By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, May 17, 2024

WASHINGTON – House Ag Committee Chairman Glenn ‘GT’ Thompson (R-Pa.) says the bipartisan farm bill has reached a milestone and holds the potential for being transformational.

The chairman’s mark, released ahead of committee markup set for May 23, demonstrates the listening that went on in his busy schedule traveling to 40 states and one territory for 85 listening sessions over the past two years.

“We are hopeful that the House Ag Committee markup of this chairman’s mark legislation helps feed the momentum to get this farm bill done,” said Chairman Thompson in a May 14 Farmshine phone interview.

There are important highlights here, including reforms to the Dietary Guidelines process for greater transparency and accountability with new checks and balances, as well as language to expand the reach, funding and impact of the dairy incentive and school meal programs by including full fat fluid milk, flavored and unflavored, as seen in H.R. 5099 and H.R. 1147 (Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act).

“I was able to work with Dr. Virginia Foxx (chair of the House Education and Workforce Committee), and they will be providing a waiver after we mark this bill up, so we will be able to include Whole Milk for Healthy Kids in the farm bill,” Thompson shared.

He has previously stressed that, “This is about our kids and the outdated and harmful demonization of milkfat.”

“When we get to conference (with the Senate), it could be an issue, but Whole Milk for Healthy Kids passed the House by a 330 vote. I am intent on getting this provision over the finish line.

“It may be the most important thing we do out of many things in this farm bill for dairy farmers,” he said.

