USDA Standoff?

DTN policy editor Chris Clayton is reporting that a standoff could be brewing at the USDA between current Ag Secretary Tom Vilsack and the Trump transition team. Vilsack has urged the Trump team to sign “key ethics documents required by the Presidential Transition Act as soon as possible” so they can start the process of “educating folks… about what they are walking into,” and so the next Secretary of Agriculture “can be fully prepared for the job she is undertaking.”

After 12 years at the helm of USDA, with a 4-year intermission between the Obama and Biden Administrations, pulling a cool million in dairy checkoff salary, Sec. Vilsack has watered down dairy in the WIC program, mangled the recently completed Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee selection and recommendation process, further deflated whole milk and dairy’s position in the school lunch and other nutrition programs, and has been tightly tied to his pet projects, especially the climate-smart partnerships he lobbied the Senate for in 2019 while working for DMI, given the ‘slush fund’ appropriated through the so-called Inflation Reduction Act that many describe as the undercover Green New Deal.

For that initiative, alone, Vilsack told the House Ag Committee a year ago he was hiring 4000 new USDA employees and that 4000 more would be needed at local levels to gather data, do the monitoring, and herd farmers into the data-collection squeeze chute to participate in climate-smart projects. The House Ag Committee expressed their concern about funds getting to actual farmers. (See Feb. 16, 2024 Milk Market Moos ‘carrot and stick’)

Hog wrestling strategy?

One could say there are a lot of pigs at the USDA climate trough. The whole deal needs a good auditing to see how much of what was spent or promised is getting into the hands of actual farmers and their on-farm contractors vs. going into the black hole of bureaucracy.\

While Trump’s Ag Secretary-Designate Brooke Rollins, still to be confirmed by the Senate, is only the second woman nominated to head the USDA, don’t let her femininity fool you. One thing we learned watching Rollins, 52, as a guest on legendary football coach Lou Holtz’s Nov. 4th Show about faith and leadership, this Texas Aggie was a hog wrestling champion.

Holtz asked Rollins about the hog wrestling title. It was 10 years ago when she and her sister Ann went to Bandera, Texas for an annual festival. They decided that year to enter the annual Wild Hog Explosion Contest. They won, even set a record, against younger women in the competition.

Rollins recalled: “We had a strategy and a plan, which seems to be a common theme in my life. You always have to have a strategy, and you always have to have a plan. We had a plan to wrestle that wild hog — and he was a wild, big hog — and put him into a bag and drag him across the finish line.”

A mom-coach could do wonders

USDA Secretary nominee Rollins also revealed that while coaching her daughter’s softball team a few years back when she was 10, they wrote their own mission statement that hung on the fence for every game. “Coaching is a reflection of life, to be our best, work as a team, have a common goal, never give up, and go for the win, every time.”

Rollins and Holtz talked of her leadership style to “find amazing people” to build teams that work together “not caring who gets the credit, but what gets accomplished.”

When asked the Bible verse most meaningful in her life, she said for this season in time “with the arrows slinging every which way,” Joshua 1:9 “Be strong and courageous. Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged, for the Lord your God will be with you wherever you go.”

One that strikes a chord throughout her life is: Matthew 25:40: “Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.”

When it comes to USDA’s failed nutrition policy, this verse rings true. It’s also worth noting that Rollins is a mother. That may be just what USDA needs at the top! Mom’s understand the school meal and school milk issue! Can we imagine how many more hungry children could be nourished if USDA devoted funds to the food that are now going to the bureaucrats calculating fat percentages and other criteria to regulate schools so they don’t violate the fat limits; and how much better off those children most reliant on school meals would be if they could choose nutrient-dense delicious whole milk, 3.25% healthy fat.

What’s up with milk production?

USDA Dairy Market News reports that milk availability is still tight for processors. Some processors expect milk availability to loosen in coming weeks, as plants slow production or shut down during the week of Thanksgiving. Class I bottling is strong as demand from schools is steady up to the coming holiday, and consumer demand increases. Demand from Class III is strong. Cheesemakers report that some plants are running as much as possible. Component levels are reported to be strong across the board. We’ll did into the report next week.

