Editorial Analysis: Tumultuous 2024 spills over into 2025 – Part Two

By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, January 17, 2025

EAST EARL, Pa. – Year 2024 was tumultuous, and 2025 is shaping up to be equally, if not more so. Here’s a look at how supply, demand, and other market factors are shaping up for milk prices and dairy margins heading into 2025. This is part two of a four part series, see part one here and part three here.

We are a few weeks away from a few key yearend reports that will give us a better handle on production and cattle inventories, but the current market fundamentals favor a forecast for higher milk prices into 2025.

Better prices

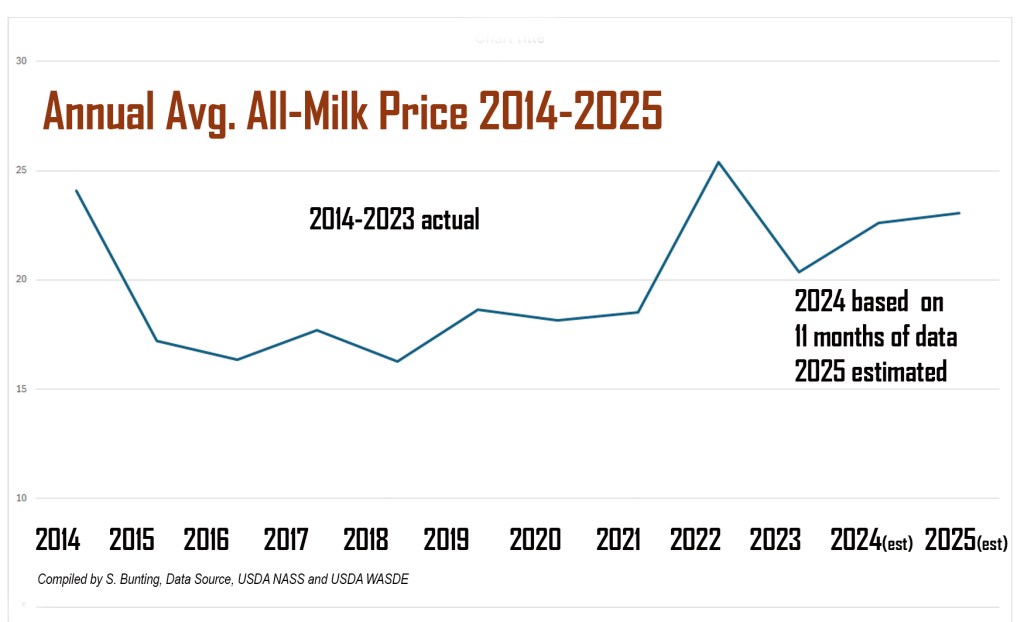

In fact, the Jan. 10th World Agriculture Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) just raised by 50 cents per cwt the estimated 2025 All-Milk price average at $23.05 after having lowered it the month before.

Based on 11 months of official data, however, the January WASDE shaved another nickel off the 2024 average All-Milk price, now estimated at $22.60, which would be $2.20 higher than the average All-Milk price of $20.40 for 2023 but $2.80 lower than the decade’s high point of $25.40 in 2022.

At an estimated $22.60, the average All-Milk price for 2024 would be the fourth time in the past decade and the third consecutive year that the annual average All-Milk price was above the $20 mark. (Fig. 1).

Strong demand

Positive supply and demand fundamentals for 2025 include the reported strong domestic and international demand for cheese and butter; tighter than expected milk supplies; tight to adequate dairy product inventories; growth in year over year (YOY) sales of fluid milk; and strong domestic demand for skim solids in the form of nonfat dry milk, dry whey and whey protein concentrate coupled with reduced production of these products limiting the availability for export.

