Dairy producers and organizations are encouraging more to add names by March 12 to letter seeking equal seat at table for producers in regard to milk pricing policy

By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, Friday, March 5, 2021

EAST EARL, Pa. — Dairy producers from across the U.S., along with many state dairy associations and the American Dairy Coalition, have come together to compose a letter to the National Milk Producers Federation (NMPF) and International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA). The letter addresses the impact of massive depooling in relation to large negative PPDs for dairy farmers across the U.S during the last three months in 2019, eight months in 2020, and is estimated to continue through at least the first four to seven months of 2021.

Dairy producers and dairy advocacy trade associations are invited to add their names as signatories to this letter to the presidents of both NMPF and IDFA. Hundreds of producers and dairy trade associations have done so electronically within the first few days.

The deadline to sign is March 12, 2021.

Farmshine has learned that allied industry persons can also sign and mention how they are affiliated — due to the many jobs, economic activity and livelihoods supported by dairy beyond the farmgate having a vested interest in seeing a price formula that is fairer to producers. Those signing who are not producers, but are affiliated with dairy production, will be listed separately as ‘allied industry’ when the letter is officially presented.

Multiple family members involved in a dairy farm operation may individually sign.

Click here or scroll to the end of the article to view the letter and sign electronically through the automated short form.

Or, read the letter as published in Farmshine. Then, email your name, phone number, city, state, and farm name or allied industry affiliation (veterinarian, nutritionist, lender, accountant, feed sales, custom harvester, heifer grower, etc.) to info@americandairycoalitioninc.com or text this information to 920-366-1880.

A photo example of the electronic form appears below.

In the letter, dairy producers ask NMPF and IDFA to work with them to find a solution that can result in a fairer distribution of dairy dollars.

“Dairy farmers all across the U.S. were stunned to see the huge negative PPD deductions on their milk checks,” states the American Dairy Coalition (ADC) in an email about the letter. “We understand the need to better ensure that processors are able to utilize risk management. However, this came at a huge expense to dairy producers and eliminated their ability to utilize the risk management tools like DRP and DMC if they had already purchased them — leaving many producers with no way to shield themselves from significant financial loss.”

The new formula (average Class III and Class IV advance pricing factors + 74 cents), passed by Congress in the 2018 Farm Bill at the request of NMPF and IDFA, is not acceptable, says the ADC.

The goal of the letter to NMPF and IDFA is to ensure that dairy producers have the opportunity to truly be at the table to find workable solutions for milk pricing.

Remember, NMPF and IDFA advocated the change in the Class I base price that is a key part of the problem — without any hearings. NMPF indicates in various press releases that they are working on this and have a plan to “fix it”, but their plan, as indicated so far, falls short according to available economic analysis.

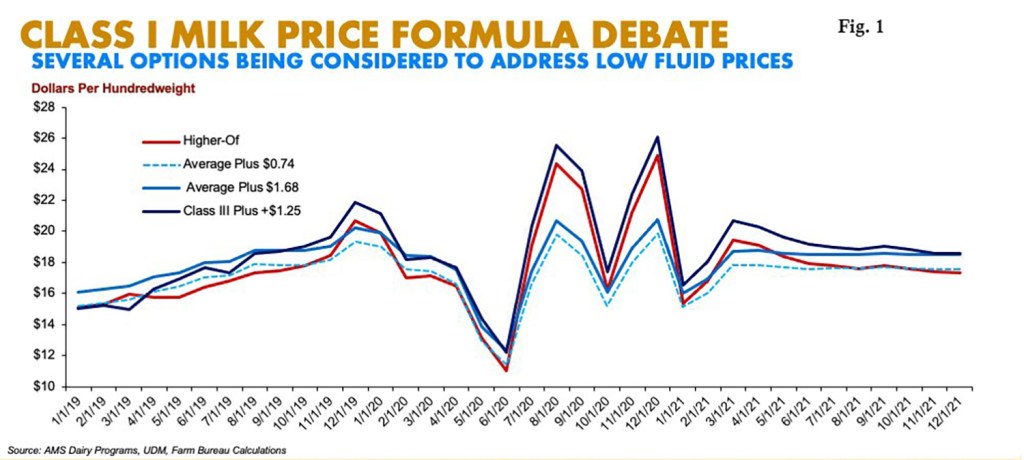

A recent Farm Bureau preliminary analysis of four Class I pricing scenarios (2019-2021), using USDA AMS data, shows this. Fig. 1 (above) compares the previous higher-of, the current average + 74 cents, the current average + $1.68 and Class III + $1.25. Dairy producers are looking to be part of evaluating the best solution using past and future pricing indicators, and it appears that Class III + $1.25 offers a fairer distribution of dairy dollars than the averaging method.

