By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, Feb. 23, 2024

EAST EARL, Pa. — The status of the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act, S. 1957, has 17 Senate sponsors from 13 states, including 12 Republicans, 4 Democrats, and 1 Independent.

Even though both NMPF and IDFA have shown support for the measure, a bit of resignation can be sensed — riding the overwhelming House vote as enough progress for one legislative session. After taking bows for the performance of the bill in the House, representatives of both NMPF and IDFA – while speaking at winter meetings – have indicated a prevailing view that Senate opposition to S. 1957, is a big barrier.

They say they are working to get the science in front of the Dietary Guidelines Committee, which has been tried before – over and over.

The DGA committee operates under a USDA that does not want whole milk options in schools or SNAP or WIC. This same USDA is proposing to remove chocolate milk options from schools, except for senior high students, and is proposing to reduce WIC milk by 3 gallons per recipient per month. This same USDA projects 20 billion more pounds of milk will be produced in the U.S. by 2030, according to IDFA CEO Michael Dykes, presenting future trends at the Georgia Dairy Conference in Savannah.

Seeds of doubt about the whole milk bill are being sown among farmers. Some asked me recently if their co-ops will lose money on the deal.

Last week, we discussed ‘Confusion’ — the first of 3 C’s that are facing the whole milk bill within the dairy industry.

This week we look at the second C: ‘Consternation’ — a fancy word for fear.

“What will they do with all of our skim?” farmers asked me at a recent event. Is this something they are hearing from a milk buyer or inspector?

Here are some facts: Whole milk sales move the skim with the fat — leaving some of the fat through standardization, but not leaving any skim. Therefore, an increase in whole milk sales does not burden the skim milk market.

Surely, the practice of holding schoolchildren hostage to drinking the byproduct skim of butter and cream product manufacturing is a poor business model if we care about childhood nutrition, health, and future milk sales.

Furthermore, the market for skim milk powder and nonfat dry milk is running strong as inventories are at multi-year lows in the U.S. and globally.

Cheese production, on the other hand, is what is cranking up, and it has been the market dog for 18 months. Like whole milk sales, cheesemaking uses both fat and skim. But cheesemaking leaves byproduct lactose and whey, and it can leave some residual fat depending on the ratios per cheese type.

Things are pretty bad for farmers right now in cheesemilk country. Some tough discussions are being had around kitchen tables. The 2022 Ag Census released last week showed the dire straits for farmers nationwide over the last five years as the number of U.S. dairy farms declined below 25,000, down a whopping 40% since 2017.

Wouldn’t an increase in whole milk sales through the school milk channels help pull some milk away from rampant excess cheese production that is currently depressing the Class III milk price, leading to price divergence and market dysfunction?

While there is no one data source to specifically document the percentage of the milk supply that is sold to schools, the estimates run from 6 to 7% of total fluid milk sales (Jim Mulhern, NMPF, 2019), to 8% of the U.S. milk supply (Michael Dykes, IDFA, 2023), to 9.75% of total fluid milk sales (Calvin Covington, independent analysis, 2024).

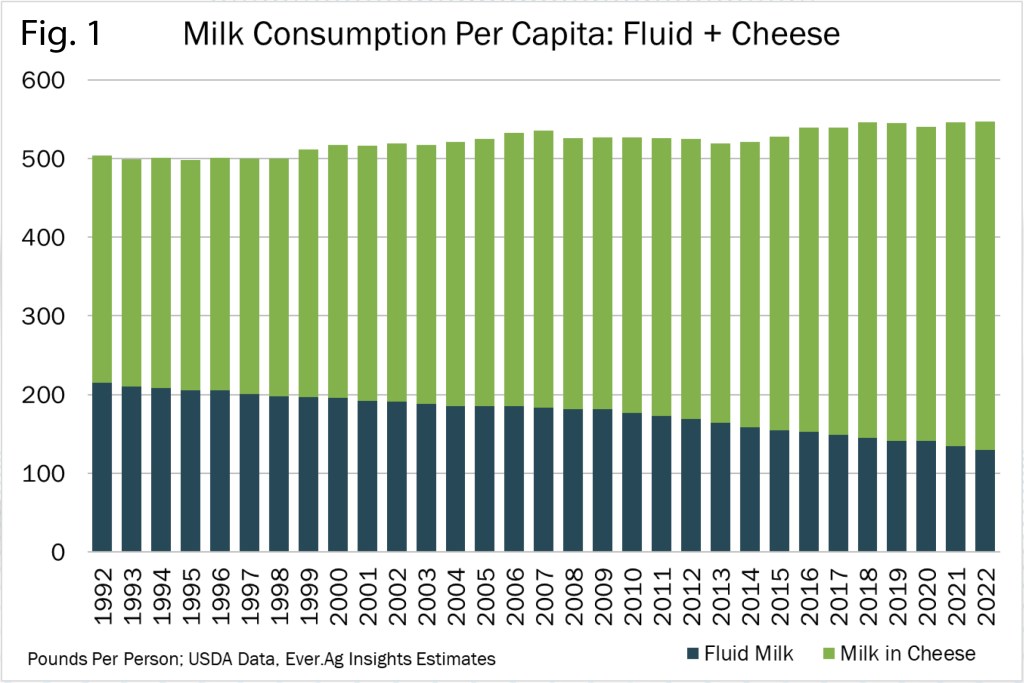

If even half of these sales became whole milk sales, it could modestly positively impact the amount of excess cheese being made even as processors say they plan to make more cheese because people eat more of their milk than are drinking it. (Fig. 1)

Meanwhile, the cheese price is under so much downward price pressure that there is a $2 to $4 divergence of Class IV over Class III causing farmers to lose money under the ‘averaging’ formula for Class I milk. In many parts of the country, farmers lose additional money when the milk that is used in Classes II and IV is depooled out of FMMOs.