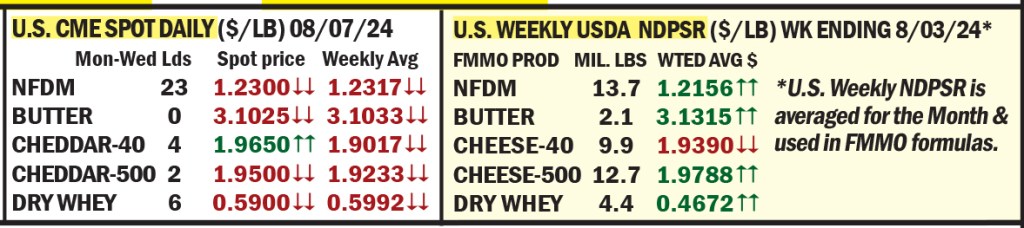

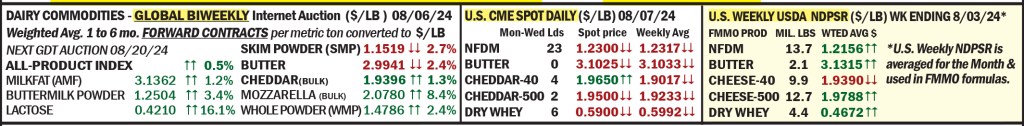

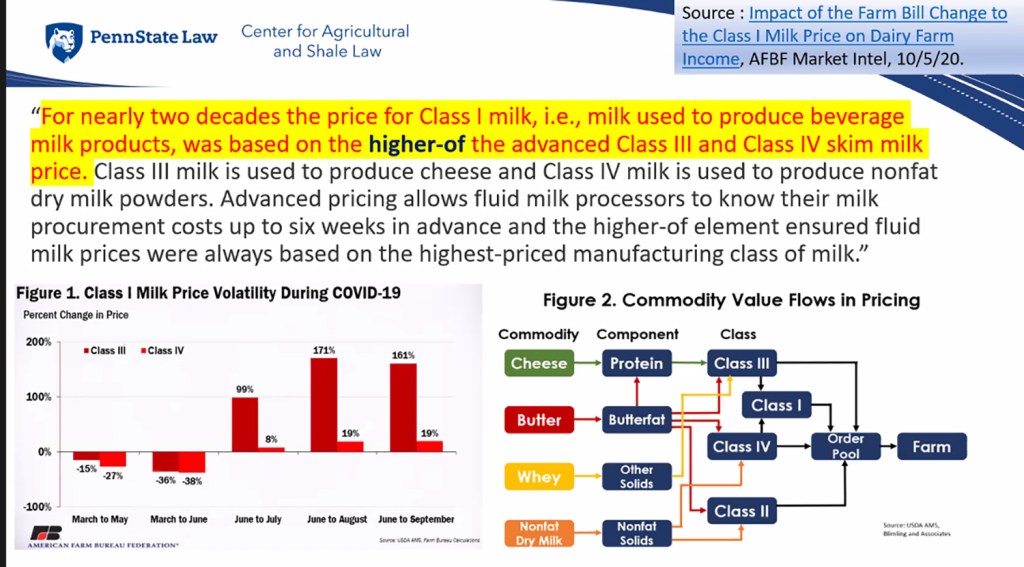

A sustained price rally in the CME spot market-clearing price for the market indicator product dry whey reached a multi-year high of 75 cents per pound by the end of the 2024 and is holding at near 74 cents per pound into mid-January. Trouble is, this market-clearing price has been tardy all year in translating to sales reported on the USDA weekly price survey used in the Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) price formulas.

Despite the positive supply and demand fundamentals, we saw fourth quarter 2024 milk prices decline $1 to $1.50 from the year’s high point at $25.50 in September, and even though dairy products are holding steady on the CME spot cash markets, the CME milk futures markets took a tumble into below-$20 territory across the board this third week of the New Year.

So what’s the deal? Uncertainty.

Fewer cattle?

