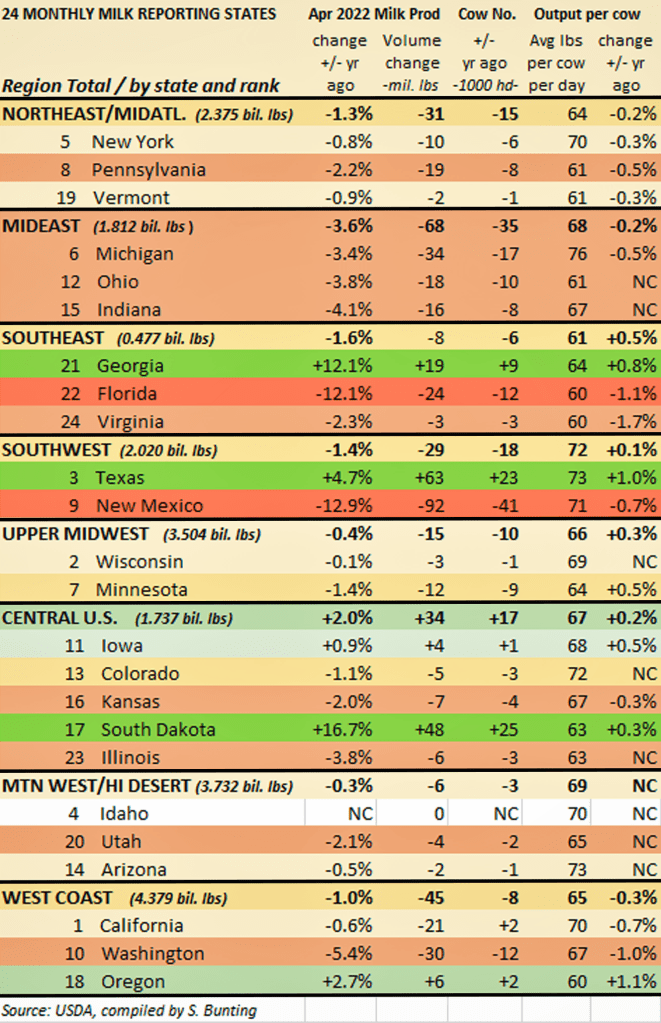

Since implementation in May 2019 through October 2022, the new method will have cost dairy farmers $868 million in net reduced Class I revenue, which further erodes the mandatory Class I contribution to the uniform pricing among the 11 Federal Milk Marketing Orders (FMMO), setting off a domino effect that has led to massive de-pooling of milk from FMMOs and decreased Federal Order participation.

During his presentation Friday, retired Southeast Milk CEO, Calvin Covington, said dairy farmers lost $69 million in revenue for the first 8 months of post-Covid 2022, alone. That figure will rise to an estimated $200 million when September and October Class I milk pounds are tallied.

Noting NMPF’s task force recommends the board approve petitioning USDA to go back to the ‘higher of,’ Vitaliano cited “asymmetric risk” as the reason.

This risk scenario was also explained by others. ADC’s Schlatter, for example, noted the current averaging formula “caps the upside at 74 cents, but the downside is unlimited.”

Vitaliano noted that whenever there is a ‘black swan’ event or new and different market factors, this downside risk becomes unacceptable for farmers, and he indicated these market events that create wide spreads in manufacturing classes are likely to continue into the future.

Dr. Marin Bozic, University of Minnesota assistant professor of applied economics, observed the way this downside ‘basis’ risk becomes unmanageable via new and traditional risk management tools. In his futuristic talk on Sunday, producers asked questions, to which he responded that, “Yes, farmers show me that they can’t use the Dairy Revenue Protection because of this basis risk.”

Bozic is also founder and CEO of Bozic LLC developing and maintaining the intellectual property for risk management programs like DRP.

He also spoke about the concerns of the Midwest as FMMO participation declines.

Presenting his own ideas and separately the ideas of Edge Dairy Farmer Cooperativ, Bozic said Edge is seeking a consensus to support two or three lines in the upcoming farm bill to simply “enable” FMMO hearings to introduce flexibility on an Order by Order basis, so that uniform benefits can be shared instead of a uniform price. Flexibility, they believe, would enable new ‘uniform benefits’ discussion that can help maintain or encourage FMMO participation in marketing areas with low Class I utilization.

Early in the Class I formula loss scenario of 2020-21, Edge had suggested a new Class III-plus formula to determine the ‘mover.’ Bozic said that “the idea of returning to the ‘higher of’ is not a deal breaker for Edge in the short-term.”

Even Mike Brown, senior supply chain manager for Kroger, unofficially indicated IDFA “could be open to the idea” of reverting back to that previous ‘higher of’ formula. As dairy supply chain manager on everything from Kroger’s milk plants to its new dairy beverages, cheese procurement, and so forth, Brown was asked if the averaging formula allowed him to ‘hedge’ fluid milk to manage risk as a processor.