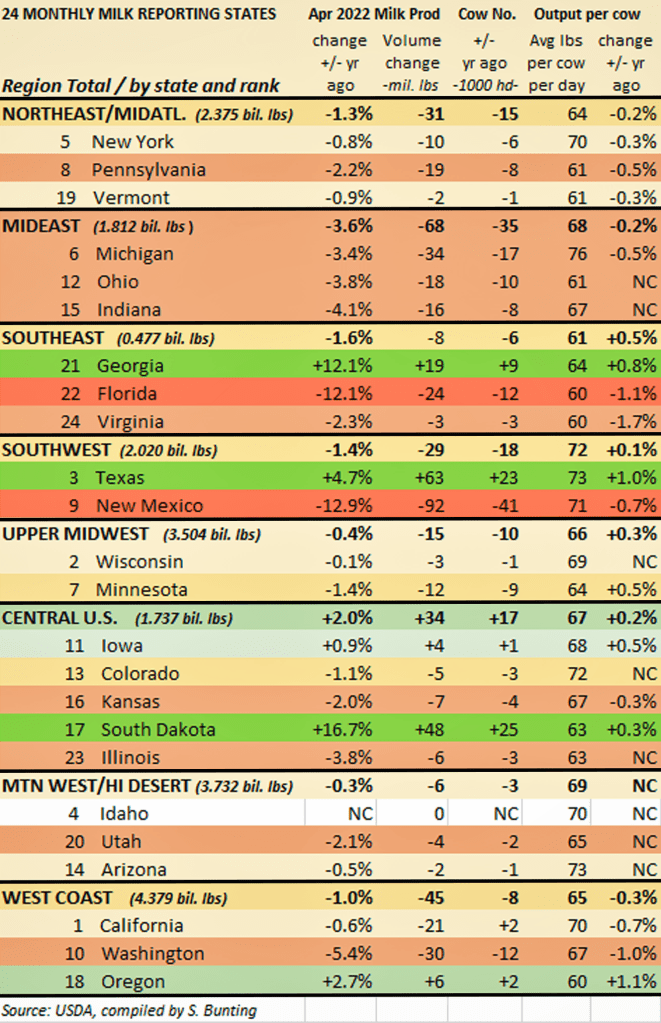

The USDA NASS milk production report released late Wednesday showed total U.S. milk production was up 0.2% in October vs. year ago. Meanwhile, milk production in the 24 major milk producing states gained 0.4% over year ago. For Q3, USDA reports total U.S. milk producers virtually flat with a year ago.

This indicates that states and regions that are expanding milk production rapidly in the Plains from western Minnesota, Iowa, South Dakota south to Texas, have large expansion units coming online — and their own circular systems for heifer-rearing are geared up to fill new stalls to supply new cheese processing that is coming online — perhaps not at all impacted by the overall tight supplies of milk cows, springing heifers, and bred heifers in today’s marketplace.

Remember, the current Secretary of Agriculture, Tom Vilsack, canceled the July 2024 mid-year All Cattle and Calf Inventory, so the industry won’t get a look at dairy and beef numbers until the end of January 2025.

In the East and Mideast, October’s milk production was generally steady vs. year ago. USDA estimates for Northeast and Midatlantic: Pennsylvania up 0.6%, New York up 0.2%, Vermont and Virginia down 0.5%; In the Southeast, Florida down 0.6% and Georgia up 1.9%; In the Mideast: Michigan up 0.5%, Indiana up 0.3% and Ohio down 0.2%.

Midwestern milk production slipped 0.2% and 0.5% in Wisconsin and Minnesota, but grew across the Central Plains, up 3.3% in Iowa, up 4.2% in Kansas, up 9.6% in South Dakota.

Southwest milk production grew a substantial 8.8% vs. year ago in the No. 3 milk producing state of Texas, while New Mexico continued its decline, off 4.4%.

California is in the midst of an escalation in bird flu with production down 3.3% vs. year ago. USDA APHIS reports 261 herds have had the virus in the past 30 days in California, 436 since the first outbreak there in September.

