Cheese and whey, will continue driving bus, with big growth in processing capacity on the road ahead

By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, Feb. 7, 2025

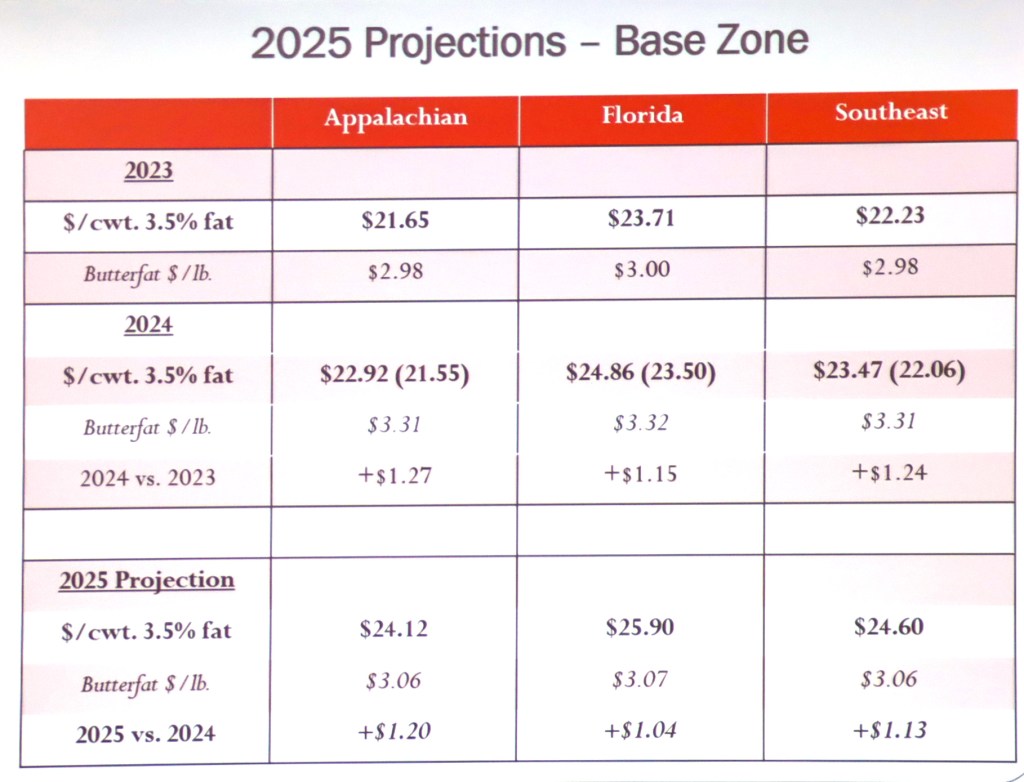

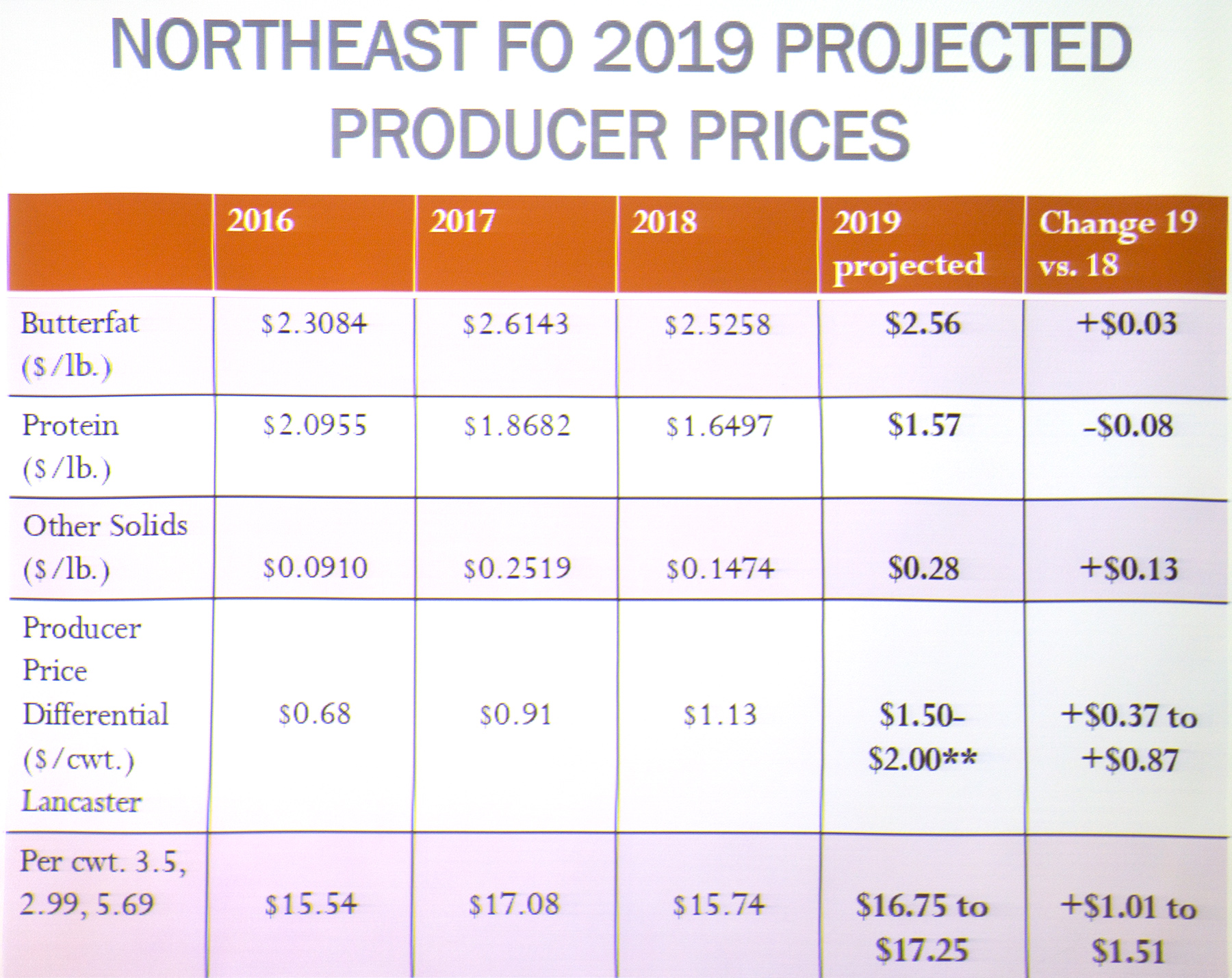

EAST EARL, Pa. – Looking at the milk markets for 2025, Calvin Covington sees farm-level milk prices in the Northeast averaging 25 to 75 cents per hundredweight higher this year. He said milk margins, nationally, averaged $11.86 for the first 11 months of 2024, and he expects similar good margins to prevail in 2025.

The caveat? These are forecasted averages, and farmers should expect price volatility in their income and input costs, along with the mixed bag of positive, negative, and unknown impacts from the Federal Milk Marketing Order changes implemented in the