Uncertainty prevails about future cattle inventories after Sec. Vilsack canceled the mid-year 2024 Cattle Report last summer. The Jan. 1 Cattle Inventory Report comes out Jan. 31st. It’s unlikely to show any big surprises in the two-year trend toward reduced cattle numbers, including dairy replacement heifers. USDA says this report will give the trade an indication of producers retaining dairy heifers for their milk herds.

With prices skyrocketing $800 to $1200 per head above year ago levels for fresh cows and springing, bred, and open heifers, a sudden rise in replacement heifer numbers is unlikely.

Meanwhile, beef-on-dairy calves continue to give dairies an immediate $800 to $1000 check on a 3-day-old bull calf requiring very little input cost. That’s $900 in income per cow for dropping a calf, even before she starts her lactation.

The tug-of-war on breeding decisions for future dairy farm calf crops continues as the total U.S. beef and dairy calf crop, by the way, has already declined 1.6 million head in the two year period from Jan. 1, 2022 to Jan. 1, 2024. On Jan. 31st, we’ll see what the Jan. 1, 2025 numbers say.

Global trade

Uncertainty also exists around global trade amid ‘tariff talk’ against the backdrop of YOY growth in export volume, that is tempered by YOY growth in import volume. The January WASDE expects the trend of export volume growth to continue, but also expects the larger import volumes to continue. While the report specifically mentions cheese and butter, USDA FAS data show growth in the imported volume of skim milk powder, and especially YOY growth in whole milk powder (WMP) imports in each of the past four years.