Without the ‘higher of’ pricing mechanism that was in place from the year 2000 until May 2019, Class I can fall below the higher manufacturing price, removing incentive to pool, which leaves pooled producers with smaller payments for their milk and leaves the decision about what to pay depooled farmers up to the processors after they’ve succeeded in reducing the benchmark minimum by depooling.

Ultrafiltered (UF) milk represents 2.4% of fluid milk market share, having grown by more than 10% per year for four years with sales up 7.7% in 2023 vs. 2022, according to Circana-tracked market data shared by Dykes.

UF milk is also cheese-vat-ready-milk with capability to remove not just the lactose but also the whey as permeate at the front end for use in distilleries that are now funneling lactose into ethanol production in Michigan and whey into alcoholic beverages in Michigan and Minnesota.

Processors want farmers to do “a tradeoff” to decide how much revenue comes to their milk checks and how much goes to processing investments for the future. The future is being dictated by where we are in fluid milk consumption relative to cheese production.

This is one reason IDFA and Wisconsin Cheesemakers, as well as NMPF, had proposals asking USDA to increase the processor credits (make allowances) that are embedded in the dairy product price formulas. IDFA and Milk Innovation Group also put forward other proposals to further reduce regulated minimum prices.

We wonder with these new processing investments, how is it that the make allowances are too small? Only bulk butter, nonfat dry milk, dry whey, 40-lb block Cheddar and 500-lb barrel cheese (yellow not white) are surveyed for the circular class and component price formulas. Everything else that doesn’t meet CME spec for these specific product exchanges is excluded.

This means the costs to make innovative new products and even many bulk commodity-style products, such as bulk mozzarella, unsalted butter, whey protein concentrate and skim milk powder, can be passed on to consumers without being factored back into the FMMO regulated minimum prices paid to farmers.

If market principles are applied, processors wanting to encourage more milk production, to make more cheese, would pay more for the milk – not less. But when the margin can be assured with a make allowance that yields a return on investment, all bets are off. Cheese gets made for the ‘make’ not the market.

We saw processors petition USDA in the recent Federal Milk Marketing Order hearing to reduce the minimum prices in multiple ways so they can have the ability to pay market premiums to attract new milk. This would be value coming out of the regulated FMMO minimum price benchmark for all farmers to get added back in by the processors wherever they want to direct it.

Cheese is in demand globally, and the U.S. dairy industry is investing to meet this. Dykes told Georgia producers that processors want to grow and producers want to grow. He wasn’t wondering what to do with all of the skim when he asked: “Where will the milk come from for the over $7 billion in new processing investments that will be coming online in the next two to three years?”

This is happening, said Dykes, “due to market changes from fluid milk to more cheese production (Fig. 1). There’s a lot of cheese in those plans. With over $7 billion in investment… These are going to be efficient plants. You’re going to see consolidation. If you are part of a co-op, you’re going to decide how much (revenue) comes in through your milk check and how much goes into investment in processing for the long-run, for the future. That’s the debate your boards of directors will have.”

Even the planned new fluid milk processing capacity is largely ultra-filtered, aseptic and extended shelf life, according to Dykes.

“That’s the direction we are moving,” he said. “We are seeing that move because as we think about schools, are we still going to be able to send that truck driver 20 miles in any direction with 3 or 4 cases of milk 5 days a week? Or do we do that with aseptic so they can store it and put it in the refrigerator one night before, and get some economies of scale out of that, and maybe bring some margin back to the business?”

As the Class III milk price continues to be the market dog, we don’t see milk moving from Class III manufacturing to Class IV, perhaps because of the dairy processing shifts that have been led by reduced fluid milk consumption.

Allowing schoolchildren to have the choice of whole milk at school is about nutrition, healthy choices, future milk consumers, and the relevance of fresh fluid milk produced by local family farms in communities across the country. Having a home for skim does not appear to be the primary factor affecting milk prices where Class III is dragging things down.

Bottomline, dairy farmers should have no consternation (fear) over what processors are going to do with “all of that skim” once they are (hopefully) allowed to offer schoolchildren milk with more fat.

Next time, we’ll address the third ‘C’ – Competition – If kids are offered whole milk in schools, will it reduce the butterfat supply and impact the industry’s cheese-centered future?

A final note, just in case the question about ‘what to do with all that skim’ still bothers anyone… What’s wrong with animal feed markets for skim milk powder? Protein is valuable in animal health, there are livestock to feed, and people spend major bucks on their pets too. Did you know dog treats made with nonfat dry milk powder, flour and grated cheese are a thing?

That idea got a good laugh from those farmers when I suggested it.

However, Cornell dairy economist Dr. Chris Wolf noted recently how China’s purchases are what drive global skim milk powder and whey protein prices, and that much of that market for both is to feed… you guessed it… Pigs.

By Sherry Bunting, from Farmshine May 4, 2018

By Sherry Bunting, from Farmshine May 4, 2018