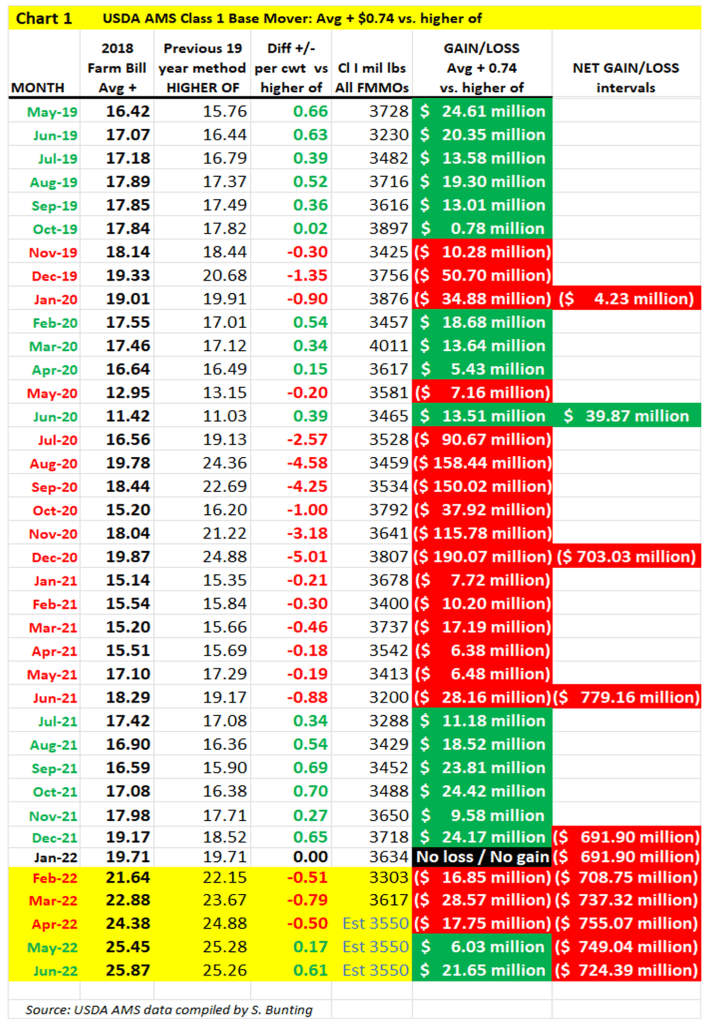

Dec. Class I mover drops $0.90 at $21.43

The December advance Class I base price mover was announced at $21.43 on Wed., Nov. 20 for a loss of 90 cents per hundredweight below November’s Class I mover, but up $1.67 per cwt. above a year ago.The USDA NASS milk production report showed total U.S. milk production was up 0.2% in October vs. year ago. Meanwhile, milk production in the 24 major states gained 0.4% over year ago. For Q3, USDA estimates total U.S. milk production virtually flat vs. year ago.

Class III milk slips lower despite less cheese

Despite USDA again reporting cheese stocks smaller than a year ago for the 8th straight month, dwindling to levels 8% below year ago, the CME spot cheese price headed south this week, dragging Class III milk futures lower too. On Tues., Nov. 26, Class III milk future averaged $18.77 for the next 12 months (Nov24-Oct25), losing 29 cents/cwt — more than was gained last week. Class IV milk futures were mixed, but the 12-month average fell a dime to $20.85.

CME dairy lower, but whey skyrockets

Dairy product prices on the CME daily spot market lost ground across the board this week, except dry whey gained an unprecedented nickel per pound, reaching just shy of what would be a near record 70 cents per pound.

On Tues., Nov. 26, the ‘market clearing’ dry whey price on the spot CME was a whopping 69 cents/lb with 6 loads trading over the 4 days pre-holiday. That’s more than a dime per pound higher than the weekly USDA National Dairy Product Sales Report price that has lagged all year and is the one used in the Federal Milk Marketing Order pricing formulas. Whey is usually the commodity to watch in relation to future milk prices, but it’s not translating. The 40-lb block cheddar price was pegged 4 cents lower at $1.6950/lb with just 2 loads trading over 4 days. Pegged at $1.64/lb, the 500-lb barrel cheese price lost 9 cents per pound with 8 loads trading across the 4 days.

On the Class IV side, the spot butter price fell 11 cents per pound, pegged at $2.4850/lb with 18 loads trading. Nonfat dry milk lost the penny gained last week, pegged at $1.39/lb with 21 loads trading in 4 days.

Live cattle imports from Mexico ‘paused’

USDA APHIS will halt cattle imports from Mexico due to a detection of New World screwworm (NWS) in Mexico Nov. 22. It was discovered in a cow at an inspection checkpoint close to Mexico’s border with Guatemala. USDA reports that around 5% of feeder cattle placements come from south of the border, meaning this pause in live cattle imports will further tighten beef supplies. The USDA cold storage report indicates red meat supplies continue to run below year ago levels.

Dairy Exports: Jekyll and Hyde

Dairy Exports: Jekyll and Hyde No matter where you are on the scale of good, bad or indifferent, exports are essential for agriculture and for dairy.

No matter where you are on the scale of good, bad or indifferent, exports are essential for agriculture and for dairy.