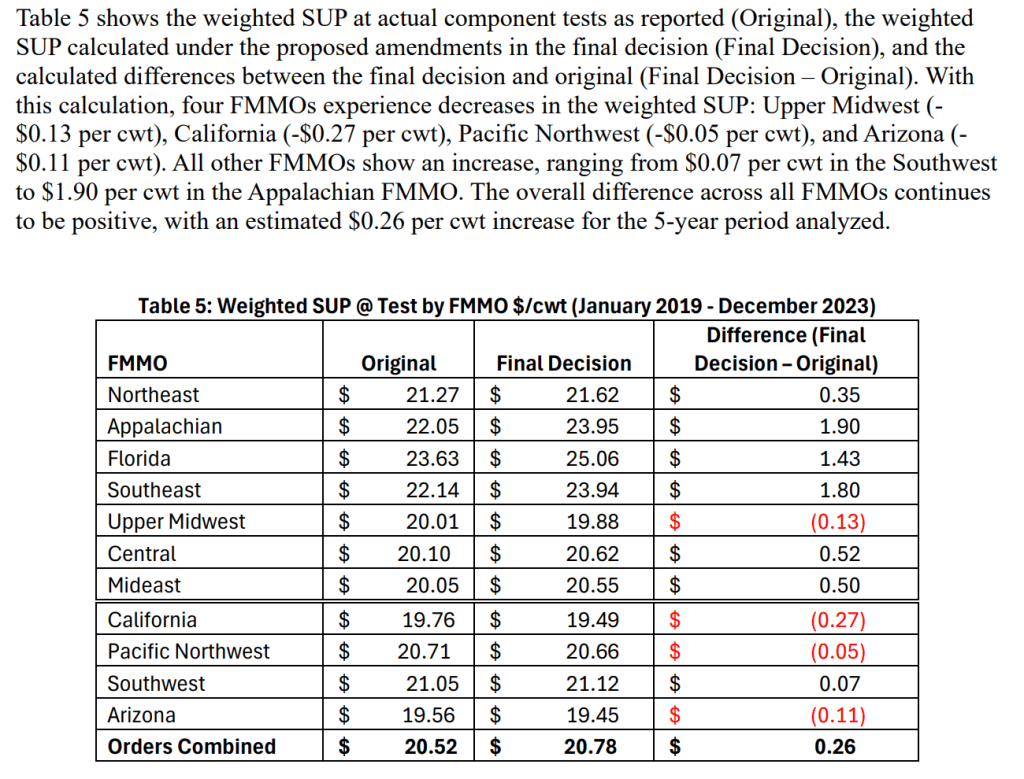

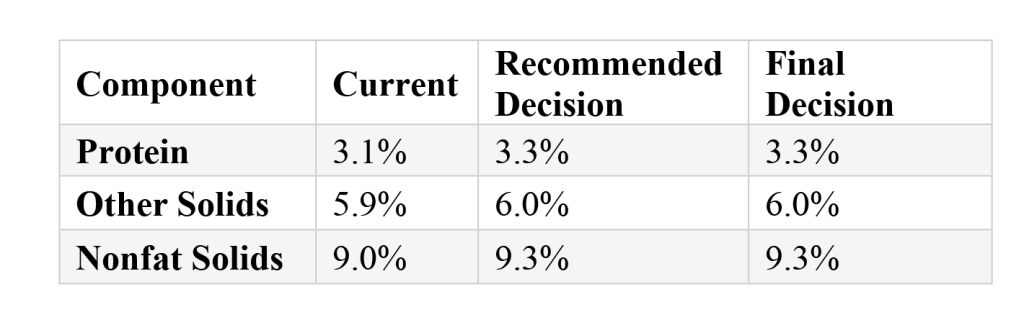

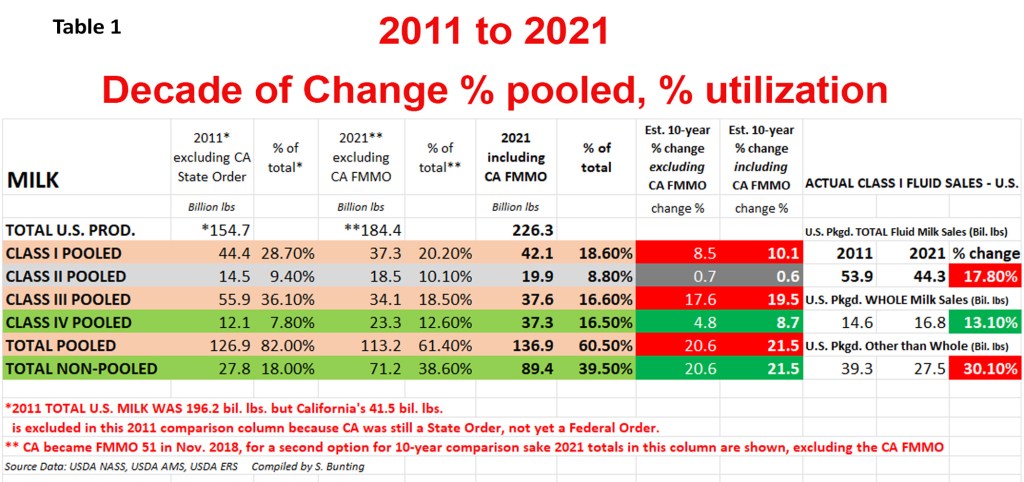

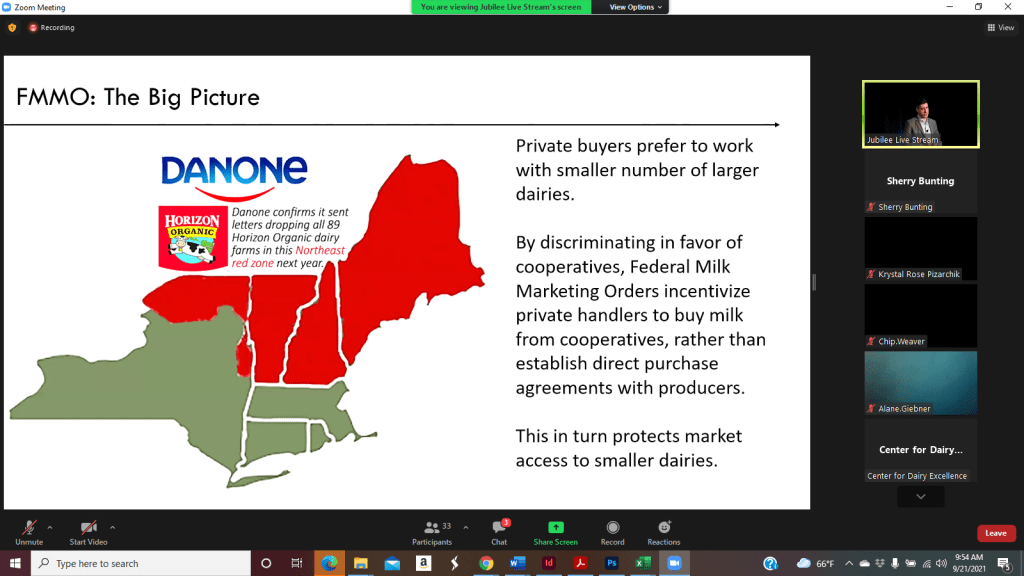

FMMO changes

Uncertainty about the implementation of USDA Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) price formula changes in the second half of 2025 that will impact risk management. The updated make allowances will trim class and component index prices by 75 cents to $1.00 against a CME milk futures markets that bases contracts on the FMMO formulas. That changeover will have to be dealt with.

Uncertainty about how new, efficient expansions of cheese and ingredient production capacity may be tied into sourcing from multi-site dairy farms that have planned expansions with internal heifer replacement models. What will be the impact on the rest of the industry when they start cranking out tons more cheese on the new and higher make allowance margin.

H5N1 impacts

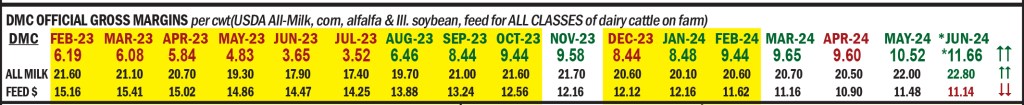

Uncertainty about milk production trends after the impact of the bird flu outbreak in California dragged down total U.S. milk output well below expectations. The next report for December milk output will be released on Jan. 24th.

The January WASDE reduced its total milk production forecasts for 2024 and 2025, driven by “lower milk cow inventories and lower expected milk output per cow.”

This came on the heels of the November milk production report released in late December, showing California’s 9.3% drop in state-wide milk output, attributed to HPAI H5N1 hitting at that point half of the state’s dairy herds. This drove the total U.S. output down an unexpected 1% YOY.

The WASDE also forecasts “slower growth in output per cow” in its rationale for reducing the milk production estimate for 2025. This means what producers have been reporting is now showing up in the USDA data. Producers in areas hit by H5N1, especially California, report an initial 30 to 40% herd level production loss that only comes back about half-way, six to eight weeks later.

Producers also indicate a 2% increase in herd-level mortality and increased culling. Both veterinarians and producers in previously affected areas are now reporting impacts on dry cows and springing heifers, aborted calves, shaved production peaks, and emerging questions about milking performance in the following lactation.

According to APHIS data, as of Jan. 10, the virus was detected in 708 dairy herds in California since the outbreak was first reported there in September. That’s nearly 75% of the state’s dairies affected to-date. In the past 30 days, 66 California herds have been affected, with the most recent detection on Jan. 10.

Apart from the California outbreak, the only other detections of H5N1 on U.S. dairies in the past 30 days is one herd in Michigan on Dec. 30. This is good news, considering that 13 states have now been fully brought into the National Bulk Milk Testing Program announced on December 6th as a mandatory program for all 48 continental states.

Those initial states include California, Colorado, Indiana, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Montana, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and Washington.

