By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, January 24, 2025

SAVANNAH, Ga. – Flat milk production volume, but with higher components, and a more unpredictable demand are factors new to the dairy industry that make price projections more difficult for the year ahead.

Calvin Covington has spent his life in milk marketing, now retired from managing Southeast Milk Inc., and before that working with cheese processors to see (and pay) the value of higher protein and fat when he was with the American Jersey Cattle Association earlier in his career.

Covington gave his dairy outlook for 2025, with emphasis on the Southeast markets during the Georgia Dairy Conference attended by over 400 in Savannah, Jan. 20th.

“I was way low on my projections last year. 2024 ended up with prices higher than anticipated,” he said.

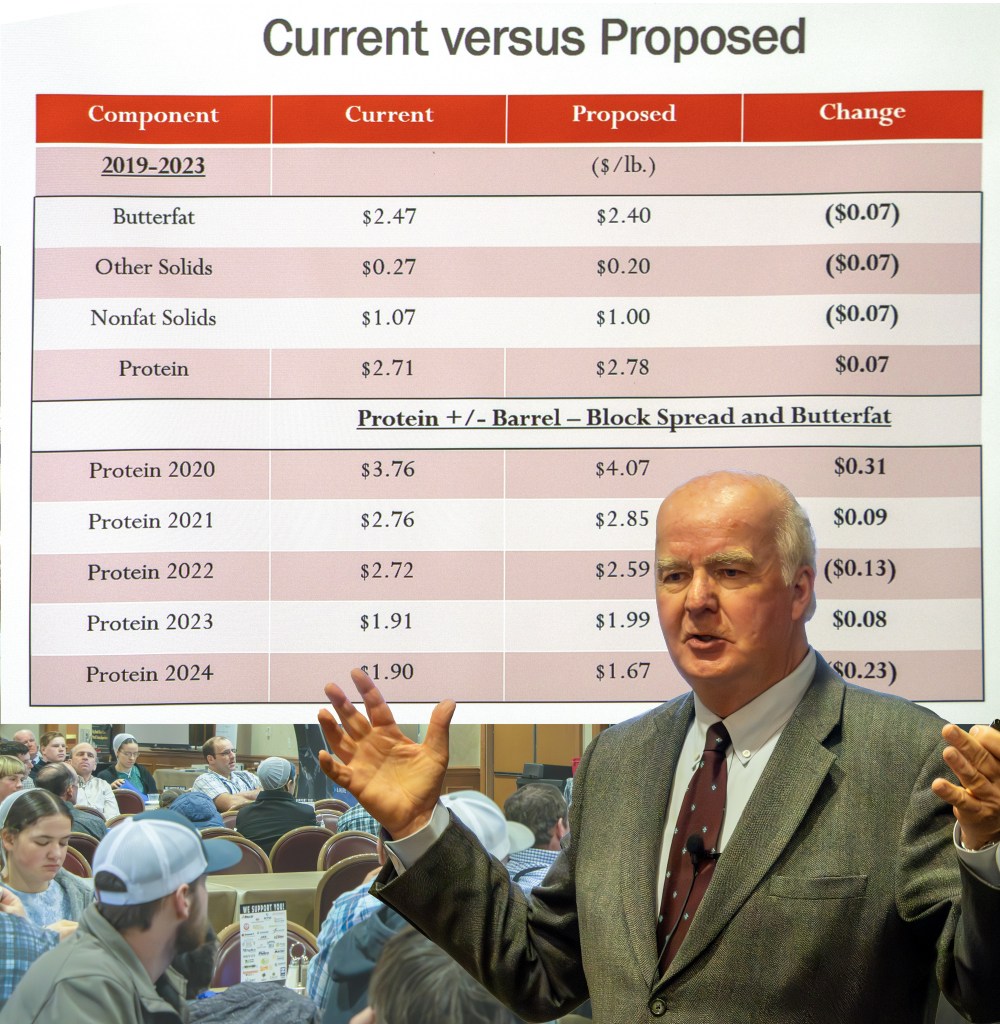

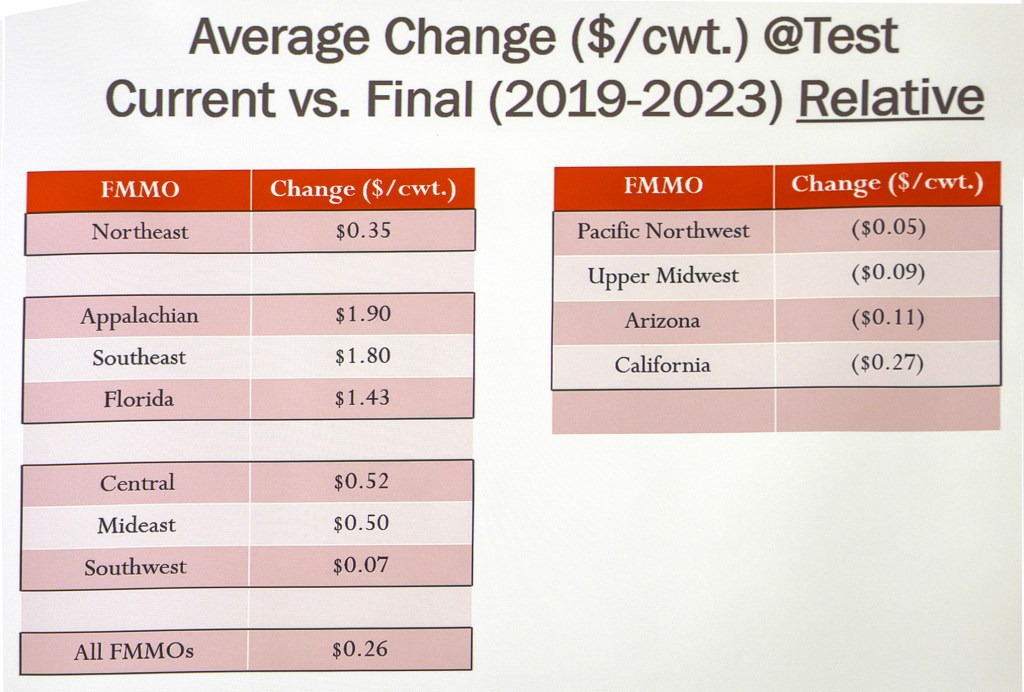

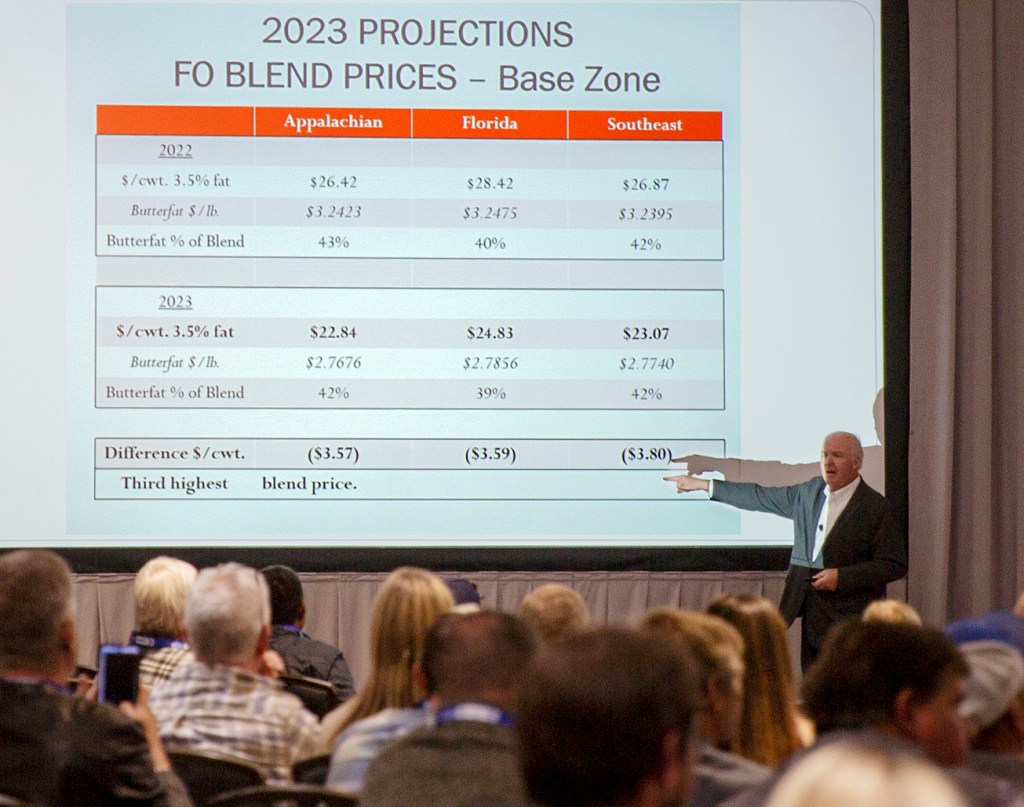

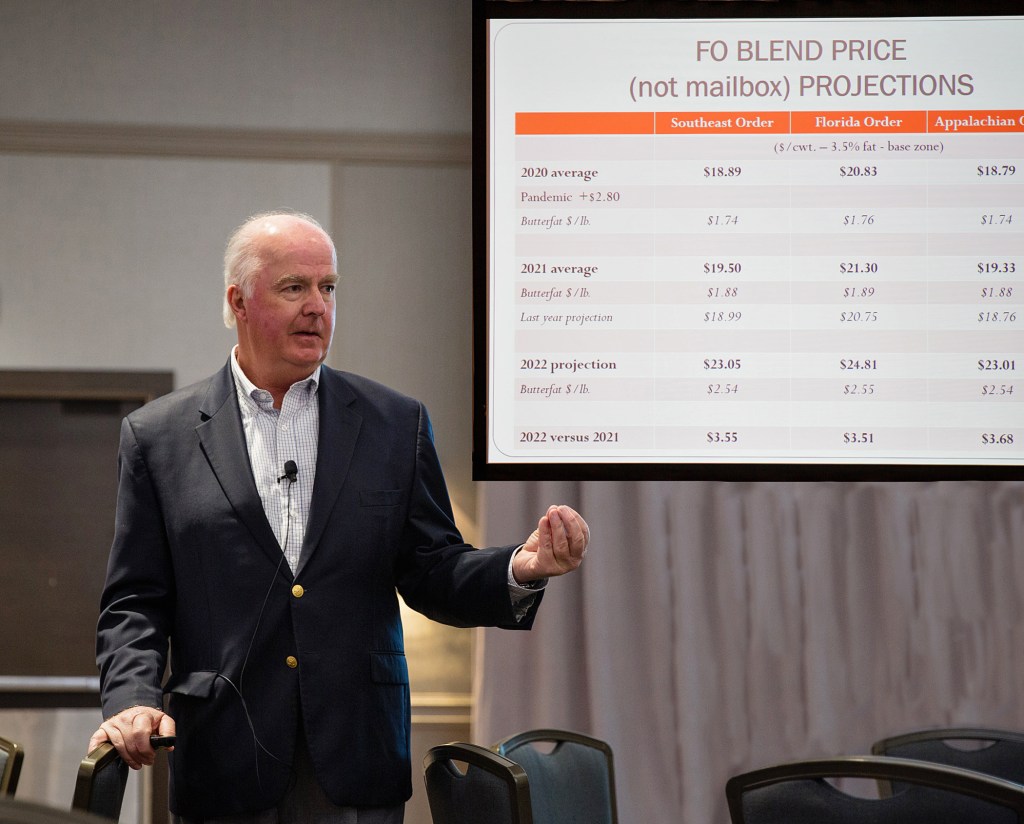

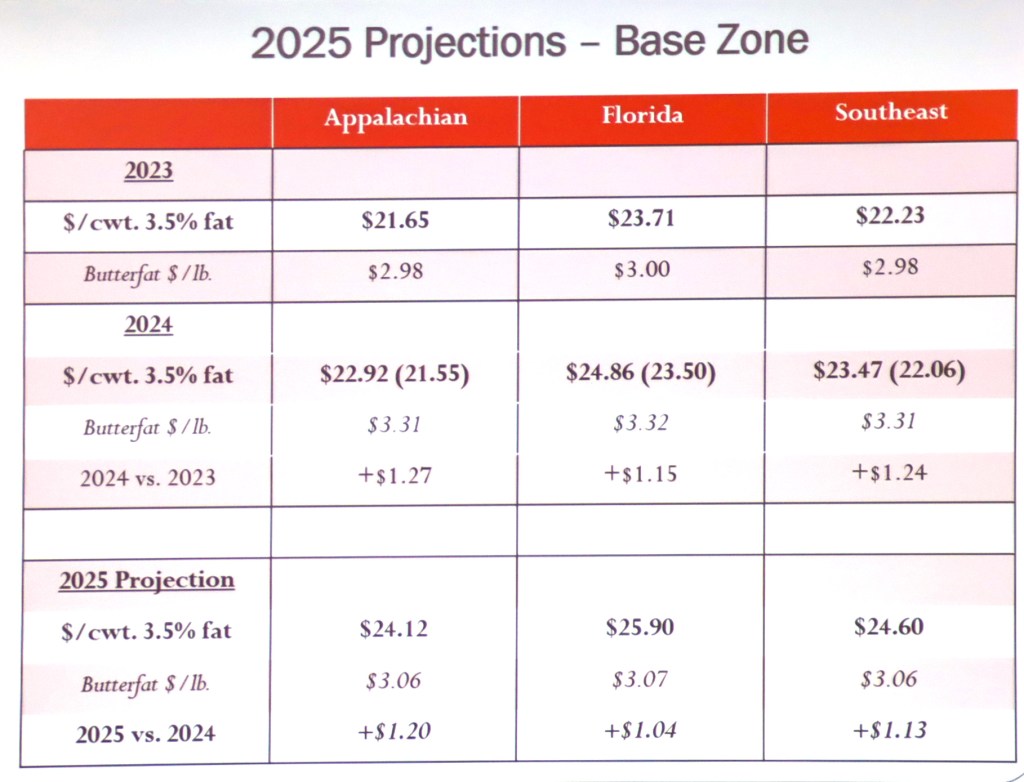

This year, he is projecting prices in the Southeast markets to rise by $1.20 per hundredweight as an average for 2025 vs. 2024 in the Appalachian region ($24.12), $1.40 in Florida ($25.90) and $1.13 in the Southeast Order ($24.60). Most of the increase will come from the skim side this year because the FMMO changes, which will be implemented in the second half of 2025, will pressure butterfat value.

Producers are making higher butterfat milk, averaging well over 4.0% across the three Southeast Orders at 4.06 in Appalachian, 3.92 in Florida, and 4.11 in the Southeast. This compares with 3.65% across the three Orders in 2010.

