By Sherry Bunting, Farmshine, Friday, Oct. 4, 2019

MADISON, Wis. – Grabbing the headlines from a town hall meeting with U.S. Ag Secretary Sonny Perdue during the opening day of the 53rd World Dairy Expo, here in Madison, Wisconsin, was a comment the Secretary made about the viability of small family farms.

He was asked whether they will survive. To which he answered, “Yes, but they’ll have to adapt.”

In fact, the Secretary said that the capital needs and environmental regulations that impact farms today make it difficult for smaller farms to survive milking 50 to 100 cows.

“What we’ve seen is the number of dairy farms going down, but the number of dairy cows has not,” said Perdue. “Dairy farms are getting larger, and smaller farms are going out.”

But in additional discussion, Perdue said that consumers want local products. He said that marketing local, even without the buzzwords, can be done successfully to bring value to farms.

He noted two things about dairy farms. First, they can’t be sustainable without profitability and second, he described the dairy industry as prone to oversupply.

Picking up on these comments, recently retired northwest Wisconsin dairy producer Karen Schauf said Farm Bureau is looking at the Federal Milk Marketing Orders and how make some adjustments on the milk pricing.

“But what we really need to do is balance supply and demand of dairy products much closer,” she said. “I would ask if you would support a flexible mandatory supply management system to help producers keep that supply and demand in closer relationship.”

Perdue asked if she wanted the short answer or the long answer, stating that when his children want a quick answer, it’s always “no.”

Schauf replied, “Mr. Secretary, I just want you to think about it.” The subject went no further.