second half of the year. He expects butterfat prices to remain good, but lower in 2025; whey prices will be higher, but more volatile; and protein may be lower as huge new cheese processing capacity comes online

Covington mostly shared what’s on his radar for the next 3 to 5 years during R&J Dairy Consulting’s 18th Annual Dairy Seminar, attended by more than 250 farmers at Shady Maple Smorgasbord in eastern Lancaster County, Pennsylvania on Jan. 28th.

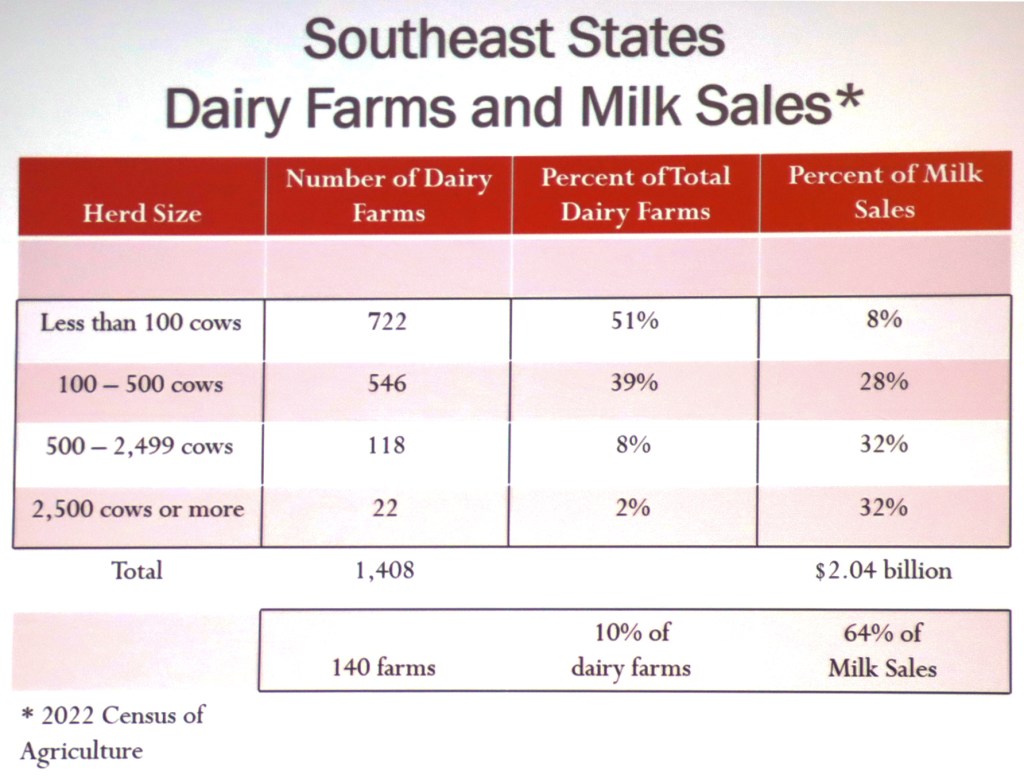

He remarked about the number of young farmers in the crowd, and pointed out that Lancaster County is the consummate dairy county in the U.S. — with more than 1100 Grade A dairies, producing over 2 billion pounds of milk last year, which is 4.5% of total U.S. output and more milk than half of the state totals across the nation.