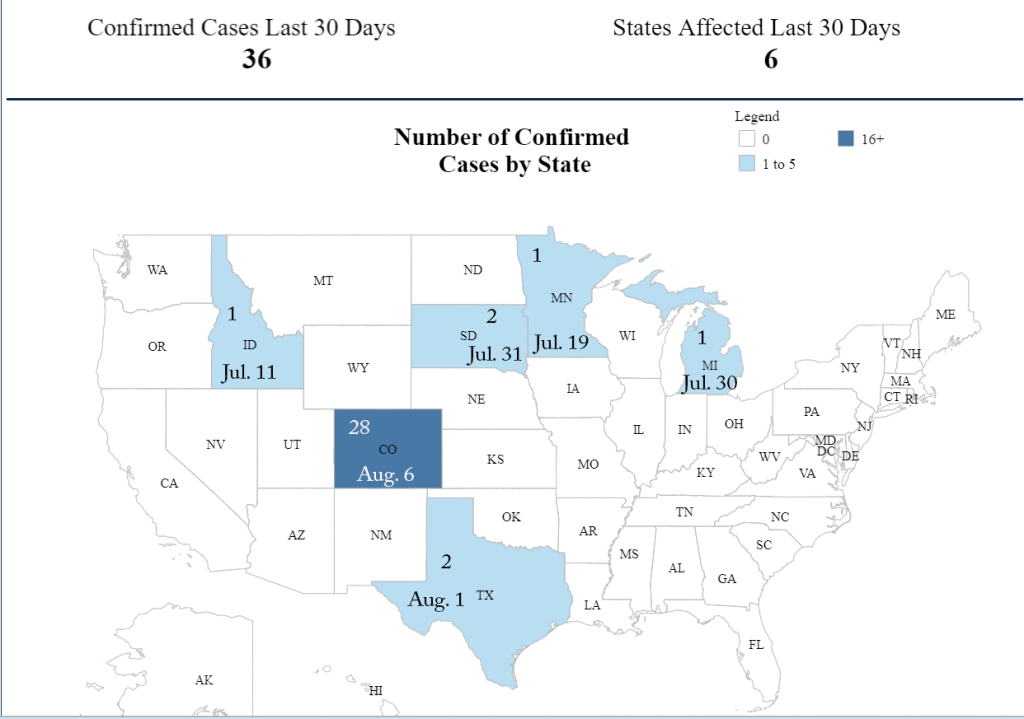

Better margins

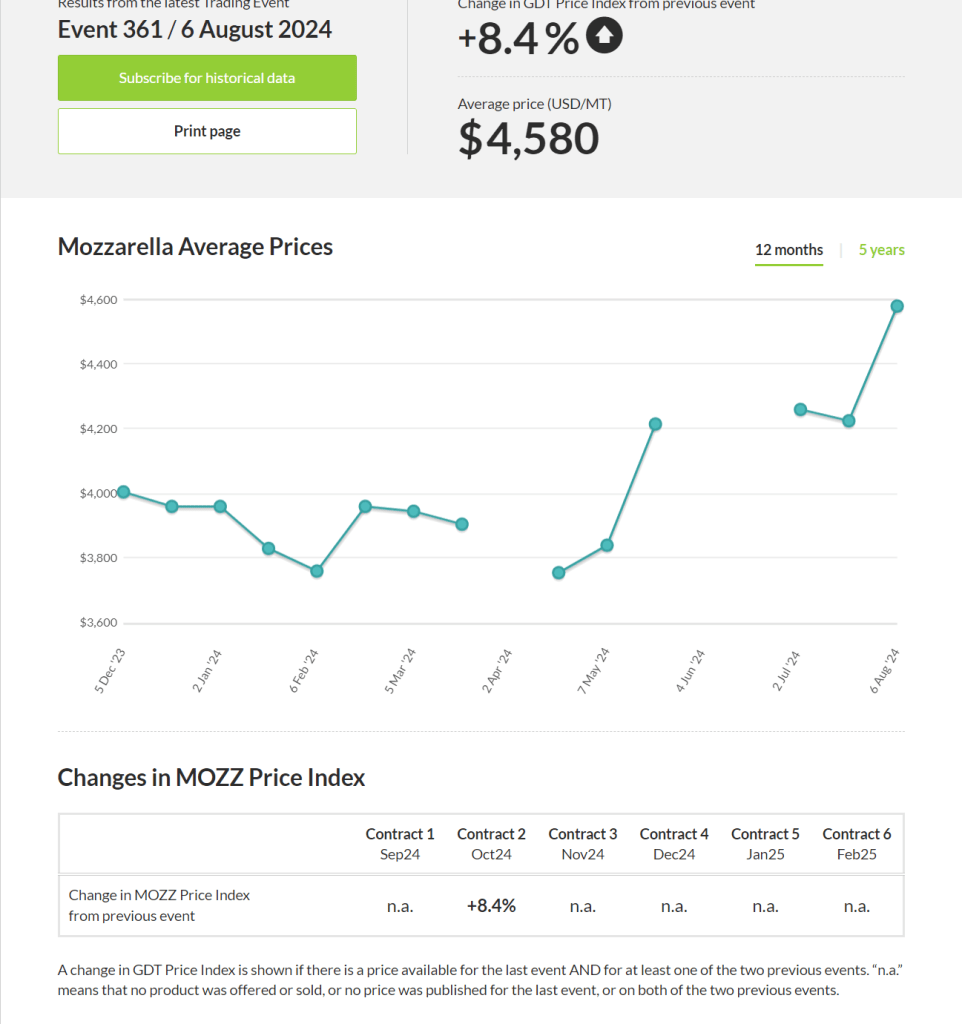

For 2024, the milk over feed cost margin only fell below the Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) program’s highest payment trigger level of $9.50/cwt in the first two months of the year. In fact, Sept. 2024 saw the highest DMC margin on record at $15.57 with an All-Milk price of $25.50 and a feed cost at $9.93. Since then, Q4 margins have declined to $14.50 as the All-Milk price fell and feed cost remained fairly constant.

This measure does not account for the higher fuel and energy costs, higher labor costs, rising cost of