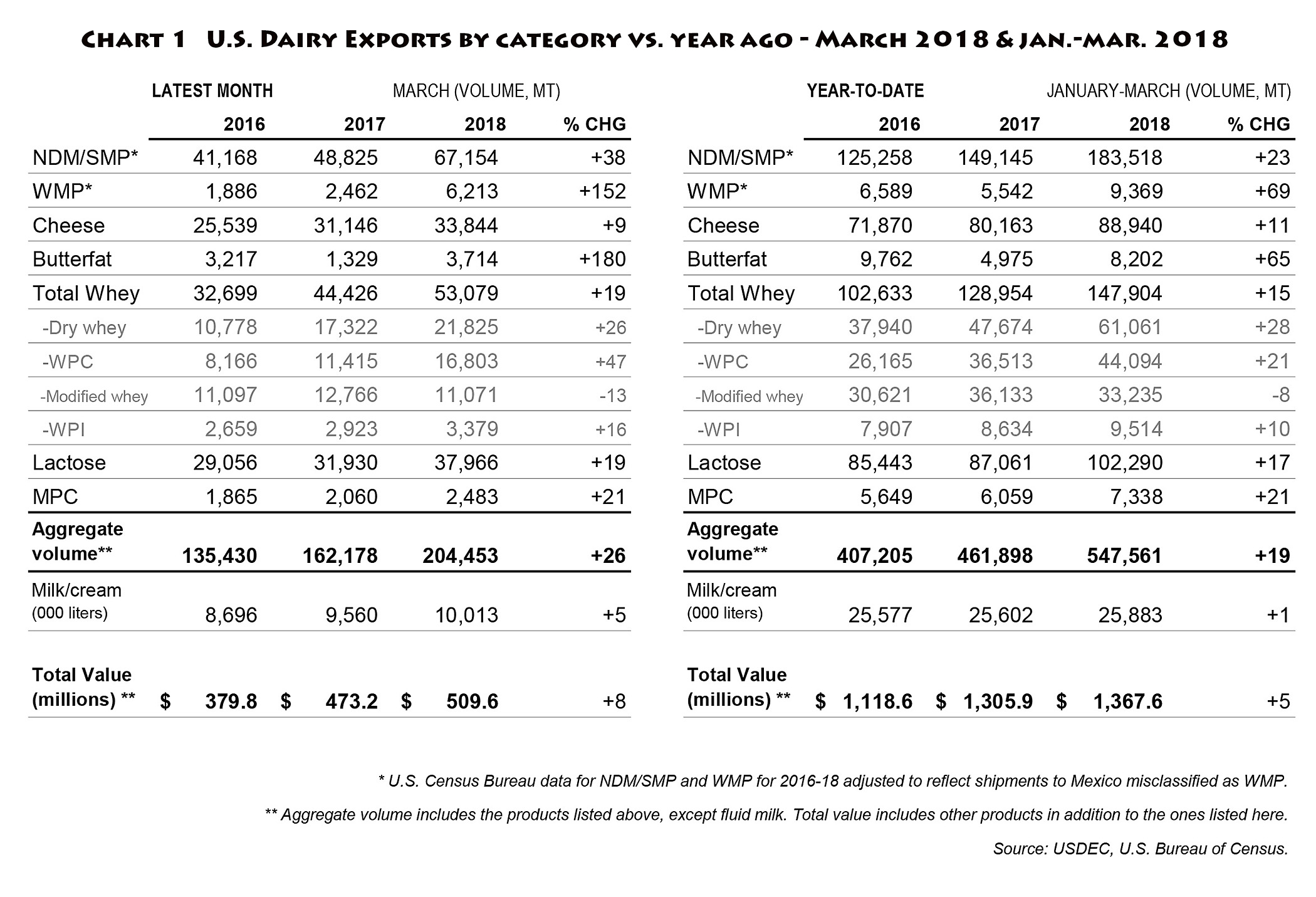

At another point in the questioning, a Wisconsin producer observed the disheartening price levels and said last year was a record high level of exports, while prices to farmers were worse than this year and worse than 2017.

He noted that exports hit 17.6% of milk produced, and settled out at 16% last year, which is a record, but his milk price averaged $14.60. He went on to say that, “our exports are off 2% this year, but I’ll probably come close to an average of $17 on my milk price.” He also noted that National Milk Producers Federation recently put out a press release stating 2015-18 as record years in domestic dairy consumption.

“This is all good,” the dairy farmer said, “but in Wisconsin we are losing 2.5 farms per day and I think the call centers are full with distressed farmers calling in, so beyond trade and some of these things you promote at the federal level, what can we be looking at so we never experience another five years like this?”

Perdue thanked the producer for his facts and said it is amazing that things “can be good and yet feel so bad.” He acknowledged that dairy has been under the most stress, and he said that the 2018 Farm Bill did “exactly the right thing” with the new Dairy Margin Coverage. He pointed out that this coverage is specifically in place for smaller dairy farms.

“Milk prices are cyclical, and I think we’ve met that trough, and things will improve for 2020,” said Perdue.

Referencing the 2% milk on the table in front of him, Perdue said: “You pretty much know what happened to milk in our schools, with the whole milk and the accusations about fat in milk. We hope to get some benefit, maybe, from the Dietary Guidelines this year, which drive a lot of this conversation.”

Noting that USDA “is leading” the Dietary Guidelines along with Health and Human Services, the Secretary said: “We have a great panel and they will bring together the best scientific facts about what is healthy, wholesome and nutritious for our young people and our older people and all of us, so we’re looking forward to that.”

On trade, the Secretary was hopeful. He cited the recent trade agreement with Japan, but did not have exact numbers for dairy, just that it will be beneficial for dairy. On China, he was optimistic and said progress is being made, but that it has been important to take this stand because they have been “cheating” and are “toying with us.”

One area he mentioned in regard to trade with China is that U.S. agriculture has become too dependent on “what China will do.” He said the administration is really working on trade with other nations in the Pacific and elsewhere that do not represent such large chunks as to disrupt or distort markets as they come in and out of the game. This has held true for dairy exports from the U.S., which are rising in so many other parts of the world.

On the USMCA, Perdue said the outcome will depend on whether the Speaker of the House brings it to the floor for a vote. “It will pass both caucuses, but it has to come to the floor. We hope to see that happen by the end of the year, that distractions won’t get in the way,” said Perdue.

The town hall meeting covered a wide range of other questions and comments, and often, the answer to the toughest questions was “it’s complicated and we’ll be happy to look into it.”

On the Market Facilitation Program, several had questions about why alfalfa-grass is not included as a crop, just straight alfalfa. Perdue explained that alfalfa is a crop exported to China and that the crops in the eligible crops for MFP payments have to be “specifically enumerated.”