The central point of the letter, however, is to give dairy producers an equal seat at the table. While NMPF represents dairy cooperatives and IDFA represents dairy processors, there is inadequate representation of dairy farmers at the policy-making level on this issue.

The domino effect of the Class I formula change, negative PPDs and depooling, as well as impact on risk management tools, have been hardest on dairy producers in so-called “fringe” areas, and those supplying regional Class I markets. This tends to accelerate the consolidation trend toward ‘cow islands’.

In fact, dairy farm exits in 2020 represent a 7.5% loss in the average number of licensed dairies in the U.S. compared with a more typical attrition rate of 5% annually over the past decade. This, according to USDA’s annual milk production report released last Tuesday (Feb. 23).

Producers interviewed in multiple states recently indicated that while the USDA CFAP payments were helpful, they did not come close to covering losses incurred from negative PPDs and the cost of risk protection tools they chose to purchase but which did not protect against this depooling-negative PPD risk. In many cases, those producers using risk protection through futures markets, actually had additional costs in margin calls that were not recouped in the real milk check when the market went against the hedge.

In short, not only are milk checks not transferring equitable value, the risk management tools offered by USDA and privately, do not work as intended or expected.

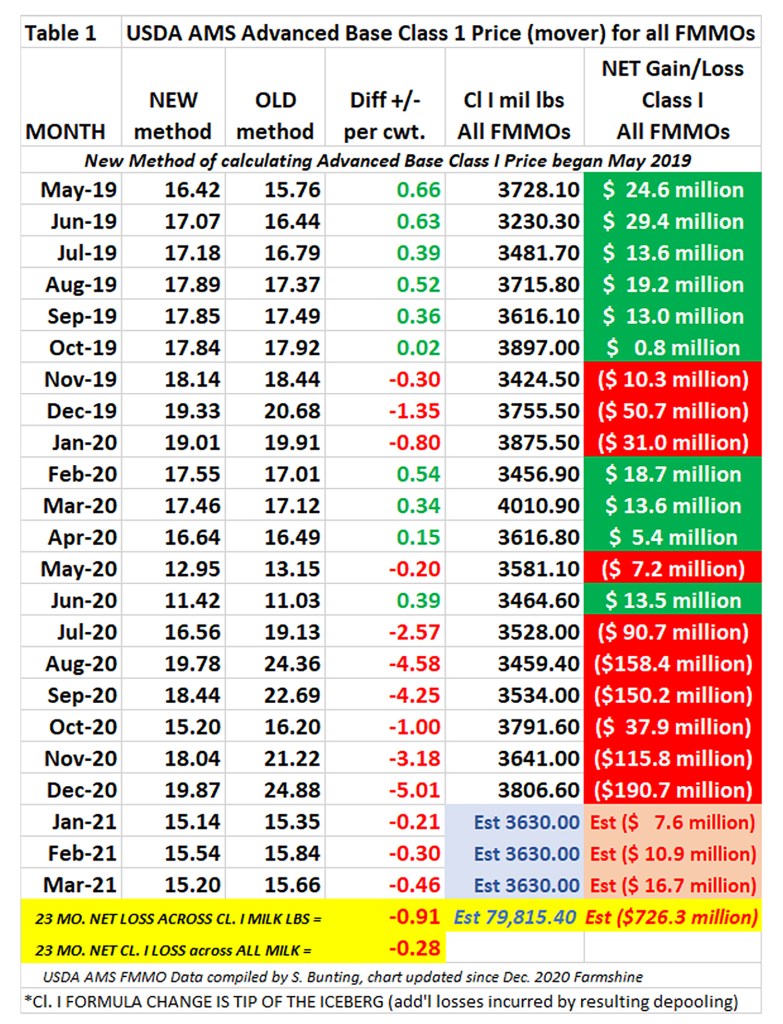

Across all 11 FMMOs, the NET loss on Class I milk pounds, alone, due to the new Class I formula, amount to over $726 million. (Table 1). This translates to a 91-cent per hundredweight NET loss over 23 months (May 2019 through March 2021) on Class I utilized milk and a 28-cent per hundredweight NET loss over 23 months on all milk pooled across 11 FMMOs.