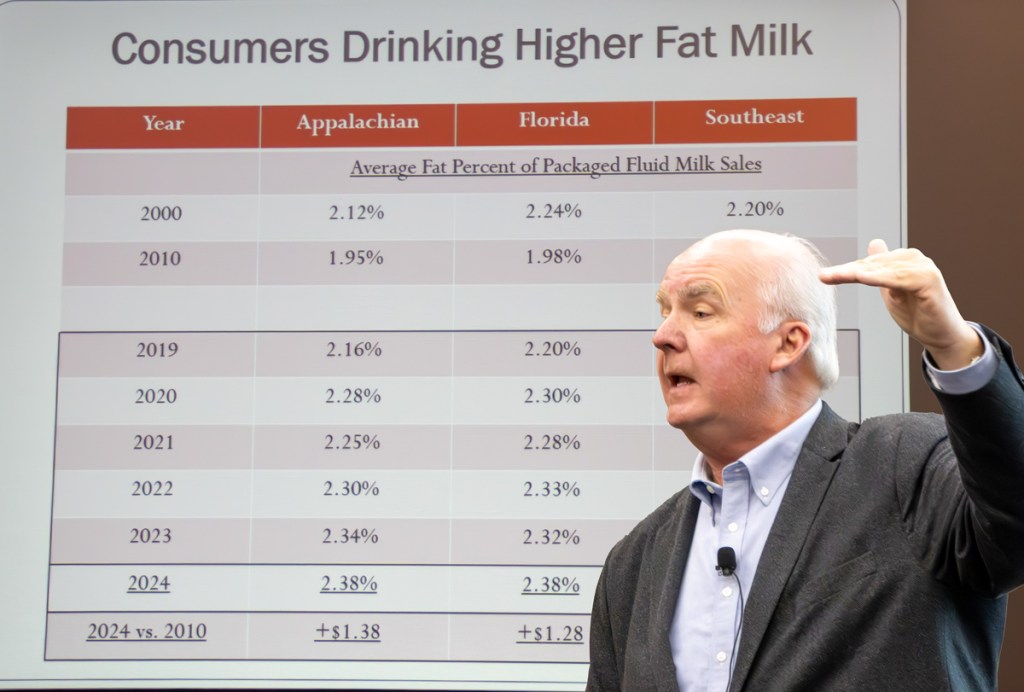

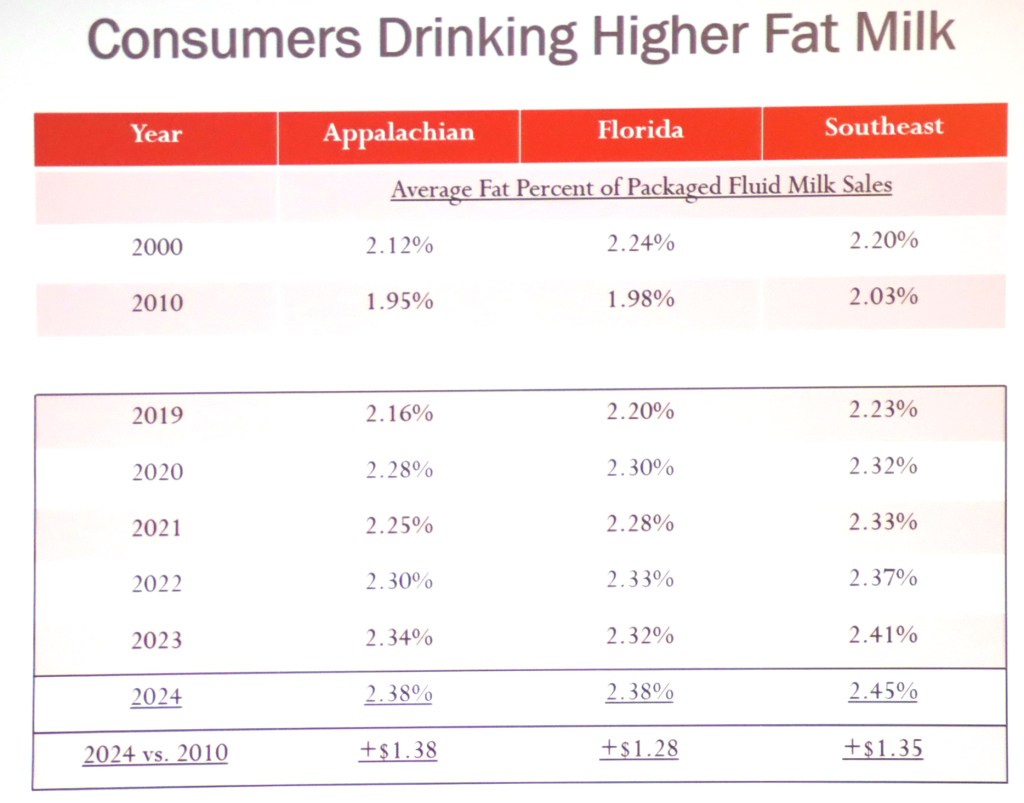

“Additionally, consumers are also drinking higher fat milk,” said Covington, calculating the average fat percentage of Class I sales in the three Southeast Orders rose from 1.95% in 2010 to 2.4% in 2024.

“In 100 pounds of Class I milk in the Appalachian Order, for example, that 2.38% fat made the milk worth more money, $1.38 per cwt more,” he said, with a chart showing Southeast producers saw a $1.28 benefit; Florida $1.35.

“There has been a big change in consumer preference, and that has raised your Class I price,” he said.

He commended dairy producers for improving their components, which has also improved their milk price.

“You’ve done this through genetics and feeding and nutrition programs, and it’s not going to stop. We are moving quickly to Holsteins making milk like Holsteins and testing like Jerseys.”

Other good news heading into 2025 is dairy product inventories are in good shape, he said. Cheese stocks are down, powder is up just a small amount, dry whey inventory is way down and butter inventory is flat.

Dairy product demand is up, but Covington sees a bit of a challenge looking at demand on a total solids basis because “we are exporting more cheese and less powder.”

Looking ahead, he gave attendees a lot to think about on the changing structure and markets in the dairy industry.