As with other questions, he emphasized the local FSA Committees who implement some of the more subjective pieces of these programs that farmers can appeal to their local committees if they’ve been denied.

In the prevent plant flexibilities for harvesting forage, Perdue said USDA is looking at this as perhaps something to be made permanent – the ability to harvest forage on prevent plant acres in September rather than waiting until Nov. 1.

Paul Bauer from Ellsworth Cooperative Creamery focused his comments on the spread between Cheddar blocks and barrels on the CME and how this is deflating the price paid to dairy farmers – especially in Wisconsin – but also across the U.S. because of how it affects the Class III pricing formula.

“For the last four years, the spread between blocks and barrels has been greater than 12 cents. Historically, the spread has been three cents or less per pound for the prior 50 years,” he said, noting that the spread at the end of the previous week stood at just shy of 35 cents per pound!

“The common thought is that this bounces back to a normal range, but it doesn’t,” said Bauer, noting that last year’s average spread cost dairy farmers 60 cents per hundredweight on their milk price. “Those farmers who ship to barrel plants, such as Ellsworth Cooperative Creamery, were affected by $1.20/cwt on their milk price due to this wide spread.

He noted that last week’s 34 ¾ cent spread between blocks and barrels cost dairy farmers $3.40/cwt, which is 20% of their base price.

Acknowledging that this is a complex issue, Bauer asked the Secretary if USDA will take the first step and admit there is a problem instead of “rolling their eyes because of the complexity.”

“This is unfavorable to our farmers and unfair to our producers,” said Bauer, explaining that all dairy products are priced off the block-barrel on the CME, ultimately.

“It’s important to get it right,” said Bauer, explaining that it is a problem when the industry can build barrel inventory to create this divergence in block / barrel prices on the CME, which in turn suppresses the price they pay to producers for the milk used in a multitude of other “modern” products.

“Barrel production comes from 16 plants (nationwide), and represents 6% of the nation’s dairy supply, and yet has had a 58% of the impact on all producers’ milk checks,” said Bauer. “When the system is out of sync, that negative value affects us all.

“It’s time for USDA to formally take action and for the data to come to light that are influencing the market,” said Bauer.

He explained that the system is there to protect farmers and local buyers but is now being influenced by foreign cooperatives that keep one product – barrels – in oversupply in order to keep milk prices lower for products that are priced off the higher blocks in short supply.

Bauer said the secrecy of buyers and sellers on the CME protects this practice. “It’s time to update the system to keep up with modern times to protect our farmers and our food supply also in terms of quality and safety.”

Secretary Perdue drew laughter when he asked Bauer: “Would you repeat the question?” But he took it in and asked for a written copy of the question to look into it. Perdue said that concerns are often raised about the Federal Milk Marketing Orders.

“They are a fairly complex issue, but we’d be happy to investigate. The government’s role in general is to be the balance between the producer and the consumer and ensure no predatory pricing practices,” said Perdue, “while not interfering with commerce and contracts.”

He gave the example of the fire at the Tyson beef plant in Holcomb, Kansas and the staggering loss to cattle prices since that fire over a month ago that have resulted in packer margins at an unprecedented $600 per head.

“We saw a spike in the delta – the difference between the live cattle price and the boxed beef price at historic highs, and we are investigating that, to make sure there was no pricing collusion,” said Perdue. “I’ve asked those packers to come in and give me their side of the story. That’s the role of USDA.”

Pete Hardin of the Milkweed asked about the cell cultured meat, citing a publicized comment by the Secretary last summer pointing to the value of this science. Hardin asked if any studies have been done on the safety of this technology.

Perdue did not know if any specific studies have been done, and he confessed to trying an Impossible Burger, adding “There’s now one restaurant I no longer attend.”

He stressed that these products cater to people who aren’t eating meat anyway for whatever reason, and he said: “In the end, consumers will be the ones to choose.”

Picking up on this in a separate question about how dairy and livestock farms can remain viable with all of the imitation products competing for consumers, the Secretary observed that, “As farmers we are independent and like to sit behind the farm gate and produce the best, most nutritious food in the world at the lowest cost anywhere in the world, but we’ve never told the story.