insurances, higher interest rates on capital, and generally higher costs for other inputs that keep a dairy farm going.

Labeling games

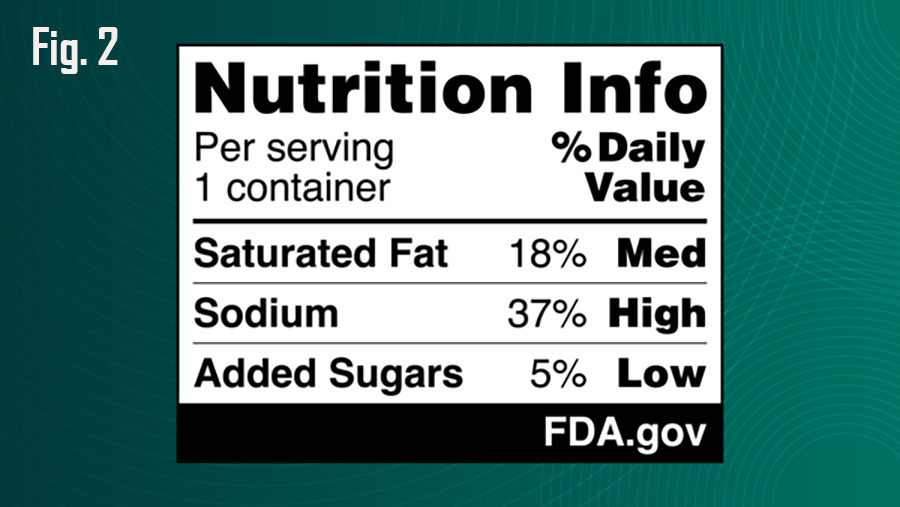

Other market factors may increasingly play a sidebar role. On the demand side, FDA’s new draft rule on Jan. 14 requires front-of-package labeling (Fig. 2 example above), which in addition to listing grams of saturated fat and percent of total recommended daily value, will now use a rating system to mark the saturated fat content of foods and beverages as high, medium, or low as the outgoing Administration attempts to further push consumers into the low-fat Dietary Guidelines regime.