Consumers: more cheese, more fat, more solids

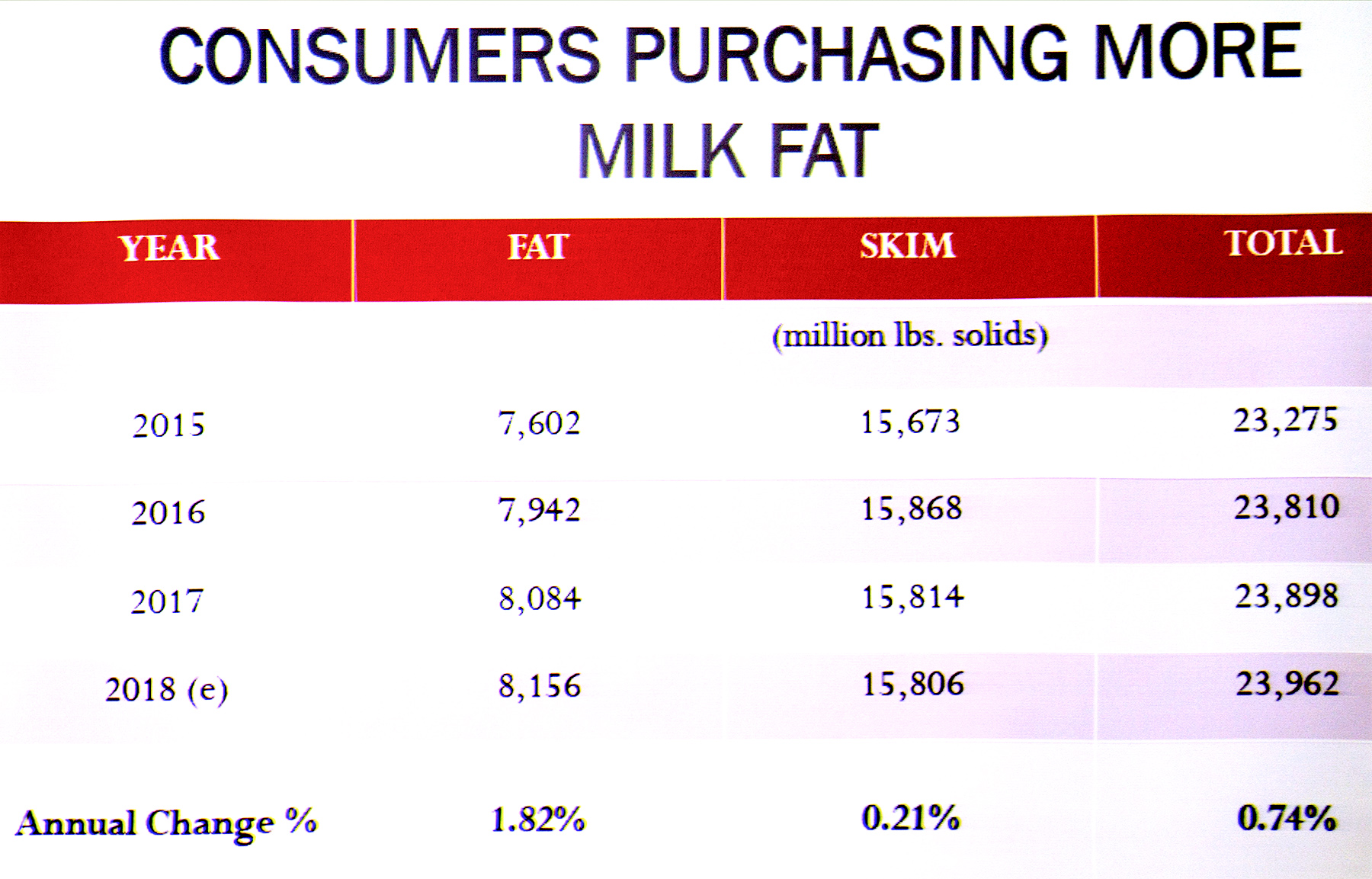

“Cheese is driving the dairy industry, and consumers are consuming more milkfat. That’s what makes stuff taste good,” he said. “Cheese is one-third fat, and that’s one reason why milkfat consumption is growing.”