“It’s up to every one of us to speak out locally and statewide and federally, nationally in that area and tell the story of what’s happening. No longer can we hide behind the curtain,” said Perdue.

“There’s a growing movement about knowing how you do your job, what’s in the milk, how the animals are treated, and there’s no going back from that. We have to engage with consumers. We have to tell the story loudly and proudly.”

-30-

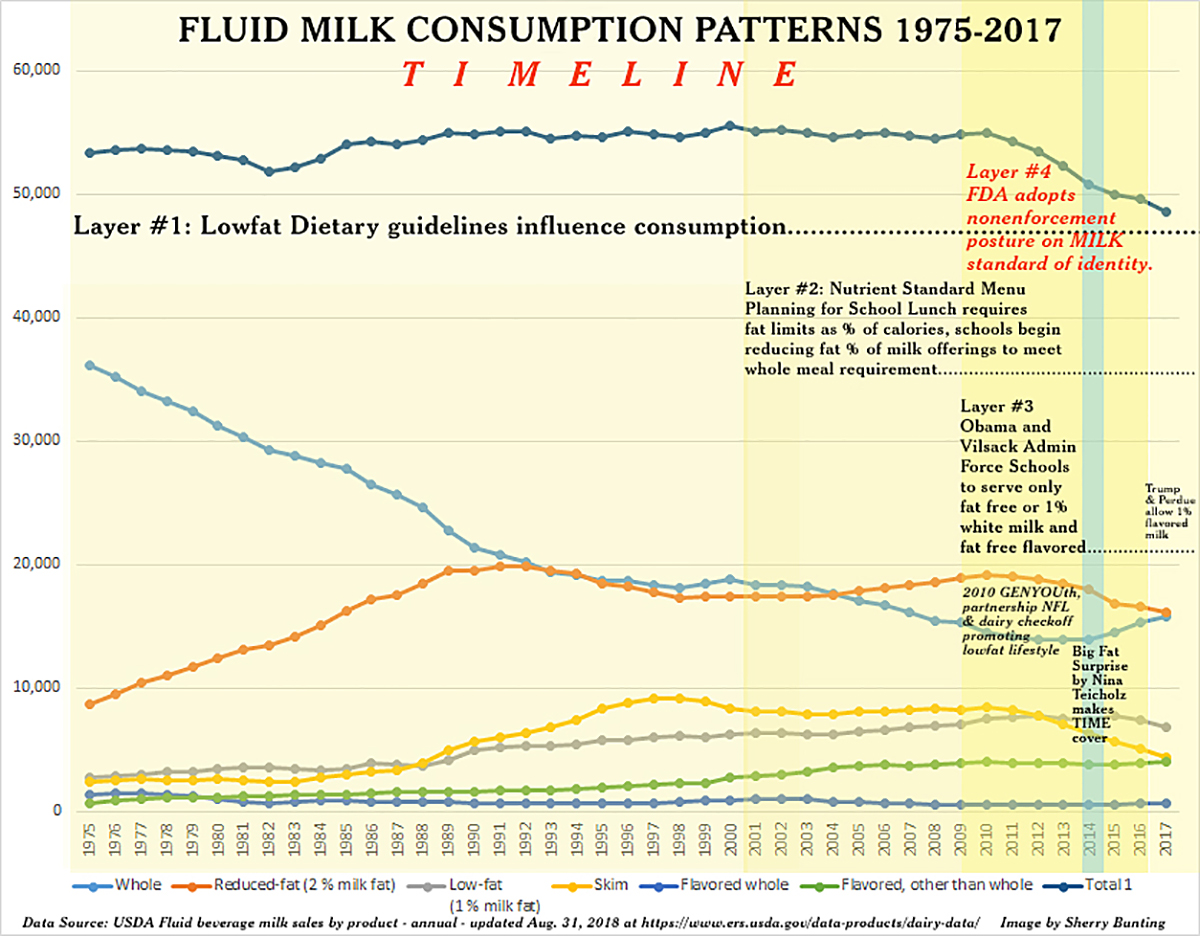

That is, until we hit 2009-10, when the third and fourth layers (see Chart 1 above) were added to the lowfat-push — that consequently pulled total fluid milk sales into the bucket at the same time that exports began their rapid ascent.