Normand St-Pierre, Ph.D., PAS, shows the losses in his 20-month chart May 2019 through December 2020. As director of research and technical services for Perdue Agribusiness, he broke down the amounts for each FMMO in his “Tiny change with unforeseen consequences” Perdue weekly dairy outlook recently.

“Cumulatively, since the new formula was implemented (May 2019), producers have suffered a (20-month net) loss of $714 million. If from here on the new formula would always produce a gain equal to the average gains that have occurred in the 10 winning months since May 2019 (i.e.,~ $0.40/cwt), it would take producers 50 months to recover the $714 million in lost income.”

In fact, with current futures markets projecting a continued divergence of Class III and IV advance pricing factors by more than the ‘magic’ $1.48 per hundredweight, this situation of negative PPDs, depooling and milk check value extraction will continue for at least another four months, digging the milk check hole even deeper for dairy producers.

Producers are often told that negative PPDs are ‘good’ because it means milk prices are going up. This used to be the case back when the ‘advanced pricing’ aspect of the Class I formula was the main reason for small negative PPDs occurring once in a while.

The situation today is far different – largely due to the change in the Class I base price from ‘higher of’ to averaging Class III and IV pricing factors. The net losses over the past 23 months will not be ‘caught up’, and as St-Pierre points out, the situation is now at the point that it could take years to catch up or recoup even with a tweak.

St-Pierre also observed that producers in the Northeast FMMO suffered losses from the formula change that were the largest in total across all FMMOs, but nearly equal to the average loss per hundredweight across all FMMOs. The losses per hundredweight are largest in Florida’s high Class I milk marketing order, of course.

Now consider that the Class I shortfalls created by the lopsided Class III vs. Class I relationship prompted massive depooling. As previously reported in multiple Farmshine articles and Market Moos columns, only the milk directly associated with the Class I plants is truly regulated to be pooled. Handlers of Class III milk are accustomed to getting a check from the pool, not writing one to the pool.

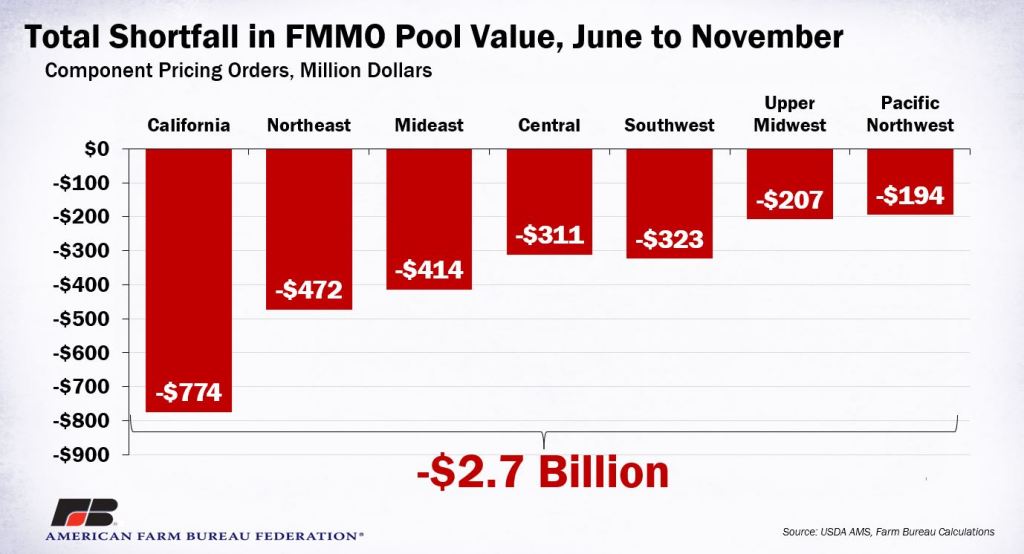

This Class III over I situation creates collective shortfalls in Federal Milk Marketing Order producer settlement funds when massive depooling occurs. This has resulted in a collective net loss of well over $3 billion ($2.7 billion as of the end of November), as represented by negative PPDs across the 7 multiple component-priced FMMOs and the aforementioned Class I skim losses in the 4 fat/skim-priced FMMOs.