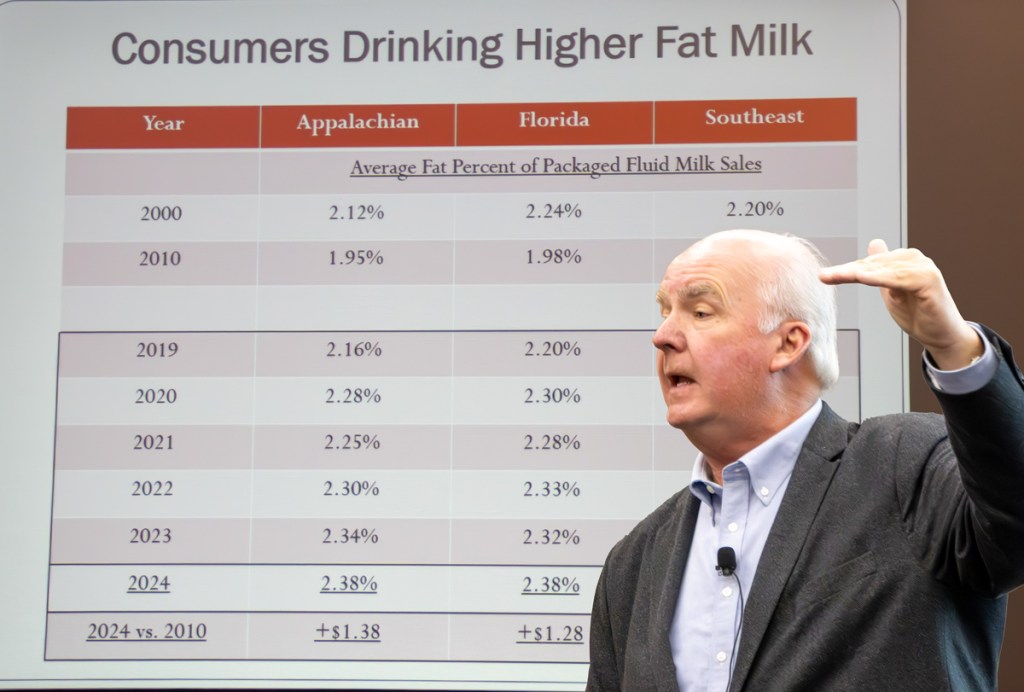

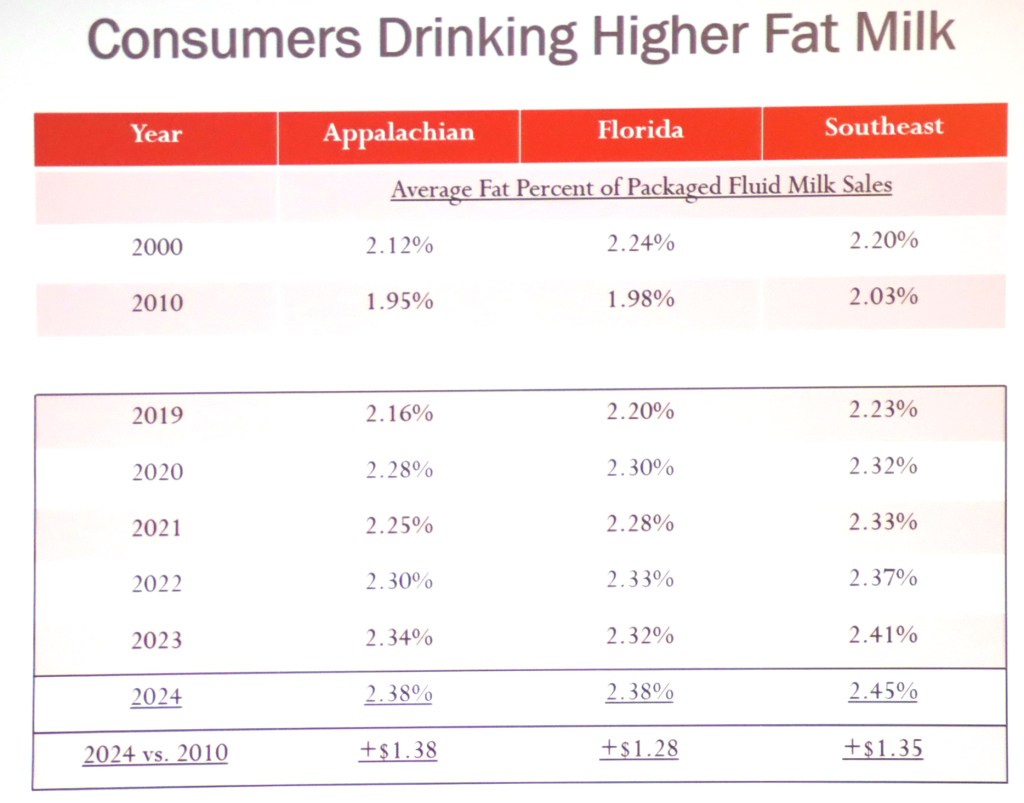

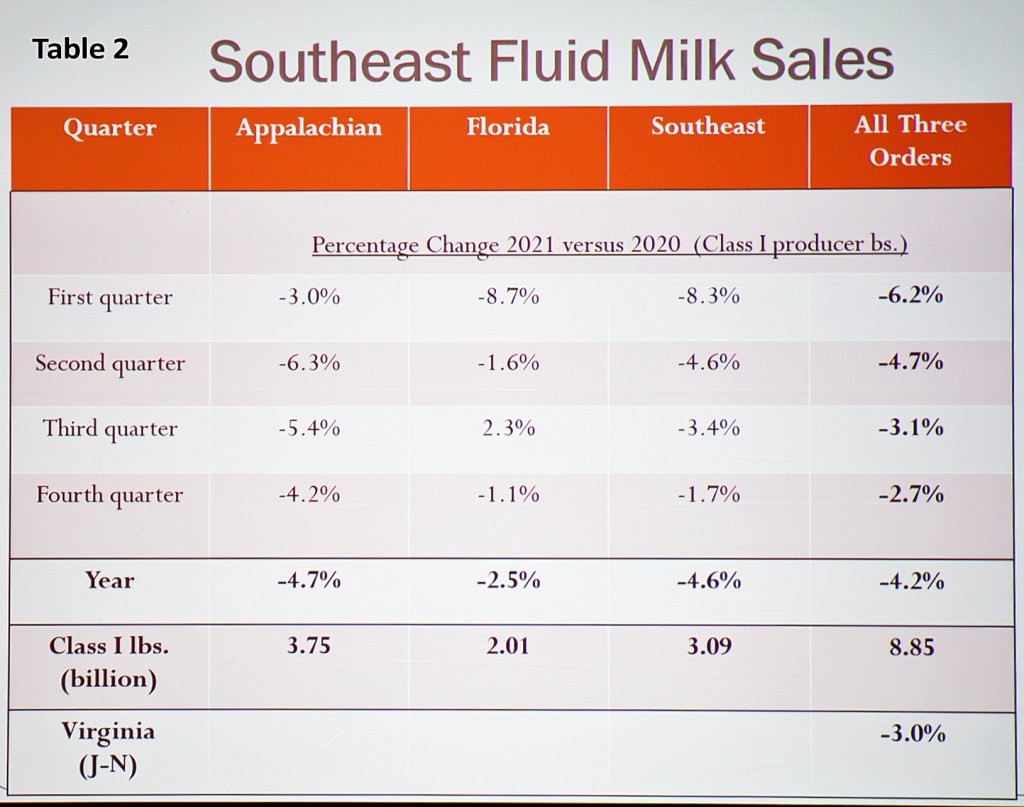

He also showed how increased fat consumption is demonstrated in fluid milk sales, with “whole milk coming up.”

This trend toward consuming products with more solids is also evident in ice cream sales, which are down, but the fat content is up; and in yogurt sales, which are flat, but move “more milk in the yogurt” in the form of more solids.

Now retired, Covington, a previous National Dairy Shrine Guest of Honor and World Dairy Expo Person of the Year, spent over 50 years working for dairy farmer organizations, including as a DHIA milk tester, CEO of American Jersey Cattle Breeders Association, and CEO of Southeast Milk Inc.