That is, until we hit 2009-10, when the third and fourth layers (see Chart 1 above) were added to the lowfat-push — that consequently pulled total fluid milk sales into the bucket at the same time that exports began their rapid ascent.

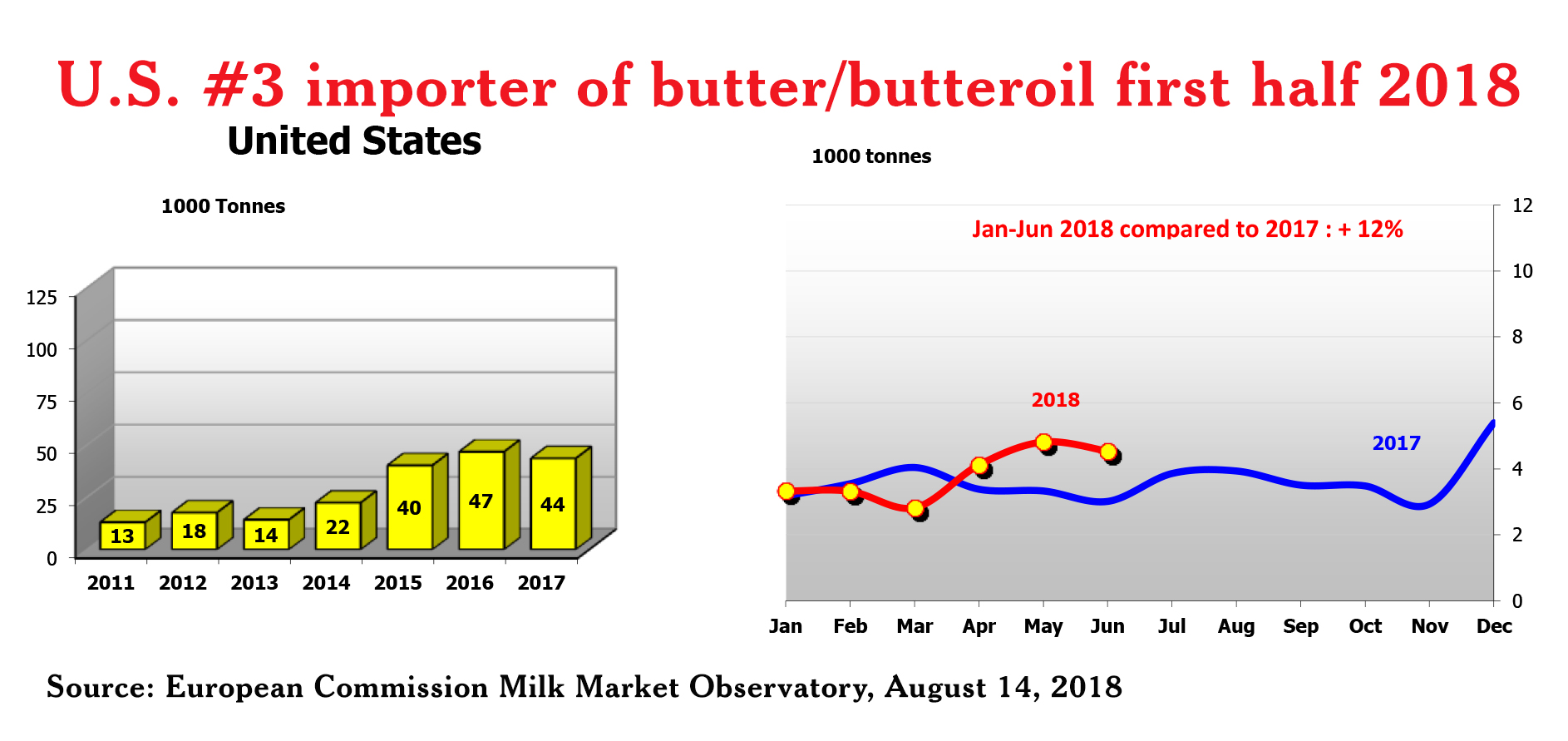

By Sherry Bunting, originally published in Farmshine, June 7, 2018 and examines the utilization of domestic Class I fluid milk vs. exported commodities during the worst three months of pricing at the beginning of 2018, but the trends show how FMMO pricing no longer provides the value to farmers for their milk as exports increase. Read Global Thoughts