Despite the noise around low-fat and anti-animal, USDA reports strong demand for real beef and dairy, with whole milk the top volume growth category in the fluid milk market.

FDA also issued new draft guidance on Jan. 14 for ‘best practices’ in naming and labeling of fake plant-based foods that are marketed and sold as alternatives for animal-derived foods. This guidance applies to fake meat, eggs, seafood, and dairy products, but does not include the labeling of fake beverage milk. FDA reminded the trade of its 2023 draft rule for plant-based fake milk.

his follows the same pattern as the previous fake milk guidance – recommending that the plant-based food be “qualified by type of plant source” when using the name of a standardized animal product such as cheese or beef. (Fig. 3 above)

This is how FDA has treated fake milk for the past 15 years, by allowing for example, the ‘almond’ qualifier in front of the word ‘milk.’ The FDA’s 2023 guidance on milk, specifically, recommends, but does not require, additional nutrition statements to clarify nutritional differences.

Frankenfoods

Likewise, on the supply side, fake Frankenfood is emerging as FDA continues mulling a draft rule on what to call the products of lab-creation seeking to replace real animal-derived foods.

For dairy, this comes in the form of microbes bioengineered with bovine DNA to excrete fake dairy protein and fat analogs that USDA refers to as “precision fermentation protein products” while lab-created gene-edited cells growing into blobs of fake meat, egg, seafood, even dairy analogs are referred to as “cell-cultured” chicken, seafood, beef, dairy etc.

In late December, the USDA Economic Research Service (ERS) released its first ever report on “The Economics of Cellular Agriculture.” This means the Department has now recognized Frankenfood as part of the Agriculture domain. Yes, we’re talking about fake food from a factory, not a farm.

The 45-page ERS report notes that for 25 years, scientists in the public and private sectors have been “actively researching methods for producing food products that are physically and chemically equivalent to livestock- and poultry-produced foods (i.e., meat, dairy, eggs) but that minimally rely (if at all) on animals.”

By 2023, more than 200 private firms existed worldwide, and cumulative invested capital in the cell-culture and precision fermentation industries exceeded $5 billion. As of 2024, more than 100 patents have been filed. U.S. food agencies (FDA, USDA and FSIS) have been developing regulatory frameworks to accommodate and ensure the safety of these products, according to the report.

To-date cell-cultured fake chicken meat has been commercialized in Singapore and the U.S., largely through unique restaurant chains. This led to states like Florida banning the stuff.

Meanwhile, “precision fermentation-derived fake dairy protein analogs have been commercially available more broadly,” according to the ERS report.

These Frankenfoods tout smaller carbon footprints, less land and water usage, but ERS authors observe that, “Open questions remain concerning the design of bioreactors and important elements of the production process, including cell source, growth medium, and energy requirements, as well as the optimal size and configuration of production-processing plants.”

The report states so-called “precision-fermented dairy products are already on the market in the U.S., and, like their plant-based counterparts, sell for a premium over animal-based. For example, the company Perfect Day partners with other companies that sell products like ice cream and milk featuring their precision fermentation animal-free whey protein.”

In this way the fake dairy protein analogs are marketed as an ingredient in a business-to-business vs. business-to-consumer model.

According to the ERS, precision fermented protein products (fake dairy analogs) are increasingly available in U.S. markets, while cell-cultured products (fake meat and seafood analogs) are not.

Short run profitability, according to ERS, will rely on consumer willingness to pay for these products with current consumer attitudes described as “mixed.” But the labeling guidance remains unclear as the fake dairy protein analogs are actually the harvested excrement of the bioengineered microbes, not the DNA-altered microbes themselves. Consumers need to know what they are buying.

The ERS report also states that despite some of these companies and investors releasing bold lifecycle ecosystem claims, the “environmental impacts are largely unknown.”

Part III in a future Farmshine will look at the yearend reports due later this month.

-30-