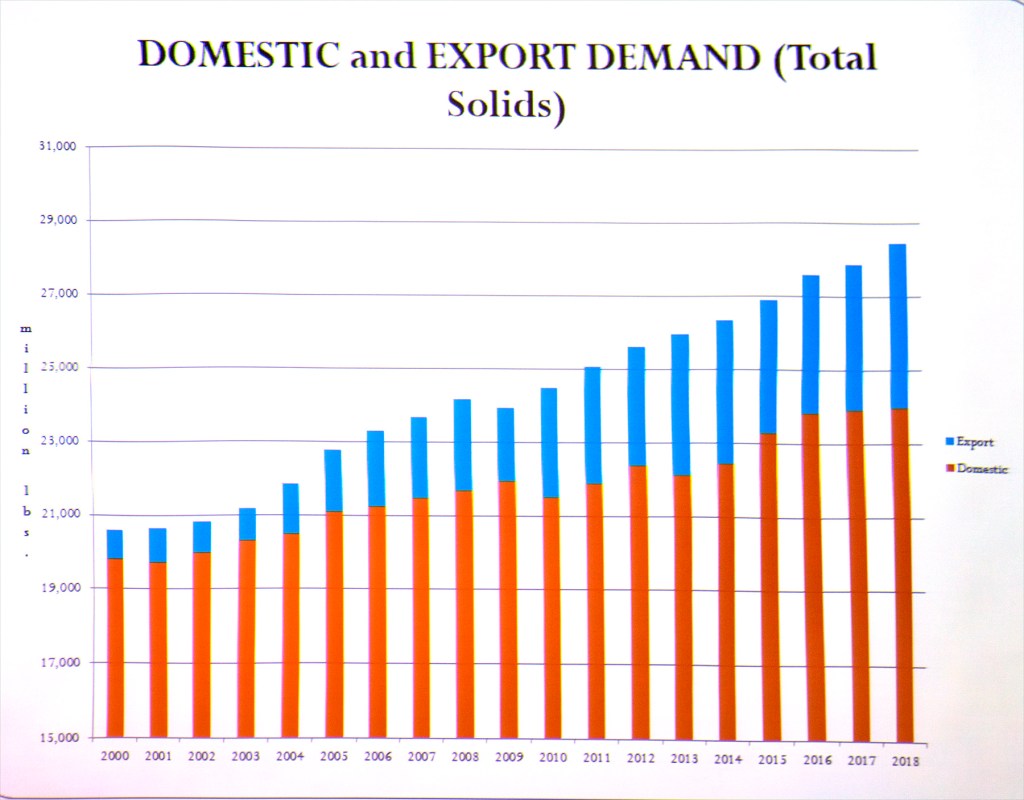

He said the total solids growth in the dairy sales is expected to continue, up from 27 billion pounds total a decade ago to 31 billion pounds in 2024.

The caveat, he said, is that “exports peaked a couple years ago at 17% of total milk solids, and last year (2024) was down at 16%. Exports are a big part of your market, but they have started to level off.”

When asked about imports, Covington said “they keep going up, especially on butterfat” as the U.S. now imports almost as much milkfat as it exports.

He noted increased consumer demand for Irish butter, which is made differently than U.S. butter, with more butterfat. “I hope we start making better-tasting butter in the U.S. instead of importing it,” he shared.