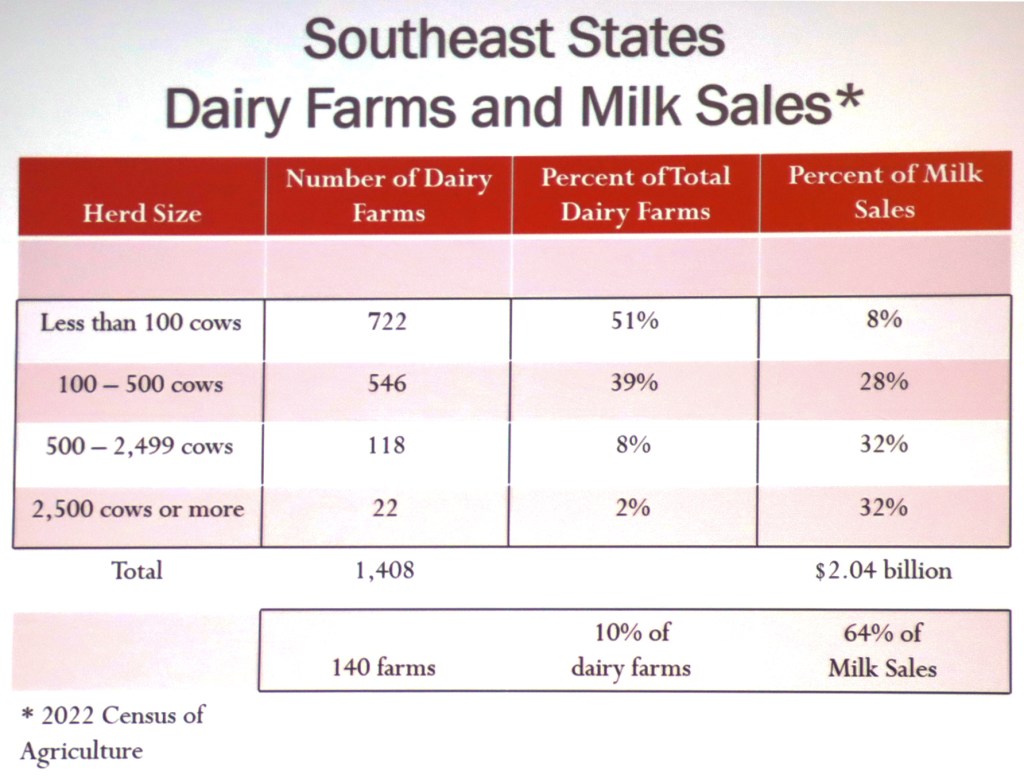

Covington observed that 10% (140) of the 1408 dairy farms that were counted in the 2022 Census of Agriculture in the Southeast had 64% of the region’s milk sales.

Of that 140, there were 22 farms with 2500 cows or more, producing 32% of the region’s milk.

“This is happening all over the country,” said Covington. “We are getting more concentrated.”

This year the milk production advantage flipped back to Florida by slightly more than Georgia, but the two states together have reached 50% of Southeast milk sales. Covington thinks by 2030, “we will see 60% of the milk produced in the Southeast coming from Georgia and Florida.”

When asked what has led to Georgia’s rapid increase in production over the past few years, Covington said “Georgia dairy farmers want to expand and they have the ability to expand. They are progressively making more milk per cow and have the land mass and support.”

His “demand and supply” summary for the Southeast region shows 1160 dairy farms at the end of 2024, producing 8 billion pounds of milk with 32 regulated milk plants. The region had 8.3 billion pounds of Class I fluid milk disposition, and 0.9 billion pounds of Class II products processed.

Against those numbers, the amount of packaged fluid milk products sold in the Southeast was 10 billion pounds. “The Southeast is still a deficit area, and there is room for growth,” he said.

As for total U.S. milk production, Covington doesn’t see it rebounding any time soon. Cow numbers are moving lower and milk per cow is simply not making the year over year gains seen in the past.

“Milk production has been pretty constant for the last three years,” he said. “We have to go way back to see where that has happened before.”

But he also wanted producers to think differently about production, to realize that in making more components, their milk is generating more products. He calculates that today’s hundredweights of milk, nationwide, yield a half pound more cheese. That adds up.

“You as dairy farmers are doing this. By getting your components up, you are also improving sustainability over time. You are making more products from the same volume of milk,” Covington explained.

“Based on average component level changes, if a plant is making one million pounds of cheese a day, they now need 177 loads instead of 185 loads a day for that same output,” he said.

-30-