By Sherry Bunting, originally published in Farmshine, June 7, 2018 and examines the utilization of domestic Class I fluid milk vs. exported commodities during the worst three months of pricing at the beginning of 2018, but the trends show how FMMO pricing no longer provides the value to farmers for their milk as exports increase. Read Global Thoughts  The total “official” U.S. Class I utilization for 2017 was 26.1%, down nearly 10% from 35.9% in 2009, according to USDA figures.

The total “official” U.S. Class I utilization for 2017 was 26.1%, down nearly 10% from 35.9% in 2009, according to USDA figures. MOUNT JOY, Pa. — Another rainy day. Another family selling their dairy herd. Sale day unfolded November 9, 2018 for the Nissley family here in Lancaster County — not unlike hundreds of other families this year, a trend not expected to end any time soon.

MOUNT JOY, Pa. — Another rainy day. Another family selling their dairy herd. Sale day unfolded November 9, 2018 for the Nissley family here in Lancaster County — not unlike hundreds of other families this year, a trend not expected to end any time soon.

“It was a privilege to make the announcements on those 425 head, and I was impressed with the turnout of buyers, friends and neighbors as the tent was packed,” said Brandt after the sale. “The cows were in great condition and you could tell management was excellent.”

“It was a privilege to make the announcements on those 425 head, and I was impressed with the turnout of buyers, friends and neighbors as the tent was packed,” said Brandt after the sale. “The cows were in great condition and you could tell management was excellent.” “It’s getting real,” says Mike. “Everyone is focused on survival, but we can see others are shook, not just for us, but because they are living it too.”

“It’s getting real,” says Mike. “Everyone is focused on survival, but we can see others are shook, not just for us, but because they are living it too.”

The Riverview herd had good production and exceptional milk quality. Making around 25,000 pounds with SCC averaging below 80,000, Mike is “so proud of the great job Audrey has done. Without that quality, and what was left of the bonus, we would have had no basis at all,” he says, explaining that Audrey’s strict protocols and commitment to cow care, frequent bedding, and other cow comfort management — as well as a great team of employees — paid off in performance.

The Riverview herd had good production and exceptional milk quality. Making around 25,000 pounds with SCC averaging below 80,000, Mike is “so proud of the great job Audrey has done. Without that quality, and what was left of the bonus, we would have had no basis at all,” he says, explaining that Audrey’s strict protocols and commitment to cow care, frequent bedding, and other cow comfort management — as well as a great team of employees — paid off in performance. Trying to stay afloat — and jockeying things around to make them work — “has been horrible,” said Nancy. She does the books for the farm and has a catering business.

Trying to stay afloat — and jockeying things around to make them work — “has been horrible,” said Nancy. She does the books for the farm and has a catering business.

By Sherry Bunting, from Farmshine, Sept. 7, 2018

By Sherry Bunting, from Farmshine, Sept. 7, 2018 Emotional town hall meeting in Lebanon, Pa. draws over 200 people urging contract extensions for Dean’s dropped dairies

Emotional town hall meeting in Lebanon, Pa. draws over 200 people urging contract extensions for Dean’s dropped dairies Indeed, a legacy is on the line in Lebanon and Lancaster Counties, as in other communities similarly affected.

Indeed, a legacy is on the line in Lebanon and Lancaster Counties, as in other communities similarly affected. Rick Stehr, a nutritionist and owner of R&J Consulting, directed some of his comments to the significant number of youth in the audience, saying that these farms are where the next generation learns morals, values, work ethic and the joys and failures of life.

Rick Stehr, a nutritionist and owner of R&J Consulting, directed some of his comments to the significant number of youth in the audience, saying that these farms are where the next generation learns morals, values, work ethic and the joys and failures of life. Brent Hostetter, Lebanon County dairy producer: “I am not sure how we are going to handle this going forward. We have put all we have into the farm. Nothing will settle like it should.”