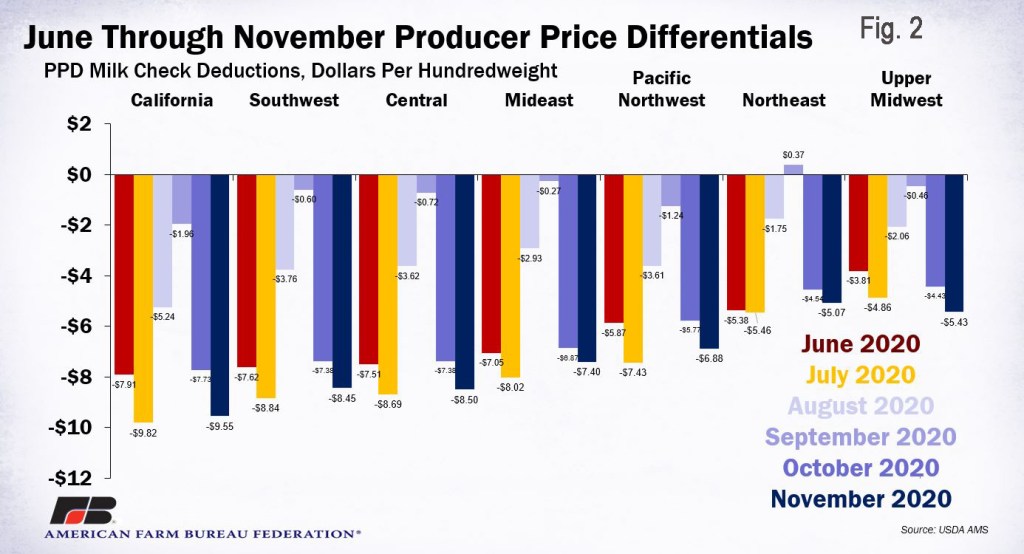

Fig. 2 and 4, from American Farm Bureau based on USDA AMS data, shows the depooling / negative PPD losses just for June through November 2020, but the losses continue in the months since then for which data are available, and the futures markets suggest this will continue into at least July 2021.

USDA AMS answered Farmshine’s question last year about these losses in relation to calculating the “All-Milk” price on which Dairy Margin Coverage is based. Their response indicated that some of this depooling / negative PPD loss is included as value in the All-Milk price. It is seen as value received by producers because the dollars are “in the marketplace” due to the FMMO end-product pricing formulas – even if these dollars are not passed on to producers after producer settlement funds are depleted by depooling.

Farm Bureau chief economist John Newton wrote in his December 2020 Market Intel analysis of the negative PPD impact June through November 2020: “To put this into a farm-level perspective, assuming a national average milk yield per cow of nearly 12,000 pounds of milk produced from June to November, a 200-cow dairy in western Pennsylvania would have experienced PPD milk check “deductions” of nearly $130,000. Similarly, for a 3,000-cow dairy operation in California, the negative PPDs would represent milk check deductions of more than $2.5 million.”

Newton goes on to explain in the article published in the December 25, 2020 edition of Farmshine: “What makes the situation even worse is public and private risk management tools such as Chicago Mercantile Exchange futures contracts, Dairy Margin Coverage and Dairy Revenue Protection were unable to protect against PPD price risk. Margin calls on Class III milk likely made the negative PPDs sting even more as milk prices rapidly rose.”

So back to what dairy producers can do! Read the letter and consider signing it. Share it with others. Talk to your local, state and regional dairy organizations and farm organizations. Ask them to sign as organizations. Both individuals and organizations can sign on.

The bottom line is that dairy producers need an equitable seat at the table where decisions are made that affect how dairy value is shared. NMPF and IDFA — as processors — wear multiple hats and do not wholly represent the on-farm producer interests.

To view the letter (below) click here and look for instructions to electronically add your name, or the name of your organization. Or read the letter below and click here for the direct link to electronically add your name — or the name of your organization — to the letter.