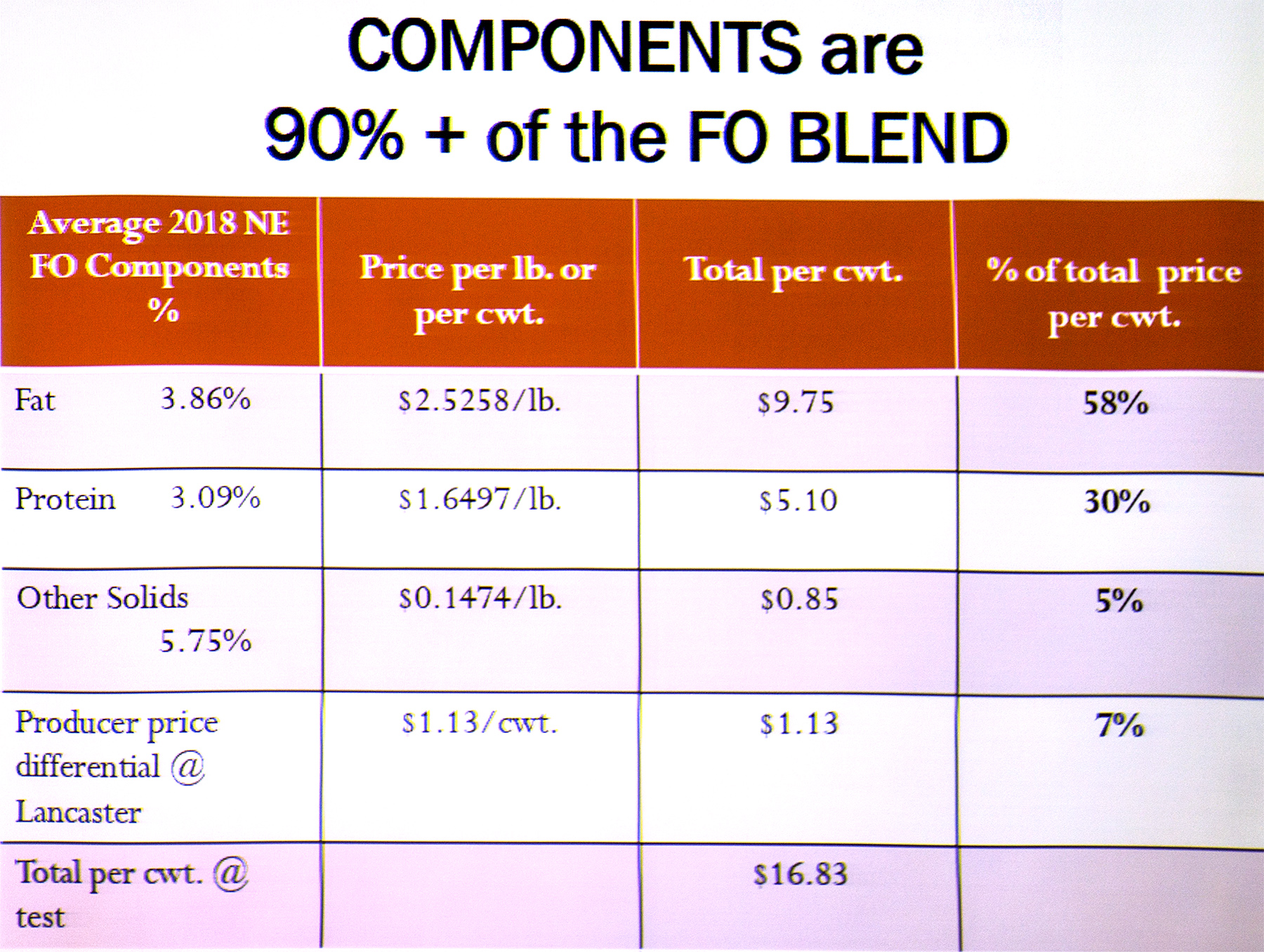

Amid the demand for milk solids, Covington said “it’s amazing what you are doing with your milk components as dairy farmers.” In the Northeast, producers are averaging 4.21 fat and 3.29 protein due to genetics and “the job farmers are doing with their nutritionists and feed companies.”