The answer? Not really. Brown said there are ways for processors to manage risk under the ‘higher of’ formula also, but that they haven’t done any hedging under the averaging formula with fresh fluid milk – and very little risk management with their new aseptically packaged, shelf-stable milks and high protein drinks.

Incidentally, he said, the aseptic, ultrafiltered, shelf-stable dairy beverage category “is growing faster than plant-based” in their retail sales.

This exchange and other discussions suggested the averaging formula may have been geared more toward price stability that would encourage processors to invest in expensive aseptic, ultrafiltered and shelf-stable milk-based beverage technologies that result in a storable product needing risk management.

Fresh fluid milk is already advance-priced and quite perishable with a fast turnaround. Aseptic, ultrafiltered and shelf-stable products, on the other hand, can be packaged under one set of raw milk pricing conditions and sold to retail or consumers up to nine months later under another set of raw milk pricing conditions.

Frankly, it appears that the consumer-packaged goods companies (CPGs) may be driving such shifts, just as we heard from Phil Plourde of Blimling/Ever.Ag that CPGs are “all-in” on the climate scoring — the next big thing on the dairy challenge list.

Tacking de-pooling – regional or national?

Attendees came back to the specific concern about de-pooling, which Vitaliano and Cryan both described as an issue to be handled regionally and not through a national hearing.

This did not seem to satisfy some who raised the concern. Toward the conclusion Sunday, Cryan explained it this way:

“De-pooling is a national issue in principle but a regional issue in detail. Every region will have different ideas, needs and situations. If there is consensus (on pooling rules) in a region, then changes could move forward quickly,” he said.

Make allowances are sticky wicket

Attendees appeared to agree that make allowances should be addressed or evaluated through a hearing, but ideas on how to handle this sticky-wicket varied.

Attendees questioned panelists, pointing out that if a farmer’s profit margin on milk is only around $1.00 per hundredweight, then raising make allowances an estimated $1.00 per hundredweight is going to be a tough pill to swallow.

Vitaliano said NMPF is commissioning an economic study with their go-to third-party economist Scott Brown at University of Missouri to show the actual milk check impact of raising make allowances that are embedded into the end-product pricing formulas for the four main products: cheddar, butter, nonfat dry milk and dry whey.

He said the discussions about make allowances as a cost to farmers are “purely arithmetic” but that the “true impact” is not a straight math calculation. Instead, he said, when make allowances are set appropriately, dairy producers ultimately benefit, so in his opinion, it’s not a penny for penny subtraction.

Several other panelists and attendees observed that processors and cooperatives have been creating their own ‘make allowances’ through assessments, loss of premiums, and other milk check adjustments.

Vitaliano stressed that when make allowances are set properly, the industry is stronger and better able to compensate producers. Initially, he said, raising make allowances would have a negative impact on expansion, which in turn would have a positive impact on producer prices.

When asked if raising make allowances would mean lost premiums would return to farmer milk checks, he responded by saying “that depends, and it won’t happen right away.”

In other words, raising make allowances will be painful in the short term, but in the long-term (to paraphrase) that pain leads to gain.

Some panelists and attendees referenced an idea of “phasing in” a future raise in make allowances.

Others wondered why it is necessary with the amount of innovation happening in the 15 years since they were last raised as processors make a wider variety of dairy products – not just those bulk items that are surveyed for end-product pricing formulas.

One idea suggested by a Wisconsin dairy producer was to tie make allowance increases to plant size — much the same way that dairy farmers are only assisted up to a production cap of 5 million annual milk pounds. Cryan said he heard a similar proposal previously to use a graduated scale for make allowance increases according to plant size and presumably age.

This is the crux of the make allowance issue because the new state of the art plants produce many types of products, both commodity and value-added; whereas some of the smaller and older plants that are still vital to the dairy industry are more apt to specialize in producing a bulk commodity with a more limited foray into value-added non-surveyed products.

Modified bloc voting?

While there appeared to be consensus that changes to the FMMOs should be done by USDA petition through the administrative hearing process, not through Congressional legislation, some of the discussion at tables and the open-microphone noted the importance of a producer vote after hearings and USDA final decisions. Many felt farmers should have an individual vote on FMMO changes.

Currently, cooperatives bloc vote for their members to assure that FMMOs are not ended inadvertently by lack of producer interest in following-through on a vote.

One compromise suggested by Bozic was to have a preliminary non-binding vote by individual producers, followed by the binding vote done in its usual way.

This, he said, would at least increase accountability and transparency in the FMMO voting process and bring producer engagement into the FMMO hearing process. To be continued

-30-