Other dairy subtitle provisions

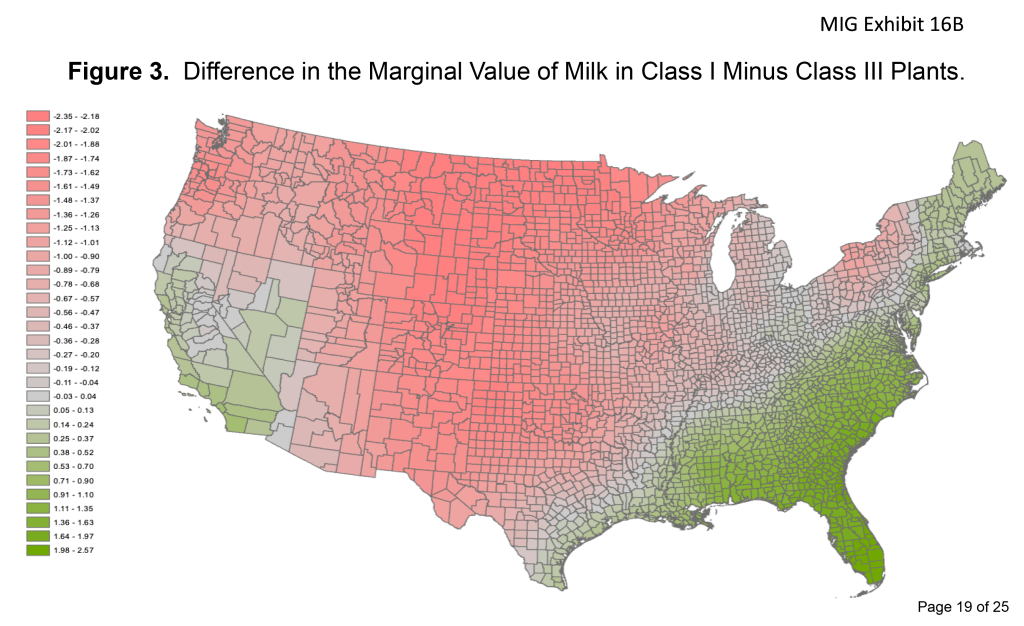

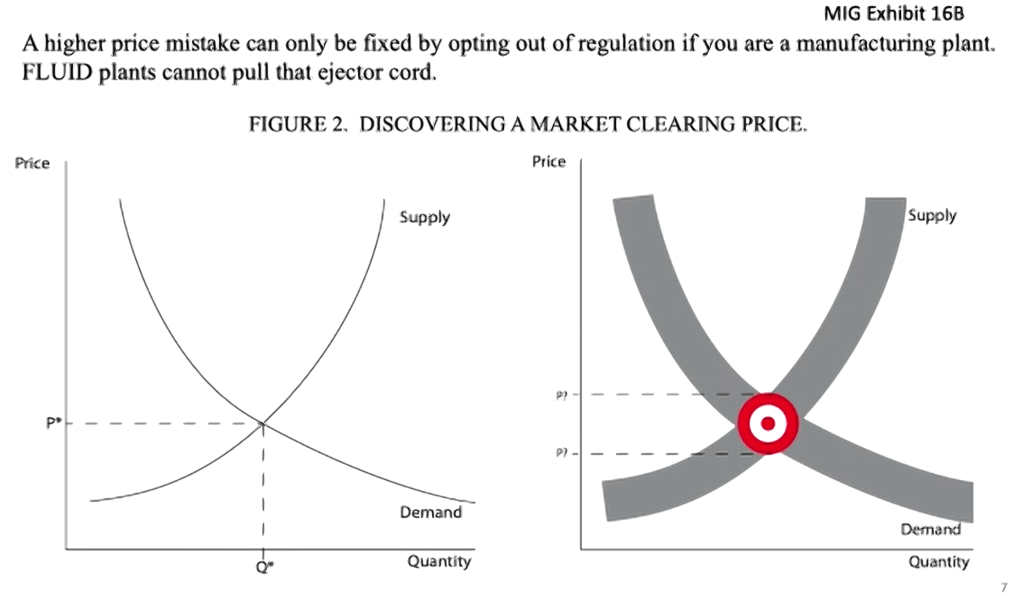

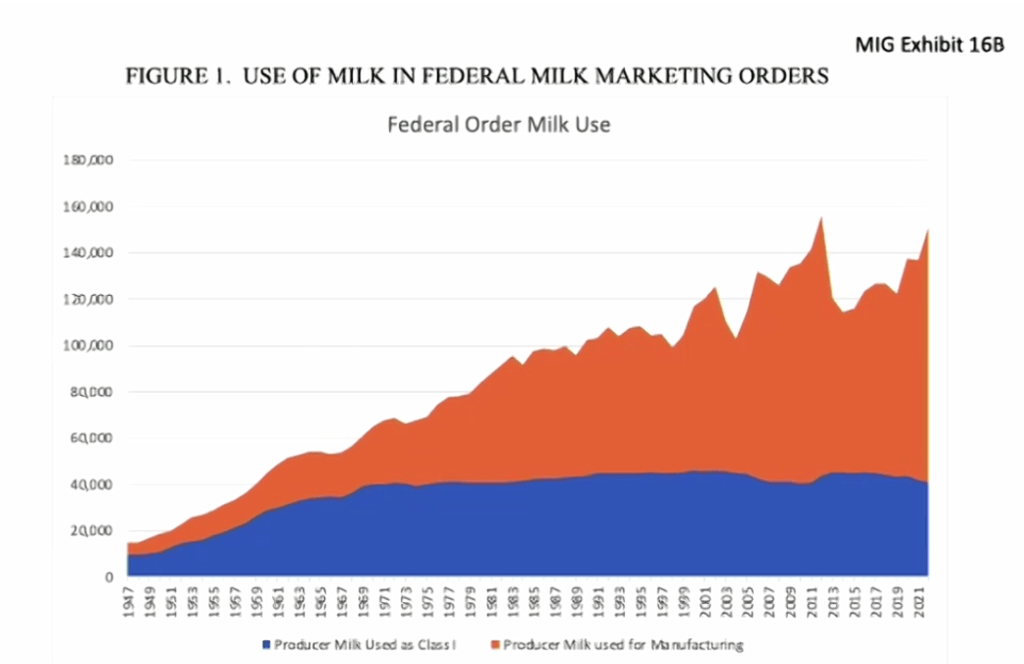

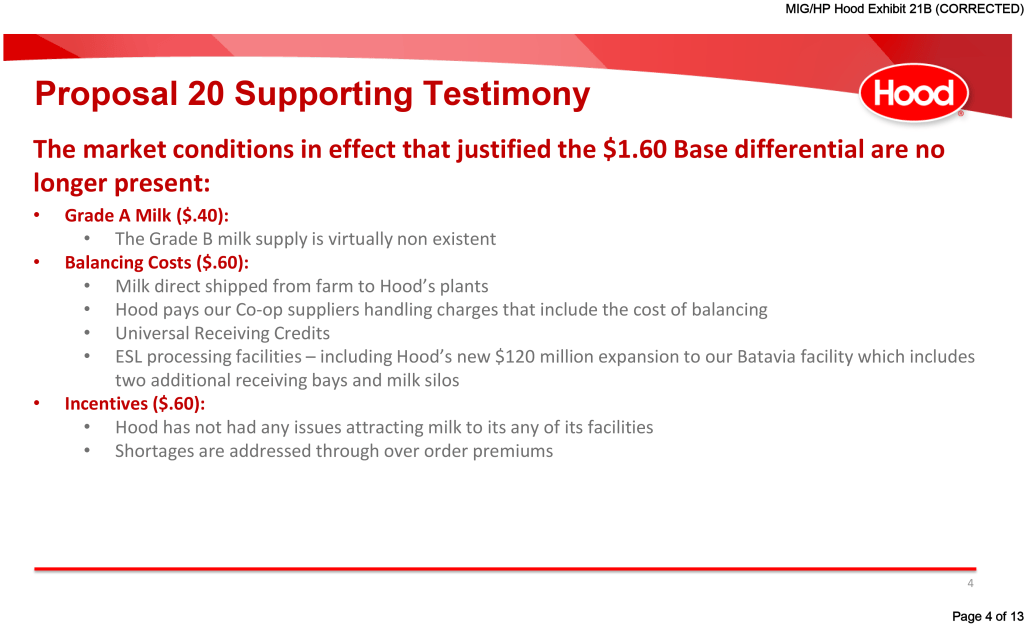

The dairy subtitle includes language to return the Class I ‘mover’ price to the ‘higher of’ calculation instead of the ‘average plus 74 cents’ that was implemented in May 2019.

“We obviously recognize that USDA has now gone through an extensive hearing process, and will honor what USDA comes up with, which will supersede what we’re doing,” Thompson reported. “But it was the Ag Committees in the Congress through the 2018 farm bill that eliminated the ‘higher of’ language, which has been followed by significant unanticipated losses.”

Language has also been included to mandate biennial cost of processing surveys. This also appears in the Senate farm bill.

Processors making products used in Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) formulas would participate in processing cost surveys every two years. In addition to reporting costs for those products, the Dairy Pricing Opportunities Act language that is rolled into the farm bill proposal states that the cost and yield information for all products processed in the same facility be included. (Note: This would ensure accurate allocation of plant costs that apply just to the products that are actually used in the FMMO pricing formulas so that the costs to process other value-added products that are not included in FMMO pricing, but are made in the same plant, do not influence future ‘make allowance’ hearings.)

These cost surveys would be published for the purposes of informing the regulatory or administrative (hearing) process for the establishment of pricing rules (such as determining how to use that published information to set ‘make allowance’ levels that are embedded in FMMO pricing formulas).

The dairy subtitle also expands the Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) tier one cap on annual milk production history from 5 million pounds to 6 million pounds, similar to the Senate bill.

It also includes language for updating DMC production history and provides a 25% discount in premium costs for any producer signing up for all five years of DMC coverage.

“That’s quite a savings,” Thompson observed.

IRA funds included without ‘climate sideboards’

In the Conservation Title, the chairman’s mark brings Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) conservation funds into the farm bill baseline without the ‘climate sideboards’ and arbitrary measures that ride along in the Senate version.

“All conservation programs, as long as they are locally-led and voluntary, contribute to climate and carbon sequestration. What the IRA legislation did is make it overly prescriptive with a lot of practices we know are successful not being eligible for these conservation dollars.