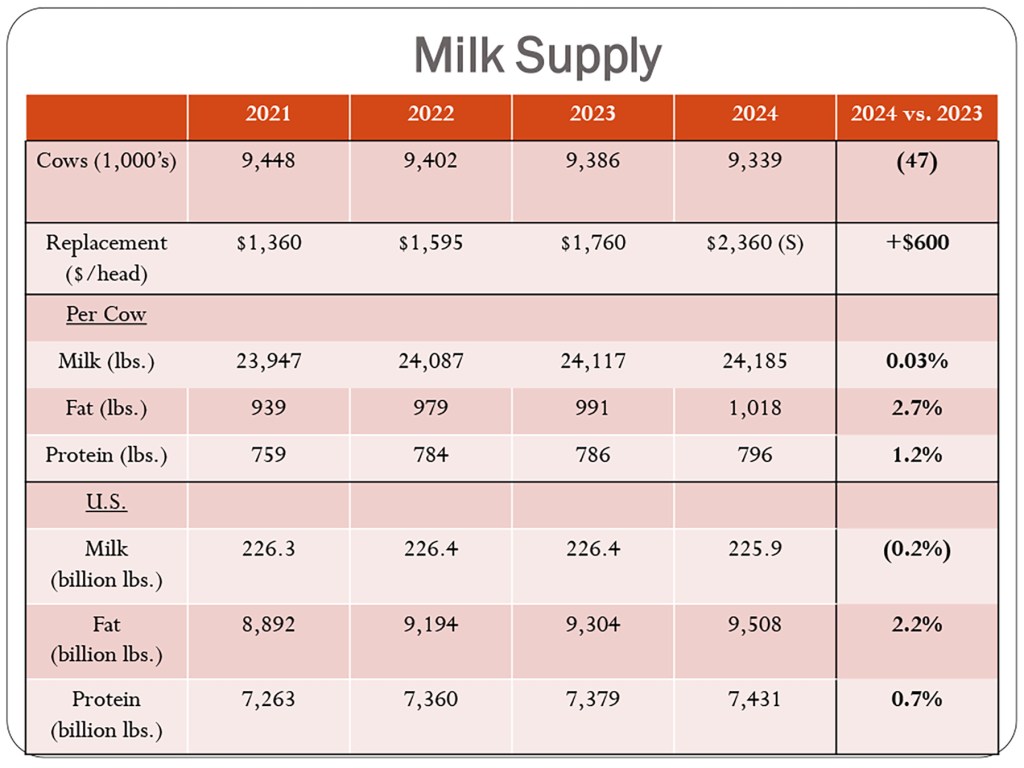

Components are the big story on the supply side, a trend he also sees continuing. He doesn’t expect dairy cow numbers nor milk output per cow to go back to the year-over-year gains seen in the past any time soon.

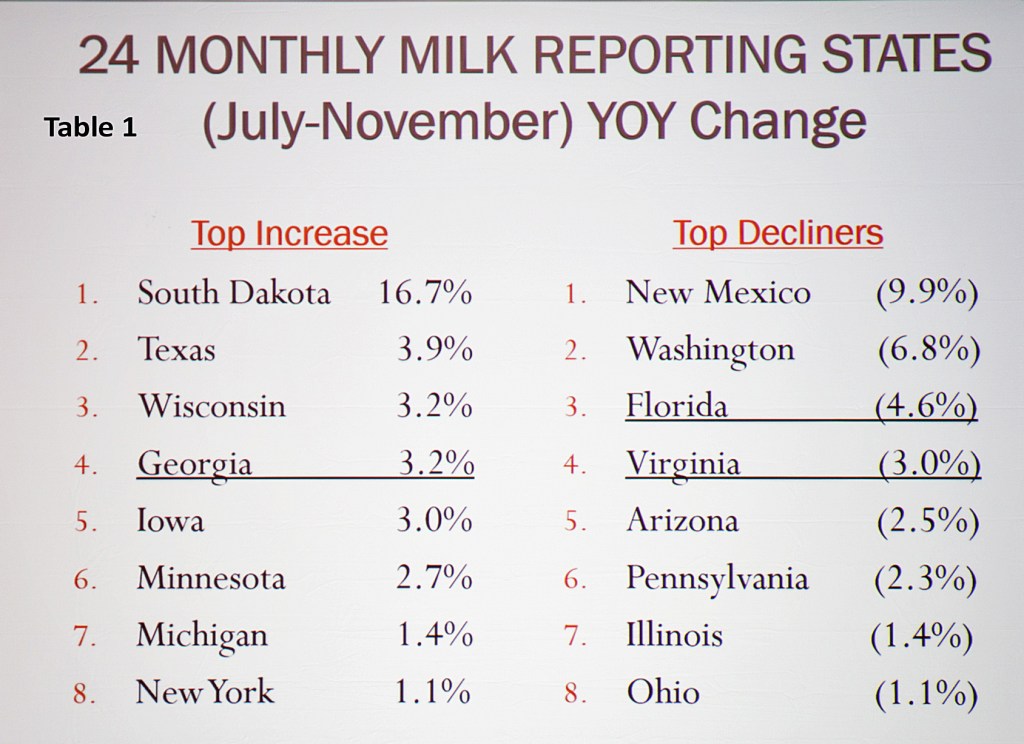

With a chart he showed the stark 2024 vs. 2023 data: Cow numbers are down 47,000 head; replacement heifers sell for $600 more per head; average milk output per cow is flat; but average fat pounds per cow is up 2.7% and average protein pounds per cow up 1.2%. This means that even though total U.S. milk production at an estimated 225.9 billion pounds is down 0.2% from year-earlier, total fat pounds at 9.508 billion pounds are up 2.2%, and protein pounds at 7.431 billion pounds up 0.7%.

“You’re doing it with your components,” he said. “And that’s going to continue.”

Cheese (or maybe whey) is driving the bus

Putting aside the import and export caveats, Covington demonstrated that as the overall dairy market is growing, almost all of this growth has been in the cheese market, which has become a much bigger piece of the much bigger pie.

“Cheese has been driving the dairy industry for several years, and everything points to it driving the industry going forward,” he said, showing a chart of the product mix in the year 2000 when 167.4 billion pounds of milk was produced in the U.S., sold as half cheese, and one-third fluid milk, with 15% other products. This compares with 2024, when 225.9 billion pounds of milk was produced and 58% of the sales were in cheese, 20% fluid milk, and 22% other products.

Per capita trends also show “consumers are eating more of their milk instead of drinking it,” said Covington. “We have seen tremendous change since 1986, when consumers first started consuming more of their milk as cheese than as fluid milk. Look at 2023, people consumed 405 pounds of milk (equivalent) in the form of cheese and 128 pounds in the form of fluid milk.”

While home milk delivery is rare today, Covington said it happens now in the form of pizza.

“If I drive around the city on a Friday night, I’ve got to get out of the way of the pizza delivery people. I figure, on average, it takes a little over a gallon of milk to make one average size pizza. Just think how much home delivery we have today of milk, but in the form of something else, not the milkman dropping off half gallons,” he said.

“The market is changing, and it’s going to keep on changing.”

Why is cheese growing so much? Covington pointed to things he hopes are lessons for other products: 1) Convenience, innovation in packaging and varieties, with pizza accounting for 42% of all cheese; 2) Brand identity, there’s still a lot of this in cheese, not making it a commodity to try to get to the lowest price like in other dairy products (i.e. fluid milk); and 3) taste, people love cheese.