Brent Hostetter, Lebanon County dairy producer: “I am not sure how we are going to handle this going forward. We have put all we have into the farm. Nothing will settle like it should.” Alisha Risser, Lebanon County dairy producer: “We are proud of our milk that we produce on our farm, and we are proud of the Swiss Premium milk in our community. We are just asking the community to support us with letters to Dean Foods to provide a contract extension until fall or winter.”

Alisha Risser, Lebanon County dairy producer: “We are proud of our milk that we produce on our farm, and we are proud of the Swiss Premium milk in our community. We are just asking the community to support us with letters to Dean Foods to provide a contract extension until fall or winter.” Kirby Horst, Lebanon County dairy producer: “The thought of looking out at the pastures and not seeing the cows … I don’t know if I can handle that.”

Kirby Horst, Lebanon County dairy producer: “The thought of looking out at the pastures and not seeing the cows … I don’t know if I can handle that.” Dr. Bruce Keck, Annville-Cleona Veterinary Service: “Without a contract extension…This is like asking a loaded tractor trailer to turn as fast as a speeding car. It’s not enough time.”

Dr. Bruce Keck, Annville-Cleona Veterinary Service: “Without a contract extension…This is like asking a loaded tractor trailer to turn as fast as a speeding car. It’s not enough time.” Rick Stehr, R&J Consulting: “This is worth fighting for…worth fighting all together for.”

Rick Stehr, R&J Consulting: “This is worth fighting for…worth fighting all together for.”

Rep. Sue Helm: “A group of representatives are writing a letter Dean Foods. We want farmers to stay in contact with us.”

Rep. Sue Helm: “A group of representatives are writing a letter Dean Foods. We want farmers to stay in contact with us.” Rep. Russ Diamond: “We wanted to get Pennsylvania milk into Pennsylvania schools but have been told that with the product stream in Pennsylvania, this is hard to do. This Pa. Milk Marketing Board issue is a hard issue to get to the bottom, and people get very protective of it.”

Rep. Russ Diamond: “We wanted to get Pennsylvania milk into Pennsylvania schools but have been told that with the product stream in Pennsylvania, this is hard to do. This Pa. Milk Marketing Board issue is a hard issue to get to the bottom, and people get very protective of it.” Rep. Frank Ryan: “Keep faith first and foremost and your sense of humor and talk with your bankers. This is emotionally draining and people want to run from it. There is a solution and we need to work together to find it.”

Rep. Frank Ryan: “Keep faith first and foremost and your sense of humor and talk with your bankers. This is emotionally draining and people want to run from it. There is a solution and we need to work together to find it.”

Mike Eby, chairman National Dairy Producers Organization and former Lancaster County dairy farmer: “The media are our friends. We can work with the media to advertise our product in ways the (check off) promotion programs can’t.”

Mike Eby, chairman National Dairy Producers Organization and former Lancaster County dairy farmer: “The media are our friends. We can work with the media to advertise our product in ways the (check off) promotion programs can’t.”

“To be in this for the long haul, we have to look ahead and know what we’re dealing with,” he says, wistfully reflecting upon growing when his father made a good living with 40 registered dairy cows.

“To be in this for the long haul, we have to look ahead and know what we’re dealing with,” he says, wistfully reflecting upon growing when his father made a good living with 40 registered dairy cows. In fact, some farms are opting to sell quite a few heifers. Even though prices are not the best, these sales contribute to cash flow, which is critical. Some farms are breeding to beef breeds and producing a dairy beef cross for the feeder market. Again, not a big price, but the cost of the breeding is less, and the calves generate cash flow as well as cost savings. Such strategies require careful thought so as not to jeopardize the position of the herd for the future.

In fact, some farms are opting to sell quite a few heifers. Even though prices are not the best, these sales contribute to cash flow, which is critical. Some farms are breeding to beef breeds and producing a dairy beef cross for the feeder market. Again, not a big price, but the cost of the breeding is less, and the calves generate cash flow as well as cost savings. Such strategies require careful thought so as not to jeopardize the position of the herd for the future.