“We believe that the principles of locally-led and voluntary are a huge part of what has made conservation programs so successful. Agriculture sequesters 6.1 gigatons of carbon annually, over 10% more than we emit,” said Thompson.

Timelines matter

There are a couple reasons timelines matter in getting this farm bill done. The IRA funding is one of them.

“Number one is the American farmer is struggling right now. The chairman’s mark, as we prepared it in the House Committee, will be of great service to them as producers of food, and to struggling families as consumers of food, quite frankly,” said Thompson.

“The other reason timelines matter is these IRA dollars. As the Secretary of Agriculture continues to push those dollars forward, the original $19 billion – between what he already spent and what the CBO projects he will not be able to spend – that number is now down to $14 billion,” Thompson explained. “That’s opportunity lost for the future, unless and until we pass and reauthorize the farm bill and roll those dollars into its baseline.”

Thompson continued, explaining that, “Every dollar in IRA conservation funds spent between now and the passage of the farm bill is a dollar lost to the baseline for the future. One of the flaws of the IRA is these conservation dollars expire in 2031. Whatever we bring into the farm bill – into the baseline – is there for perpetuity. It will be there for the 2050 and 2055 farm bills. That’s smart, and it’s good for agriculture and great for conservation.”

The Senate proposal also brings IRA conservation funds into the farm bill baseline, but puts climate requirements on these funds, especially in regard to methane.

Tripartisan effort produces nutrition cost-savings, not cuts

“My chairman’s mark is built on solid tripartisan input from Republicans and Democrats and the hardworking people of American agriculture,” Thompson affirmed. “The Senate proposal is a partisan proposal. They did not bring Senate Republicans to the table.”

In his May 10 open letter, Chairman Thompson stated that his door is always open.

“There exists a few, loud armchair critics that want to divide the Committee and break the process. A farm bill has long been an example of consensus, where both sides must take a step off the soapbox and have tough conversations,” he wrote. “The 2024 farm bill was written for these precarious times and is reflective of the diverse constituency and narrow margins of the 118th Congress. Each title takes into consideration the varying opinions of all who produce as much as those who consume. It is not one-sided, it does not favor a fringe agenda, and it certainly does no harm to the programs and policies that feed, fuel, and clothe our nation.”

Case in point, the CBO has scored the House farm bill chairman’s mark to save $28 to $29 billion in the Nutrition Title.

“Some would have you believe we are cutting $28 to $29 billion from feeding struggling families, but we are not,” Thompson declared. “There are no cuts to individual SNAP benefits in this bill. My Democratic colleagues say we are cutting by that much, but the CBO score on my proposal reflects cost savings from increased efficiencies, reduced fraud, and things that better meet the needs of families struggling in poverty.”

Justifiably proud of the intense work he and his committee have done on the nutrition programs lightning rod that makes up more than 80% of the farm bill baseline, Thompson said his proposal actually “creates a fire wall so that a future right-leaning administration would not be able to arbitrarily cut benefits either. It exercises our Article I prerogative on how we do market basket analysis, keeps the variables and the cost of living. These things are significant factors.”

His proposal also expands access to a couple populations not eligible for SNAP in the past, including families with adult children in school up to age 21 (not 18). In the past, their part-time jobs affected family eligibility.

Putting the farm back in the farm bill

The Commodities and Crop Insurance Titles also engaged input from farmers, farm groups and industry. On reference prices, Thompson said the Senate bill picks three crops and puts in a 5% increase for base acreage.

“In our proposal, we’ve worked with the stakeholders. We’ve done the math, the financial and risk analysis on what is needed.”

This includes a more commodity-specific update to reference prices and granting the Secretary of Agriculture authority to expand base acres.

“We have been committed to putting the farmer back into the farm bill commodities title,” he said.

This scratches the surface of what is included in the farm bill chairman’s mark. An overview and title by title summary are available at https://agriculture.house.gov/farmbill/

When asked about what other dairy topics could come up during markup, Thompson said he wouldn’t be surprised to see other amendments in committee.