Big bets on the future

Big bets are being made for more cheese growth, and the revenue stream of whey ‘byproduct.’

“We are in a slurry right now of a pile of money being spent on new plant construction,” said Covington, listing the states of Kansas, Texas, South Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin and New York.

When all of this new construction is complete over the next year or so, Covington expects the need for 30 million pounds of milk a day to fill the new plants or expansions, which he estimates represent investments of at least $5 billion and are owned by private companies or groups of farmers or individual farms that are not cooperatives.

“This kind of money and growth is not being put out there unless there is confidence in getting a return on investment with cheese and whey product growth both domestically and internationally,” he pointed out.

These new plants making all of this cheese will also have a lot of whey.

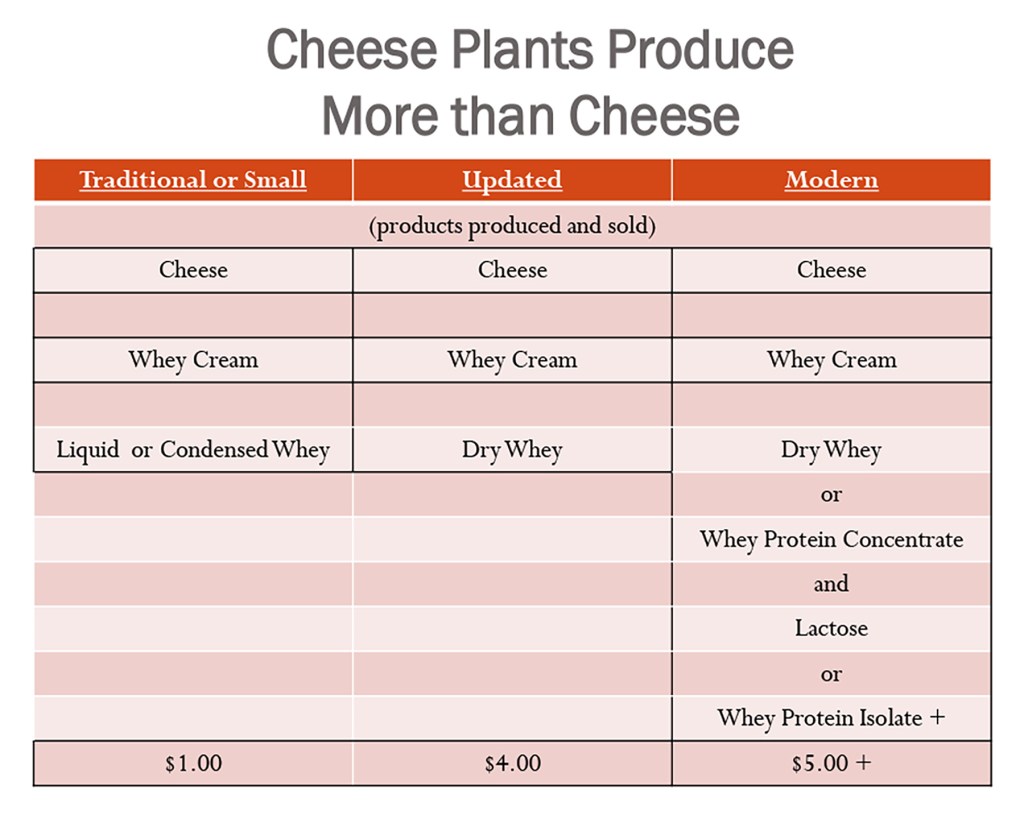

He explained that small plants get about $1.00/cwt for the whey cream and have the liquid whey to do something with. Some plants might dry it and get $3 per cwt for the dry whey plus the $1 for the whey cream, so that’s $4/cwt.

“Small traditional cheese plants can’t afford the equipment to do what some of these new plants are doing. These new companies not only dry the whey, they fractionate it to make whey protein concentrates. They separate out the lactose for whey protein isolates,” Covington said, rattling off a few items on the expanding list for everything from snacks and beverages, to pharmaceuticals and cosmetics, to milk replacers, to counter-top items, ‘pizza cheese,’ artificial seafood, canned hams, and more.

“It’s just amazing, and it brings in more revenue. When we think about cheese, it’s more than just the cheese, it’s also the income from the whey that’s left over,” he said, adding that the CEO of a large cheese company once told him: “Sometimes I think the cheese is the byproduct.”

With this kind of investment, the new plants are going to be making big volumes and getting income from the whey.

“This puts a crimp on the small cheese plants that can’t do this, and they’re going to have to get it out of the cheese end,” Covington observed, suggesting some potential structural change on the cheese side of the dairy industry with significant domestic and international sales growth needed to stay a step ahead.

On the positive side of the fluid milk industry, in addition to growing whole milk sales, Covington highlighted new investments. He sees a future with more dominance by grocery stores, pointing out the two new Walmart plants going into Georgia and Texas, which will be the largest in the country, processing 50 to 55 loads of raw milk a day.

Other big investments in the fluid milk sector in the Northeast are ultrafiltration and ESL packaging, such as the new fairlife plant under construction in western New York, new ESL expansion at the former Hood plant owned by Maola, and aseptic shelf-stable milk packaging at Cayuga Milk Ingredients.

-30-