“There are some labeling issues that are not in our purview or jurisdiction but come under the Energy and Commerce Committee. We could get the ball rolling, but we would need them to get on board for that to go forward,” he said.

Reflecting on the milestone this week, Thompson answered our question about what he’s most proud of to this point.

“The fact that this farm bill was built using the input of American farmers, ranchers, and foresters, and it reflects what their priorities are and what their needs are, and the fact that as I look at the chairman’s mark and all 12 titles according to the goal placed early on, two years ago as I started my leadership of this process:

“This will be not only a highly effective farm bill for our producers, processors and all of us who consume food, it will be transformational,” he said.

-30-

In fact, Rusty penned these words in a Facebook post 10 days before Christmas just after the auction signs went up, thanking their network of family, friends and church family and offering to others a glimpse of the hope and faith that remain strong – knowing so many farmers are wrestling with similar difficulties and decisions.

In fact, Rusty penned these words in a Facebook post 10 days before Christmas just after the auction signs went up, thanking their network of family, friends and church family and offering to others a glimpse of the hope and faith that remain strong – knowing so many farmers are wrestling with similar difficulties and decisions.

MOUNT JOY, Pa. — Another rainy day. Another family selling their dairy herd. Sale day unfolded November 9, 2018 for the Nissley family here in Lancaster County — not unlike hundreds of other families this year, a trend not expected to end any time soon.

MOUNT JOY, Pa. — Another rainy day. Another family selling their dairy herd. Sale day unfolded November 9, 2018 for the Nissley family here in Lancaster County — not unlike hundreds of other families this year, a trend not expected to end any time soon.

“It was a privilege to make the announcements on those 425 head, and I was impressed with the turnout of buyers, friends and neighbors as the tent was packed,” said Brandt after the sale. “The cows were in great condition and you could tell management was excellent.”

“It was a privilege to make the announcements on those 425 head, and I was impressed with the turnout of buyers, friends and neighbors as the tent was packed,” said Brandt after the sale. “The cows were in great condition and you could tell management was excellent.” “It’s getting real,” says Mike. “Everyone is focused on survival, but we can see others are shook, not just for us, but because they are living it too.”

“It’s getting real,” says Mike. “Everyone is focused on survival, but we can see others are shook, not just for us, but because they are living it too.”

The Riverview herd had good production and exceptional milk quality. Making around 25,000 pounds with SCC averaging below 80,000, Mike is “so proud of the great job Audrey has done. Without that quality, and what was left of the bonus, we would have had no basis at all,” he says, explaining that Audrey’s strict protocols and commitment to cow care, frequent bedding, and other cow comfort management — as well as a great team of employees — paid off in performance.

The Riverview herd had good production and exceptional milk quality. Making around 25,000 pounds with SCC averaging below 80,000, Mike is “so proud of the great job Audrey has done. Without that quality, and what was left of the bonus, we would have had no basis at all,” he says, explaining that Audrey’s strict protocols and commitment to cow care, frequent bedding, and other cow comfort management — as well as a great team of employees — paid off in performance. Trying to stay afloat — and jockeying things around to make them work — “has been horrible,” said Nancy. She does the books for the farm and has a catering business.

Trying to stay afloat — and jockeying things around to make them work — “has been horrible,” said Nancy. She does the books for the farm and has a catering business.

Author’s Note: Amazing how even more true this piece from 2016 rings today in 2018. This “Growing the Land” column was originally published two years ago in the July 20, 2016 edition of the Register-Star in New York’s Hudson Valley. Indeed, it is still timely today, two years later, as summer memories are still grand and dairy farm milk price margins are still poor — and as a society we continue to incrementally lose the soul of our food, which we may not even fully appreciate or realize is happening.

Author’s Note: Amazing how even more true this piece from 2016 rings today in 2018. This “Growing the Land” column was originally published two years ago in the July 20, 2016 edition of the Register-Star in New York’s Hudson Valley. Indeed, it is still timely today, two years later, as summer memories are still grand and dairy farm milk price margins are still poor — and as a society we continue to incrementally lose the soul of our food, which we may not even fully appreciate or realize is happening.